The Battle over $15 is a 1930's-like Defining Moment

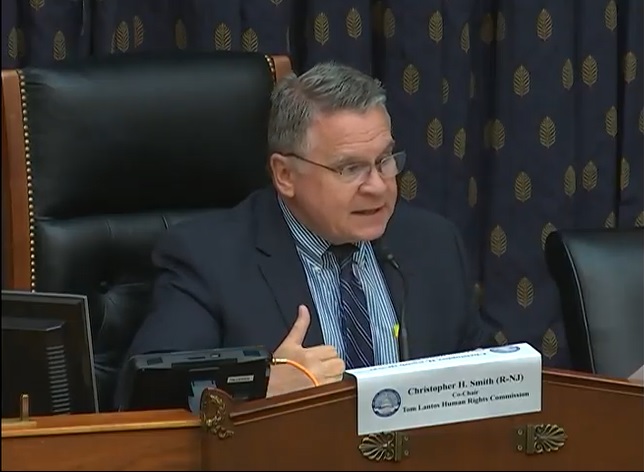

By a 219 to 212 party line vote in the House of Representatives early Saturday morning Democrats managed to pass President Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan with two party defections over solid GOP opposition including New Jersey’s Republicans Chris Smith (pictured, above) and Jeff Van Drew.

This coming week it will be up to Democrats in the U.S. Senate to decide the fate of the ARP’s most controversial provision, the first boost to the federal minimum in over a decade from $7.25 to $15.00 by 2025. Thanks to their solitary vote margin in that body the only pathway to passage of the Biden COVID relief package, without ten GOP defections, is through the byzantine budget reconciliation process which is presided over by the unelected Senate Parliamentarian.

The $171,315 a year Senate Parliamentarian has ruled that the long overdue hourly wage boost of $7.75 per hour for tens of millions of America’s lowest paid workers must be stripped out of the House bill because it does not comport with that body’s byzantine budget reconciliation rules which permits the majority party to pass such a massive budget bill on just an up and down simple majority vote.

THE OFFICE OF CIRCUMLOCUTION

I so lament that Charles Dickens is dead and unable to use his pen to describe this whole process by which overwhelmingly very wealthy Senators, who spent billions to get elected, hem and haw over providing a very time released boost to working people in the midst of a mass death event that has killed over a half-million Americans and infected 30 million more.

It’s so reminiscent of his Circumlocution Office, a parody of a 19th century British government bureaucracy in his 1857 novel “Little Dorritt” which, according to Encylopedia.com, was “run purely for the benefit of its incompetent and obstructive officials.”

It’s estimated that between 27 to 32 million Americans would benefit from the raise to the federal minimum which sets a floor for most, but certainly not all workers nickel and dimed in a gig economy where basic benefits like workers compensation, disability or even unemployment insurance are far from guaranteed while billionaires reap ever growing profits.

We know that the essential working families most likely to be uplifted will includes millions from the very same communities of color hardest hit by this pandemic whose members have died at more than twice the rate of whites who were more likely to be able to work from home remotely.

This push for the $15 minimum wage comes at a time when across the country millions of America’s essential workers, who do not have the option or luxury of working from home, put their health and that of their families on the line to keep the basics of our economy running. The initial talk of hazard pay for them has faded as polite society has come to hear the daily COVID body count like they hear the weather or Wall Street’s volume at the top and bottom of the hour.

AS POVERTY SPIKES

Even before the pandemic, the rate of American wealth concentration and acceleration after the 2017 Trump GOP $1.7 trillion tax cut was at breathtaking levels. Now, it’s ushered in a new American feudalism particularly evident in a high cost of living and racially segregated state like New Jersey where now in some counties more than one in three children are worried about their next meal.

Sylvia Allegretto, an economist at Berkley, University of California observed in December that in 2019, “the top 1 percent held one-third of all wealth. The next 9 percent controlled another 38 percent. Together they make up the Top 10 percent—a small group with a very large slice (71 percent) of the wealth pie. This left less than one-third (29 percent) to the bottom 90 percent.”

Allegretto’s analysis is based on 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data from the Federal Reserve Board.

Allegretto calculates that in 2019 the average family wealth was $748,800, while the was dramatically considerably less at $121,700. That upward sucking sound is the consequence of the top one percent’s wealth averaging $27.7 million—or 228 times the wealth of the median family. “The rich are getting relatively richer as this ratio—which stood at 125 in 1962—has steadily grown,” she writes.

Allegretto continues. “In early 2020, our response to the pandemic brought a halt to the longest economic expansion on record in the U.S. The COVID-driven recession continues to cause enormous pain and struggle for millions of workers and businesses. Nevertheless, as reported, for a few it has been a boom-economy on steroids.”

A KILLER RATIO

The Berkeley economist cross referenced the Federal Reserve data with the latest Forbes 400 list from 2019 and found that “the cumulative wealth of the richest Americans on the Forbes list 400 was $2.96 trillion last year. The wealth held by these 400 equated to the total wealth held by the entire bottom 58 percent of families in the U.S….It would take 2.5 million families all with the median wealth-holding of $121,700 to equal” that held by the eight individuals that topped the Forbes list.

