Beware the Ides of March

Most people, no matter what station they hail from, are concerned to some extent or another with their legacy. Have I been a good parent? Did I make a difference? Fundamentally, the question at its most basic level is, “How will I be remembered?”

The names of prominent mayors and business magnates may be immortalized on a plaque in town, on a marker stone, or perhaps across the façade of the public library, school, or university. A park might be dedicated to someone, others may have a statue erected. Public honors are a form of immortality and, perhaps, their great appeal. Few things are more frightening, especially to a public official who makes a career of being in the spotlight, than the idea of being completely and utterly forgotten. The public hopes that such recognitions are given to worthy individuals, but we are not so naive as to think that other factors would not contribute to honors in the public sphere.

Today, the 15th, is the Ides of March. In the church of the politico—whose temples are council chambers, state houses, Capitols, Parliaments, Kremlins, or palaces—those who have come to see themselves as deities in their own right should use today of all days to pause and reflect.

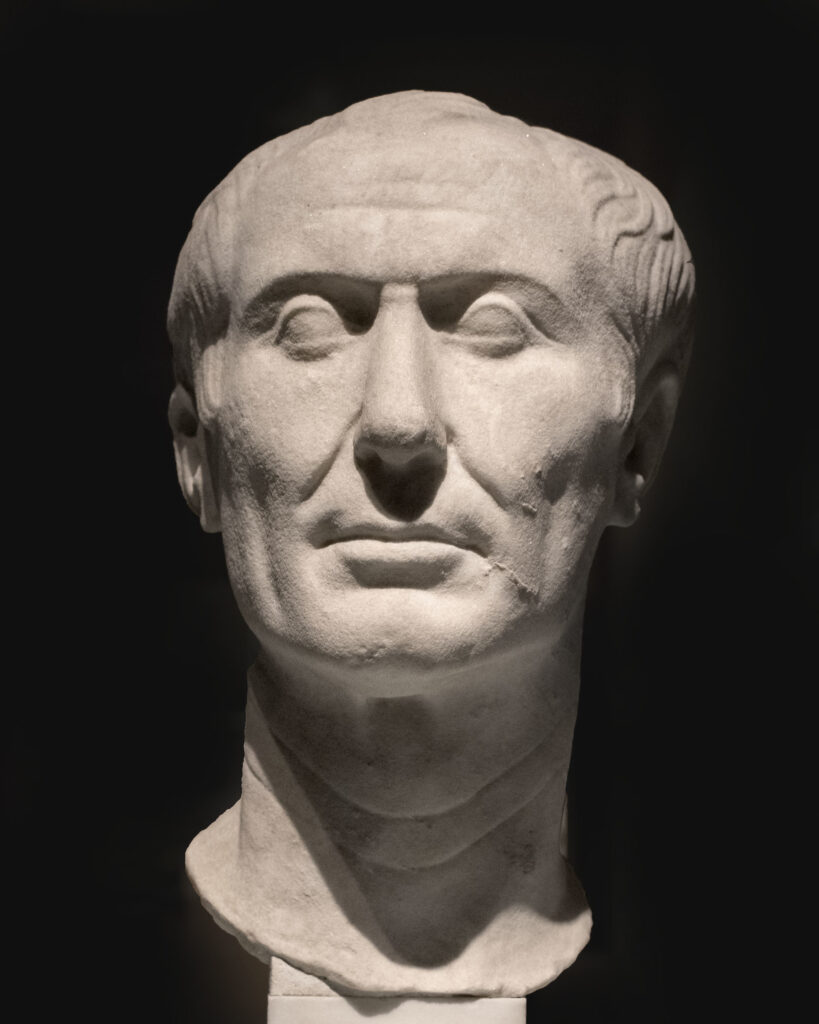

Without going into excessive detail about a subject familiar, or should be familiar, to anyone who wants to play a role in the public sphere, Gaius Julius Caesar was the populist consul of Rome and, for a time, her master. For those who skipped history class, Caesar, with an enormous fortune enjoyed fame and adoration from the commoners called the plebians. He had conquered the vast territory of Gaul (today’s France and Belgium) and brought back its loot, showcasing his triumphs publicly and deliberately. Caesar soon became the nominal ruler of the Roman Republic. But the Republic was a constitutional arrangement, too, where the deliberative body called the Senate was headed by two annually-elected consuls who, between them, held the executive power. It is important to note that Rome was originally a kingdom. It’s first legendary king and semi-mythical founder was Romulus, from whom Rome gets its name. The city was ruled over by various Etruscan kings in its formative centuries, until the last, Tarquin, through murder and terror, made himself an absolute autocrat, and instigated wars with neighboring Etruscan cities. This proved too much for the Romans to bear. The Romans overthrew the monarchy and established a Republic, where instead of one person with supreme power, there was a degree of power sharing among the ultra-elites of Roman society, the patricians, with an elected leadership. This was not democracy, but it was not autocracy, either, and a codified system of laws were in place to govern the new republic.

