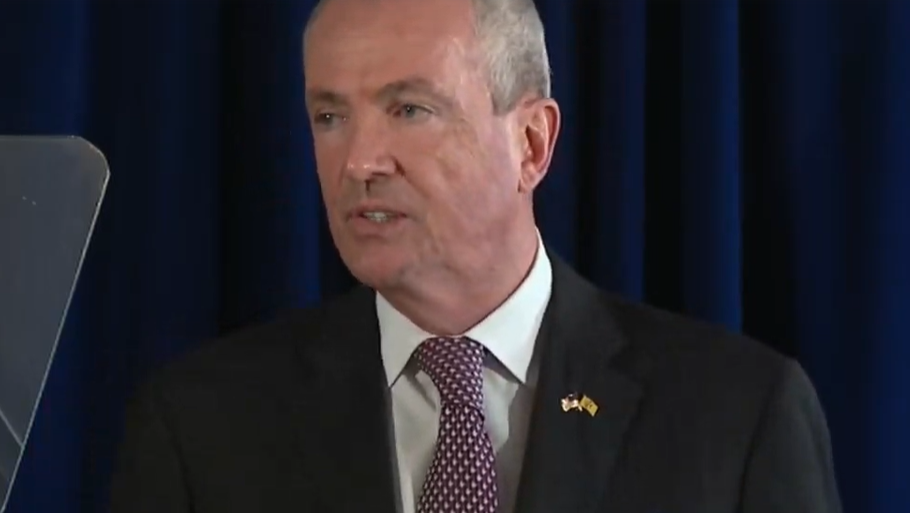

Requiring an NDA for Campaign Staff is Nonsense

Listen to audio version of this article

Ever since Kate Brennan, a Murphy for Governor campaign staffer, went public with her allegations that she’d been assaulted by a co-worker, only to see her complaint fall on deaf ears, speculation has swirled about the Administration that the campaign was beset by misbehavior and those who suffered under it have been prevented from speaking out in violation of non-disclosure agreements.

As a part of her lawsuit against the Administration, Brennan has asked the court to nullify the agreements, her attorneys claiming that at least five women were subjected to harassment or unwanted advances.

In attempting to explain requiring staffers to sign the agreements, a campaign attorney asserted it was necessary to prevent sharing information with outsiders.

Bluntly put, the rationale is so much butt-covering hogwash.

And, clinging stubbornly to the justification while stonewalling efforts to set aside the agreements stokes suspicions that they are intended to shield the campaign from tales of questionable behavior; what has come to be known as a toxic work environment.

The Administration attorneys have argued that the agreements are solely protective in nature and that lifting them could expose information concerning campaign practices and procedures never intended to become public record.

They are valid concerns --- up to a point.

Confidential, sensitive and proprietary campaign materials are closely held --- almost to the point of paranoia ---and access limited to top level staff.

Tactics, polling methodology and results, fund raising, advertising are all matters known fully to but a handful of individuals, a circle of advisers and managers in whom enormous trust is placed. They understand that in-house discussions of overall strategy remain just that --- in-house --- and that rigid adherence to that principle cannot be breached.

I served in a top position in three gubernatorial campaigns --- 1981, 1985 and 1993 --- and NDA documents were not mandated in any of them.

Requiring such agreements from paid as well as volunteer staff in the interest of protecting against deliberate or inadvertent disclosure to anyone outside the campaign is nonsense.

Those who show up every day to toil in behalf of their candidate are not privy to confidential material and, even if one stumbled across it inadvertently, wouldn’t be able to place it in any sort of intelligible context.

Volunteers, in particular, assume responsibilities ranging from answering telephones to stuffing envelopes to printing copies. A few are more intimately involved, but it is rare for someone in a non-paid capacity to take on duties involving confidential matters.

By their very nature, election campaigns are intense undertakings, bringing together people largely unfamiliar with one another and subjecting them to a pressure-filled environment for five months. Many are strong personalities with equally strong wills because the nature of the undertaking demands those qualities.

Tempers fray, frustrations boil over and arguments grow heated. Door-slamming is as common as expletive-filled rants, accompanied by physical assaults on inanimate objects --- chairs, telephones, books, pens, pencils and virtually anything else within reach.

To those who’ve never been exposed to it, the experience can be frightening.

The intensity grows in direct proportion to the stakes involved. A gubernatorial campaign, for instance, is a combination of sleep-deprivation, boring travel, lousy diet and the constant knowledge that a mistake --- an off-hand comment, a physical confrontation, flawed research or a missed opportunity to damage the opposition --- can be devastating.

Unsolicited advice from outsiders pours in from people eager to point out flaws and shortcomings in the campaign.

Former NFL football coach Bill Parcells, asked about the rigors of his job, replied: “Every Sunday, there’s 80,000 people sitting up there who can do it better than you can.” Campaigns are not much different.

The days are long and often the nights are even longer, punctuated by occasionally sticking around for last call at a bar whose name is forgotten when the sun comes up.

All things considered, profane outbursts can be understood and even forgiven in such an atmosphere. Harassment, belittling and berating co-workers, though, cannot. Comments or suggestions of after work personal liaisons are the strictest of taboos.

No matter the provocation, dumping anger and frustrations on subordinates or those who give of their time and energy to help a cause in which they believe is a sure sign of amateurish or insecure behavior. Professionals control their emotions, hold their tempers in check and focus on the task at hand. It is, quite simply, what they are supposed to do.

Leadership at the top is crucial if a campaign --- despite the pressures, stresses and strains --- is to succeed and all involved can share in the euphoria of victory.

In my career, I’ve been on the winning side and the losing side and when the election night party ends, there are hugs and apologies in equal measure.

The Murphy Administration has not dealt effectively with the non-disclosure issue, insisting that preserving campaign secrets takes precedence over public revelations of untoward conduct.

Maintaining a gag order --- fairly or legitimately --- nearly always produces accusations of hiding embarrassing incidents while delivering a message to women in particular they will not be permitted to come forward with tales of being ill-treated.

“What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas” may be a snappy tourism slogan, but “What happens in the campaign, stays in the campaign” is an affront.

Whether Brennan succeeds in her effort to lift the non-disclosure agreements or whether the Administration undergoes a change of heart and drops its opposition remains an open question.

It is, though, one more example of inexperienced individuals thrust into political territory new to them could be forced to act under public or legislative pressure.

It is not a good look for a governor who is fond of boasting about transparency and open book governing.

Carl Golden is a senior contributing analyst with the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton University.