After Floyd Killing, Grewal Aims for Legitimacy in Community Policing

When the killing of George Floyd rocked the nation, all eyes turned to the Minneapolis Police Department. Calls for reform to guard against police brutality and perceived systemic racism from police forces have led to protests of varying sizes and intensity. Around the country, many demonstrations have turned violent, with protestors clashing with police and paramilitary forces—as seen in Portland, Oregon—or with local police and local authorities joining in with the demonstrators peacefully but still passionately, as seen in big cities like Camden, to the smallest of boroughs such as Prospect Park.

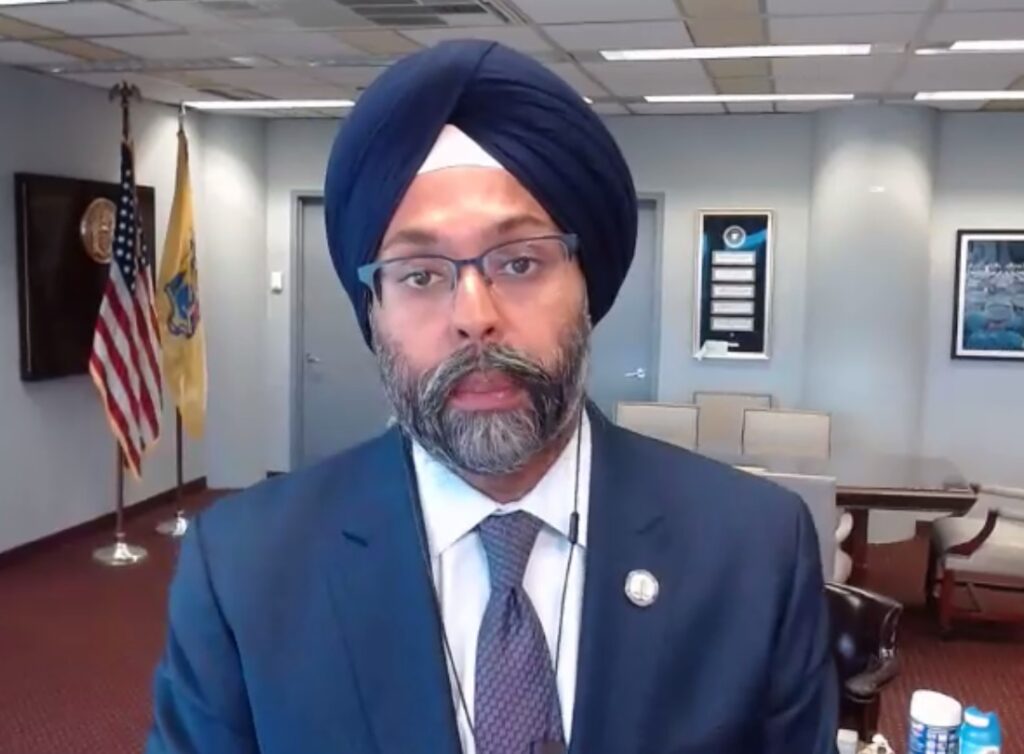

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal said he “saw murder on tape” with reference to the George Floyd video, showing the man pinned beneath the knee of Officer Derek Chauvin for nine minutes. As a consequence, attorneys general around the country have been looking at their states’ use of force policies to try to prevent such tragedies from recurring, rebuild trust with the community in general, and learn how to adopt the best practices for law enforcement.

Grewal hosted his second virtual Revision of Use of Force Policy video conference this week, hoping to gain input from the public and answer questions. The first conference had taken in so many questions that there simply wasn’t time to answer them, thus prompting the second conference. He was joined by three panelists: Jiles Ship, a commissioner of the New Jersey Police Training Commission and President of New Jersey NOBLE, National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives; Quovella Spruill, Director of Public Safety of the Township of Franklin, Executive VP of the NJ Chapter of NOBLE, former Chief of Detectives for the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office; and Jonathan Parham, Director of Police Policy Planning and Training at the Union County Prosecutor’s Office and former Police Chief of Linden.

“Back in June I announced that we were starting the process of revising our state’s use of force policy, which applies to 500+ police departments and 36,000+ law enforcement officers in our state,” Grewal said. “This is the first revision of this policy in over two decades and we’re absolutely committed to getting it right. And to get it right, we need robust community engagement and input.”

