The 2002 Reform Law and Its Impact On Campaign Finance

The modern era of campaign finance law and spending began with the enactment of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) in 2002.

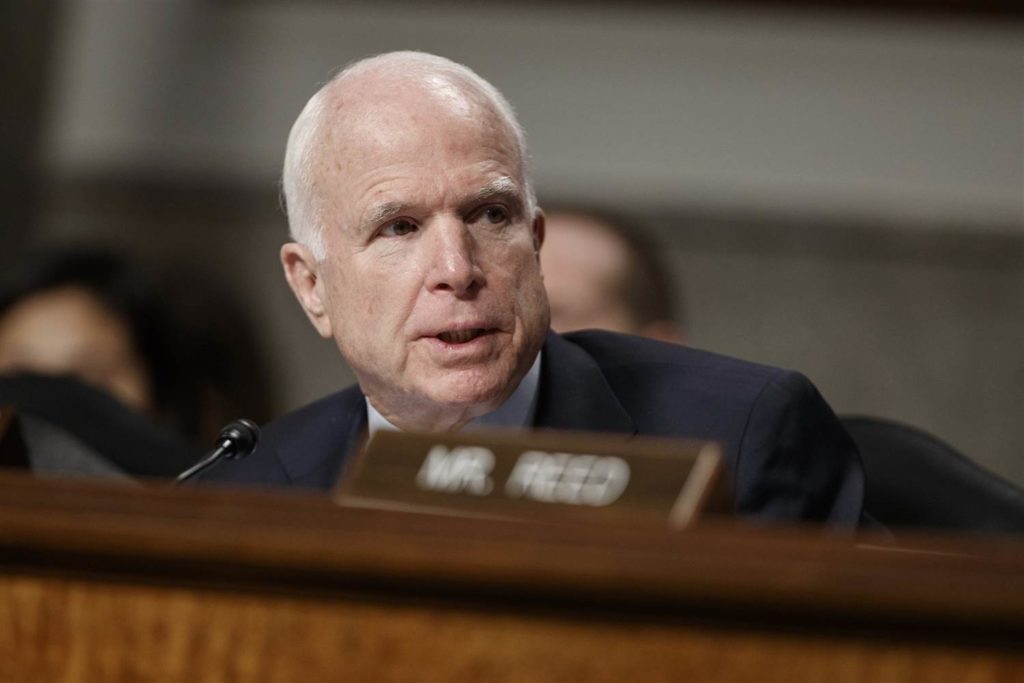

Known as McCain/Feingold after the bill’s sponsors, Senators John McCain and Russel Feingold, the law ushered in an era of independent group dominance of federal elections, and subsequently, state-wide and local elections.

BCRA, signed by President George W. Bush, served as the single most important reform of campaign finance law since Buckley v. Valeo in 1976.

The 2002 law came about in response to the uses of soft money by national political parties.

Soft money consisted of contributions to national political parties that were not subject to contribution limits. Wealthy donors could contribute any amount of money to the parties for supposed “party building” purposes.

As time passed, “party building” went beyond registration and get-out-the-vote to include, by the mid-1990s, generic issue ads that any discerning person understood to be in support or opposition to a candidate.

These issue-oriented ads easily evaded federal disclosure rules by leaving out obvious election-related wording like “vote for” or “vote against.” Buckley had ruled that disclosure requirements- at least in 1976- applied only to this type of express advocacy containing these “magic words.”

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act was enacted in part to restrict these issue ads that were unregulated but blended into electioneering communications. The law was intended to serve as an antidote to corruption and foreign money entering the nation’s politics.

Though well intentioned, the law would have unintended consequences. For one, BCRA served as an open invitation for independent, outside groups to enter the pantheon of national politics. And second, it ushered in an era of endless lawsuits and unsettled campaign finance law.

On the first point, BCRA set off an explosion of independent spending by prohibiting national political parties from receiving and spending unregulated soft money donations. Instead, donations to national political parties were now subject to contribution limits, making them “hard” money.

As a result, groups and individuals that used to write big checks to the national parties soon began spending heavily on their own in national elections. During the eight years after the law’s enactment, the independent campaign activity by these special interest factions increased over 1000 percent.

The Act disallowed corporations and unions from spending their money on issue advocacy or electioneering communications, though separate, segregated employee PACs could be established.

Further, BCRA restricted “electioneering communications” – issue ads that mention a candidate- within 30 days of a primary and 60 days of a general election but at the same time required broadcasters to sell time to candidates within 45 days of a primary and 60 days of a general election.

