America’s Founders Remind Us that Transparency is Part of Civic Courage

In 2010, the Assembly Judiciary committee held a hearing on perhaps the first effort to legislate more public disclosure by independent groups that have since come to dominate New Jersey elections.

The hearing was held just months after the U.S. Supreme Court in Citizens United v FEC (2010) permitted unlimited independent spending in elections by corporations and unions.

During the hearing, during which I testified, a former member of the Assembly argued that anonymous speech was protected by the Constitution and by tradition.

The Assembly member opposed the pending legislation that would have required disclosure of contributions and expenditures by these so-called “outside” groups that engage in elections apart from candidates or parties.

The committee member cited the First Amendment as the provision in the Constitution that protected anonymous speech.

In fact, seminal cases including Citizens United and Buckley v Valeo (1976) have strongly defended the constitutionality of election-related disclosure. Federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have rarely overturned such laws if they are properly written.

When laws have been overturned, it hasn’t been because the Constitution gives absolute protection to anonymous speech.

Instead, it was because some laws in question did not meet the standard of “exact scrutiny,” critical in First Amendment cases, which means there must be a “substantial relation between the disclosure requirement and a sufficiently important governmental interest.” Others were not “narrowly tailored” toward election-related activity.

So anonymous speech is not guaranteed by the Constitution. However, laws requiring disclosure of financial activity by independent groups must meet key legal standards to avoid being struck down.

The claim that anonymous speech is protected by tradition is not accurate either. The Assembly member was right that the Federalist Papers were written anonymously.

But it was not because the framers believed anonymous speech was protected speech, that it was a Right, or that the authors feared retaliation.

Rather, it was because leaders of the American revolution, who were deeply versed in classical history, were inspired by the ancient uprising against Roman kings. They used their inspiration to rally Americans around their bold plan for self-governance.

Thomas Jefferson said in 1795 that “we have seen no instance of this (the American experiment) since the days of the Roman Republic.”

George Washington was often compared to Cincinnatus, the Roman farmer-turned-general who governed with integrity and relinquished his power voluntarily.

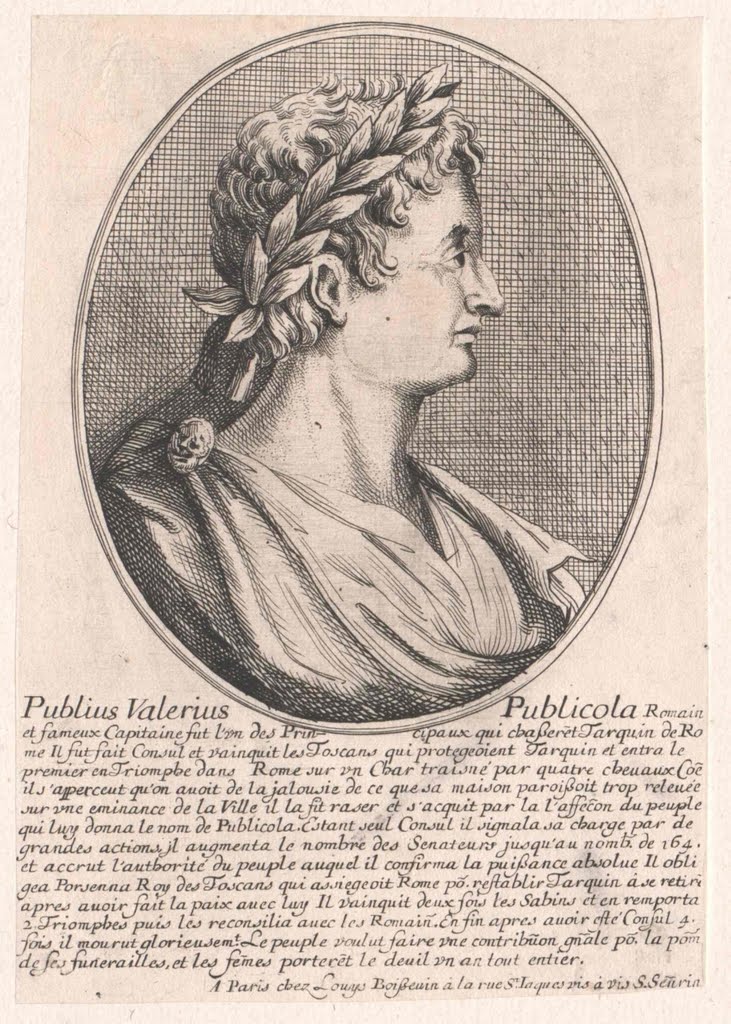

When the Federalist Papers were published, the authors used a pseudonym to align themselves with a famous Roman who challenged the Monarchy of the Caesars. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, the authors of the Federalist Papers, invoked the name of Publius rather than their own.

This pen name referred to Publius Valerius Publicola, one of four Roman aristocrats who in 509 B.C. established the Roman republic after overthrowing Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the seventh and last Roman king.

The founders were hugely influenced by the creation of the Roman Republic and hoped linking the two revolutions would inspire their fellow Americans as they distributed pamphlets, newspapers, and other written materials, and held meetings in coffee houses and taverns.

The Federalist Papers contain 85 essays meant to promote the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and provided a rationale for its framework. The essays were originally published in New York State newspapers urging ratification at a convention in that state.

The Federalist Papers were written between 1787 and 1788, five or six years after the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783.

There was no reason to fear retaliation by the British like there was in 1776, when 33 courageous men openly signed the Declaration of Independence during the war. Invoking the name of the Roman leader who helped bring down a powerful monarchy was intended to lend gravitas to the Federalist Papers essays.

Thirteen colonies turned into States when their delegates voted for independence at the 2nd Continental Congress. The colonies were in open rebellion against England. Therefore, so were the signatories who signed the document.

New Jersey delegates who put their lives, families, and fortunes in danger were Richard Stockton, John Witherspoon, Francis Hopkinson, John Hart, and Abraham Clark.

Today, open participants in our democracy include members of political parties, candidates, activists, and volunteers.

Yet, organizers of some independent groups have tried to operate in secret. Some of these groups have actively challenged efforts to require disclosure of their backers.

This is worrisome because outside groups spent over $50 million in New Jersey alone in 2021 seeking to influence legislative and gubernatorial elections. This spending outdistanced that spent by the parties and candidates.

Given the fast-growing clout of these groups, their opposition to expanded disclosure must be overcome. Otherwise, “dark money” is likely to eventually finance most election spending. Voters will have no clue who is trying to sway their votes.

In correspondence with Thomas Jefferson about the influence of wealthy aristocrats, John Adams once noted: “They not only exert all their own subtlety . . . but they employ the commonality to knock to pieces every plan and model that the most honest architects in legislation can invest to keep them within bounds.”

Adams comments are equally applicable to today’s aristocrats, particularly those who provide the funds for independent, anonymous groups.

It’s devilishly interesting to wonder what the response would be from signatories of the Declaration to the anonymity demanded by independent special interest groups which increasingly have an outsized influenced over election outcomes and the notion of government by the people.

The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia believed in regulating money in politics by making all participants accountable. He said, “Requiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed. For my part, I do not look forward to a society which, . . . campaigns anonymously . . . hidden from the public scrutiny and protected from the accountability of criticism. This does not resemble the Home of the Brave.”

It is time for independent, outside groups be made more accountable through disclosure of contributions and expenditures in the same way that New Jersey’s candidates and political parties are required to operate transparently under the state’s campaign finance law.

The Legislature and Governor can accomplish this and bring greater transparency and accountability to the State’s electoral system by enacting legislation that would require disclosure of election spending by independent, outside groups.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.