What followed was over an hour of questions-and-answers with the panelists, all of whom draw from extensive experience and who were, to their credit, willing to admit that mistakes happen and that policies are, in fact, in need of revision, as per the attorney general’s directive.

Questions from the public ranged from topics such as whether or not a person can file a complain against a police officer if that person feels he or she was targeted due to their race (they can) to what can be done about police culture which may suppress reporting bad cops. Many questions were related to the training of police officers and what new learning tools can be applied to better prepare officers for situations they may encounter in the field. The nature of many of the questions submitted, each carefully and methodically discussed by the panelists, suggested that one of the overriding concerns from the public was about trust.

As federal police are seen in places like Portland, with the president threatening to send them to other cities over the objections of state and local officials, escalation of tensions are broadcast continually on the news media and each day brings new stories of broken limbs, bodies disfigured by so-called “rubber bullets”, clouds of tear gas choking urban environments, marked journalists attacked by both police and protestors, and law enforcement eschewing the familiar and respected thin-blue-line for military-style uniforms and carrying military equipment, visually and psychologically blurring the lines between a domestic law enforcement situation and a legitimate combat zone.

When the mayor of an American city is gassed by federal police, with local police powerless to intervene, the message is that the use of force itself is unevenly applied and that leadership is fractured and thus cannot hold the complete confidence of the populace. In all, these things, whether or not they are technically legal, erode the public perception of the police as their protectors. That was something that Attorney General Grewal wanted to address and something his guests were all too conscious of.

On police accountability and internal policing, Ship said things had come a long way but there was still more to be done. “The majority of cops don't like bad cops because it tarnishes the badge of all the good cops who work day and night... frankly there aren't many chiefs who want a bad officer.” Ship added that, “Whatever mechanisms can be put in place through the Office of the Attorney General, we have to make sure that that officer who comes forward on bad policing is protected. It's critically important.” Ship emphasized the need to take these matters seriously. “One bad officer in the department can take over 20 years to regain the public trust. We can't deal with this in a Pollyanna way, we have to be swift and certain.”

“Police are supposed to be accountable to each other,” Spruill said, “but the culture says officers may be reluctant to do so, as they feel they might be the snitch or the rat and harassment may occur. It starts with the frontline supervisors. We have to require them to protect those officers who come to them with that information. It can prevent further abuse, corruption, misconduct, and inappropriate practices.”

Parham, a former chief himself, said, “Each law enforcement officer is responsible for doing the right thing.” With regard to academy training, Parham noted that socialization and conformity can and does lead to a degree of closed-mouth behavior. “We tell them to look like us, speak like us, act like us, there's a socialization process... it is inevitable that if they see something they won't want to tell on one of us. They don't want to get in trouble.” But that was something that supervisors needed to be conscious of and work against to protect the public as well as their own police departments.

One of Grewal’s more controversial initiatives put forward was to publish the names of officers who have had serious complaints or disciplinary issues made against them. Police unions have balked and pushed back, saying that the AG’s definitions are “too broad” but Grewal believes that this will incentivize department heads as well as officers themselves to avoid abusing their power or mistreating the public.

“If we put names attendant to these kind of reports,” Grewal said, “and year after year you see the same officer then members of the public can rightfully ask the chief why is this officer still employed with you? It's an added layer of accountability we believe will have a deterrent effect.”

Parham said he believed that the guidelines laid out by the OAG had a kind of “franchise” model effect, and that it would serve to eliminate any notion that there would be unfair or unevenly applied treatment within a department.

The subject of body cameras was discussed, with the panelists agreeing that while they are an expensive investment for a department, the unbiased evidence of visual recordings of a given situation eliminates the guesswork and he-said-she-said which can plague investigations of police-public interactions.

Ship noted that community relations improve when police have body cameras. And while they are expensive, he said, “so are lawsuits.”

When police and the public are being recorded, Spruill said, both tend to be on their better behavior. That can only be interpreted as a positive consequence. The body cameras also allow supervisors to review officers as they do their jobs and identify areas which need improvement before those problems manifest later on in greater ways.

Police resource reallocation, auditing, outsourcing of specific jobs to free up police talent within, and the subject of licensing to more “professionalize” the business of policing were all discussed in depth. But the fundamental basis of all those subjects was the matter of restoring and improving public trust. “Community policing is more than just ‘National Night Out’ or ‘Coffee with a Cop’,” Grewal said, “it's about building legitimacy.”