“If parties and groups want to run ‘issue ads’ during the 60-day period, they are free to do so, they merely cannot mention the name of a candidate. If they choose to mention a candidate’s name, they are still free to do so, but the expenditure must be disclosed and financed with funds raised under Federal election law,’’ said a 1997 press release by the late U.S. Senator and co-sponsor John McCain.

BCRA also contained a provision known as the millionaire’s provision. This provision allowed a tripling of contribution limits for candidates opposed by self-financed candidates whose expenditures exceeded the amount spent by their non self-financed opponents.

Many of BCRA’s main provisions came under attack and ushered in an era of endless lawsuits and unsettled campaign finance law, including McConnell v. FEC, FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, and Davis v. FEC.

Almost immediately after its enactment, Senator Mitch McConnell and a host of interest groups challenged the law. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case on an expedited basis.

With due haste, the Supreme Court, in December 2003, issued its decision in McConnell v. FEC, for the most part affirming BCRA. The court failed to rule on the millionaire’s amendment, contending that the plaintiffs lacked standing. However, in Davis v. FEC (2008), the Court would declare the provision unconstitutional.

In terms of “electioneering” and “issue advocacy” restrictions, the Court stated “nor are we persuaded . . . that the First Amendment erects a rigid barrier between express advocacy and so-called issue advocacy . . . Indeed, the unmistakable lesson from the record in this litigation is that Buckley’s magic-words requirement is functionally meaningless.”

As noted above, challenges to BCRA would not end with McConnell. In fact, in a series of cases, the Supreme Court would whittle away at the law until in 2010 when it would all but eviscerate it in Citizens United.

Citizens United is a nonprofit corporation, or PAC, founded in 1988. Prior to the 2008 presidential primaries, Citizens United released a documentary film entitled, Hillary: The Movie.

The film featured commentators, who in interviews, were critical of Hillary Clinton, a candidate in the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries.

The documentary was distributed to theaters and was made available on DVD. However, Citizens United desired to make the film accessible on video-on-demand within 30 days of the primary.

Under BCRA, corporations and unions were prohibited from using their funds for electioneering communications. FEC regulations construed an electioneering communication to be a communication that was distributed to the public.

Citizens United felt that its documentary might fall afoul of the law and therefore sought relief from the district court.

The nonprofit corporation maintained that the reform law’s restriction on independent expenditures was unconstitutional as applied to its documentary. It further alleged that disclaimer requirements were violative of the constitution.

In denying Citizens United its preliminary injunction, the federal District Court went further in granting the FEC’s request for summary judgment.

The District Court upheld disclaimer requirements and stated that BCRA was constitutional in relation to the movie as it was “susceptible of no other interpretation than to inform the electorate that Senator Clinton is unfit for office . . .”

Following the District Court’s ruling, the case was taken up by the Supreme Court.

In its most monumental campaign finance ruling in the 34 years since Buckley, the Court unleashed an explosion of independent group activity that has transformed the electoral system. BCRA lit the fuse that began the rapid growth of independent spending; Citizens United acted as accelerant.

The thrust of the case involved a reevaluation of Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990). The ruling in this case deviated from past precedent in upholding Congress’s authority to restrict corporate independent expenditures. In turn it also constituted a reconsideration of McConnell, which had adhered to Austin.

The rationale for Austin was based upon an anti-distortion standard, which involved the distorting effects of aggregations of wealth represented by corporations. The ruling in McConnell, on the other hand, was based more on two additional standards, government interest in preventing corruption and the appearance of corruption and a shareholder protection interest.

Buckley had connected the anti-corruption standard to upholding contribution limits but not expenditures. The shareholder standard had to do with protecting dissenting shareholders in corporations from being required to fund corporate political speech.

In making its ruling, the Supreme Court had to deal with two schools of precedent that were in conflict with each other; pre-Austin, which allowed independent spending by corporations and post-Austin, which did not.

In the end, the Supreme Court ruled that restrictions on corporate independent spending was unconstitutional as were the 30 and 60 days black-out periods before the election.

The Court did uphold the ban on direct contributions to candidates and parties by corporations as well as disclosure requirements.

In its decision, the High Tribunal stated, “The Court has subjected these requirements [disclaimer and disclosure] to ‘exacting scrutiny’ which requires a ‘substantial relation’ between the disclosure requirements and a “sufficiently important” governmental interest . . . The judgement is affirmed with regard to BCRA’s disclaimer and disclosure requirements.”

Without commenting on the merits of the Supreme Court’s position regarding the constitutional free speech rights of corporations, one thing is clear: the decision tilted the electoral landscape in favor of independent, often anonymous, groups and against traditional, fully transparent political parties and candidates.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.