Here in New Jersey, back in 2019 after Gov. Murphy signed the legislation which created a graduated path to a $15 an hour minimum wage by 2024, the Urban Institute, a non-partisan think tank, estimated it would raise the earning for 810,000 nondisabled workers who were citizens.

While both New York State and New Jersey have moved to get to that $15 minimum wage, 21 states, including our neighbor Pennsylvania, have not budged off that poverty level $7.25 federal minimum wage. To our south Delaware’s minimum is $9.25.

That regional disparity, informed by our borders, is a big deal for the hundreds of thousands of low wage essential worker families in the south and west of our state, according to the union that represents hospital laundry workers at the Unitex facility in Perth Amboy. They went on strike for two days in November to protest COVID working conditions and stalled contract talks. A union official said securing workplace protective measures for members gained urgency when three workers assigned to Unitex's Newburgh, N.Y. facility died of the virus.

"A new federal minimum wage of $15 is urgently needed for low-wage workers across the country, including in our neighboring states of Pennsylvania and Delaware,” said Megan Chambers, Co-Manager of the Laundry, Distribution and Food Service Joint Board (LDFS Union), Workers United/SEIU. “That's why we strongly support the current push to get it done in Congress. Essential workers, like the laundry workers and warehouse workers we represent, have sacrificed throughout this pandemic. They'll be getting to $15 here in New Jersey, but workers across the country need $15 to make ends meet. This is about a fair day's work for a fair day's pay. It's a matter of respect and human decency.”

NIGHT CREW EYE OPENER

For me the debate over the $15 minimum wage is not some public policy abstraction or exercise in trying to recall what it felt like to be working for the minimum as a teenager a half-century ago. Back in 2015, after getting let go from my job at CBS MoneyWatch, after a run in with the RNC spokesman Sean Spicer for a column I wrote about the hostile takeover of the GOP by Donald Trump, I started working the night crew at the ACME in Mt. Freedom for a few cents over $9 an hour.

It was a real eye opener.

The rest of the night crew were older guys closer to my age who had spent decades in their union jobs

and who over the arc of their long tenure had managed to get to a living wage and weeks of vacation. But they often had a hard time taking off that time because the post-Great Recession starting wage for new hires was a pathetic $9 for a job that was always just a few hours shy of what would constitute full-time, entitling you to health care coverage.

On break time we would complain about the pallets loaded 10 feet high by robots at the warehouse that we were convinced deliberately hid the heaviest inventory items in the load so that when we cut the plastic wrap that held the pallet load in place, we’d get crowned by flour of kitty litter.

Robots one—night crew zero.

HIDDEN FIGURES

In this mix of working-class supermarket humanity were retired folks whose pensions had been stolen by corporate raiders, grandparents raising their grandchildren and single working mothers who had to fret that a raise at their job at the deli counter would cause them to lose some benefit from the state like subsidized childcare.

And in their dilemma is what’s often missed in the conventional debate over raising the minimum wage when the GOP members of Congress like Smith and Van Drew say the $15 minimum wage is too expensive. What they fail to calculate is how corporations get away with paying low wages because we, the taxpayer, make up the difference for low wage families in form of food stamps, Medicaid and rental subsidies and don’t tax the super wealthy accordingly.

Earlier this month the Economic Policy Institute, a non-profit progressive think tank, calculated that a $15 minimum wage by 2025 would save between $13.4 billion to $31 billion in major public assistance programs. EPI estimates the current minimum wage is worth 17 percent than it was a decade ago.

“More concretely, full-times workers at the federal minimum wage earn $6,800 less per year in real wages compared with their counterparts five decades ago,” EPI found. “This has happened even as labor productivity has essentially doubled over the last 50 years. The amount of good that can be produced (or services that can be provided) in an hour of work has grown to twice what it was, yet workers’ pay has not.”

That’s the great American pyramid scheme that has working families always scrambling and government’s always borrowing, totally petrified the wealthy might leave.

THE POWER IN PRESENCE

Don’t fool yourself. America’s workers still have leverage if they have to courage to use it. As Sara Nelson, the charismatic leader of the CWA’s Association of Flight Attendants told me in an interview for the Chief-Leader back in November, the phrase "essential workers is basically like a 'please don't strike now' plea from the corporate elite because [they] have all the power."

Keep in mind, our state’s $12 minimum wage does not include so-called tip compensated workers, agricultural workers or the growing army of so-called independent contractors which can include anything from a nail salon worker to a TV camera operator.

For James Parrott, a labor economist with the New School’s Center for New York City, the fight for a $15 minimum was only one facet of a much broader battle workers are losing with the decreasing leverage of labor versus capital.

“Some of us [economists] thought in the wake of the pandemic there would some attention paid to the real precarity of low wage workers who lack a basic working safety net and are without unemployment insurance or workers compensation coverage—but there really hasn’t been a response to that at this point,” he told me on Sunday.