In times of emergency, Rome could appoint a legal dictator to serve for a fixed amount of time. During this period, the dictator had a free hand to do anything he deemed necessary for the preservation of the state. After the time expired, all his powers devolved back to the senate. This had happened a few times in Rome’s past and the Roman state endured. As Rome grew, so grew its political instabilities, crises, and upheavals. Rome could tolerate a dictator, but it would not have another king. Julius Caesar, consumed by self-confidence and believing his own propaganda, fatally miscalculated. He wanted to assume the office of an unprecedented Dictator-for-Life—a king in all but name. Claiming to be descended from the goddess Venus, Caesar was surely a kind of god-among-men. Had he not been among their greatest generals? Had he not distributed much of his wealth to the common man, earning their love? (Some would say buying it.) Had he not, through his relationship with Cleopatra, brought Egypt into the Roman World and used Egyptian grain to feed the hungry people of Italy? Had he not wowed the Roman people with his achievements?

A Roman general who had been awarded a Triumph by the Senate—a special military and religious parade in the city of Rome—would ride on a chariot, with his face painted in honor of Jupiter. Behind the general, a slave held a laurel over his head, whispering, “Remember, you are mortal.” This was, in effect, an institutional reality check. But for Caesar, one could see how he might have come to see himself as more than just a mere person. But a group of senators, wary of seeing their constitutional republic transform into the rubber-stamping apparatus of one strongman, proved his mortality to all the world in the form of dozens of stabs. Caesar died in the Curia of Pompey, which served at that time as the Roman senate house, named for his rival and fellow consul, the so-called Pompey the Great. All of his money, all of his glory, all of his carefully crafted imagery could not stop the bleeding.

In the end, the Republic was too far gone anyway. With the death of Caesar, civil war soon followed, and Caesar’s heir, Octavian, taking up his legacy, established himself as Rome’s First Citizen—a permanent consul who also held the powers of all other meaningful public officials. Elected consuls came and went, the pretense of the constitution was maintained, but the Republic existed only in name. The rest is history.

Before my wife and I were engaged, we had visited Rome and some other Italian cities for a short trip. She worked for a travel company and periodically their personnel would be sent to visit and assess the different tourist companies they set up clients with. We were lucky in that we had a private tour set up as part of her job to review—for me it was something of a vacation, and for a history and political science type, no place is better than Rome. When we toured the Forum in Rome, we found flowers left behind by visitors. Caesar, murdered in 44 BC, was still mourned some two-thousand-plus years later, our guide said. His legacy was secure, even if it was not without scrutiny.

Within the Forum itself, Benito Mussolini’s name can be found, for it was under his auspices that the city of Rome underwent extensive archeological excavations. Il Duce sought to capitalize on the grandeur of Italy’s Roman past and wanted to bring it back before their eyes. While Italy did have a reigning king, Mussolini envisioned himself as a new Caesar and by building upon the greatness of Rome, he would lead Italy out of its chaos and hardship into a future, strengthened by its past.

Such was his intent. But history demonstrated that strongmen, masters of the crowd (or the mob), were still just one individual riding the tidal waves of history. No matter how much power they held and however much they sought to control, legacy—perhaps the greatest prize—has always inhabited a realm just outside the grasp of the living hand.

The city of Rome is all about legacy. Legacy is found in every sight one can behold, whether the magnificent works of Michelangelo or the imposing Pantheon or the open space that marks the Circus Maximus or the triumphant Vittoriano or less grandiose markers denoting the resistance put up against the German occupiers in World War Two. Legacy itself is layered. Buildings on the surface hide an entire medieval and ancient city below, places people can visit and transition from the bustle of modern Italy’s capital city to the stony guardians of an almost three-thousand-year-old civilization. (In a very practical sense, it has impeded the development of a Roman subway system.) Rome is called the Eternal City, after all, and it isn’t so much because of the city itself, which is not the oldest of cities by a long shot, but for the immortality that its great names have gained.

It is worth remembering, especially among those who hold public office, that in death there is no defense against judgment. This has proven an especially hard concept for many Americans as we see the reassessment of our own figures from the past. Few things are as provocative as our own Civil War history. New Jersey, being a northern state, fought and fought hard to preserve our country from shattering and perpetuating the evil institution of slavery in the Confederacy. Thousands of New Jerseyans died and were maimed, both physically and mentally, fighting the South. Around the country, monuments to such figures had been erected, and after a solid century’s passing, many had also been taken down amid great controversy and outcry. Closer to home, some of our Founding Fathers, men who shaped the United States from the British colonies, have come under reexamination as well. How institutions have handled these varies. Some have said, let them be. Others have been relocated, some have been left as they are but with “contextualization,” while others have been erased. Some call this justice; others call it cancel culture.

“Do not speak ill of the dead,” is a common phrase, but it is also a common practice. A life can be spent trying to build up a legacy, or to provide an image that we want the world to remember us as—an image of our own construction, but no one is more vulnerable than the dead. The hero of today may be the villain of tomorrow. Sometimes the reverse is true. Evidence of wrongdoings whether criminal or personal, whether real or fabricated, could lead to the library being renamed, the bench being painted over, the statue being taken down. And there is nothing the formerly-honored can do about it. The surest bet of securing a legacy is a foundation of sincerity, truth, honesty, and benevolence. Perhaps happiest are those who can close their lives having reconciled that their legacy is out of their own hands, rather than try to coerce it, shape it, but ultimately try to build a castle out of sand. As Cyrano de Bergerac said:

I go caparisoned in gems unseen,Trailing white plumes of freedom, garlandedWith my good name—no figure of a man,But a soul clothed in shining armor…

However, such individuals seldom seek public office. Those who do deserve the credit and esteem of their peers, though they may turn from it. Those who do not, beware the Ides of March.

Leave a Reply