The Flow and Ebb of Liberty–NJ’s Lost History of Voting Rights

Listen to audio version of this article

Over the July 4th weekend we will be inundated with the iconic images of our nation’s birth in 1776 that’s dominated by great white men memorialized in oil.

Throughout our school years we are taught that the history of our nation is a steady progression in pursuit of our Republic’s articulated promise of “liberty and justice for all.”

In this airbrushed history our nation is portrayed as ever broadening our definition of just what we mean by “all.”

Yet, a close examination of our state’s history reveals nothing could be farther from the truth and not knowing that means we don’t appreciate that there is nothing immutable about social progress nor our liberty.

Exhibit A: From 1776 until 1807, New Jersey women had the right to vote (and then lost it), more than a century before June 1919 when the U.S. Congress passed the 19th amendment which granted women the franchise.

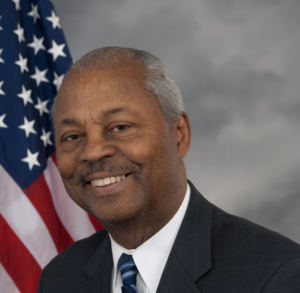

I first learned of this historical curiosity from the late Dr. Clement Price and Congressman Donald Payne

[caption id="attachment_59743" align="alignright" width="300"] Donald Payne, Sr.[/caption]

Donald Payne, Sr.[/caption]

(pictured) who both explained to me that our state’s radical experiment with universal suffrage included free African-Americans.

“…[T]he first New Jersey Constitution allowed women and free African Americans – as well as aliens and felons – to vote, whether deliberately or not,” writes historian Linda Garbaye.

In her comprehensive surveying of past historical accounts Garbaye notes that there is a school of thought that the 1776 iteration of the state constitution was a “mistake” yet she points out in laws passed in 1790 and 1797 lawmakers “clearly described women’s voting rights” leaving “no doubt concerning the legislators’ sympathies for women’s political participation.”

She continued, “Fourteen years after the 1776 New Jersey Constitution, in the New Jersey 1790 Election Law, the pronoun ‘she’ appeared for the first time, on the subject of voting qualifications, and thus included women in the electorate.”

Garbaye sites the 1790 election law adopted by the state’s 15th General Assembly: “All free inhabitants of this State of full age, and who are worth fifty pounds proclamation money clear estate in the same, and have resided within the county in which they claim a vote, for twelve months immediately preceding the election, shall be entitled to vote for all public officers which shall be elected by virtue of this act…”

Yet, she notes this legislation only included seven out of New Jersey’s thirteen counties that were in West Jersey where a “strong Quaker community resided, and a strongly Federalist part of the state. The Quakers are often perceived as having progressive views on some issues such as women’s political participation, pacifism, and the protection of rights of ethno-racial minorities.”

In 1797, the Legislature doubled down on inclusivity, electing to specifically include the pronouns “he” or “she” in their revisions to the state’s elections regulations, while extending suffrage for women throughout the state.

There did remain the requirement that a prospective voter be “worth fifty pounds, proclamation money, and have resided within the county in which they claim a vote” and “no person shall be entitled to vote in any other township or precinct, than that in which he or she doth actually reside at the time of the election.”

But by 1807 New Jersey’s radical experiment with more inclusive enfranchisement was ended when the charges of massive voter fraud surfaced. The remedy was restricting the right to free white men.

Ironically, it would be a New Jersey woman, whose education and world view was formed by deep and abiding Quaker influences, that would more than a century latter provide the breakthrough media and political strategy that forced former New Jersey Governor, then President Woodrow Wilson to shift from his “lukewarm” support of expanding the voting franchise to women to fully embracing it.

Alice Paul, who was born to Quaker parents in Mount Laurel, New Jersey in 1885, was the leading architect of the 1913 Women’s Procession that brought thousands of women to Washington D.C. in what was for the time an unprecedented protest.

A master of the media and the use of images to convey a political message, Paul led a persistent presence outside the White House in 1917 that the protestors maintained for 18 months. The disciplined cadre of women became known as the “silent sentinels” because they refused to be deterred by the near constant heckling to which they were subjected.

“In January 1917, Paul and over 1,000 “Silent Sentinels” began eighteen months of picketing the White House, standing at the gates with such signs as, ‘Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?’” according to the Alice Paul Institute’s webpage. “They endured verbal and physical attacks from spectators, which increased after the US entered World War I.”

The institute’s narrative continues, “Instead of protecting the women’s right to free speech and peaceful assembly, the police arrested them on the flimsy charge of obstructing traffic. Paul was sentenced to jail for seven months, where she organized a hunger strike in protest.”

“Doctors threatened to send Paul to an insane asylum and force-fed her, while newspaper accounts of her treatment garnered public sympathy and support for suffrage. By 1918, Wilson announced his support for suffrage.”

And yet, even as it seemed the tide was finally turning for women at the start of the 20th century, in 1907 Congress passed the Expatriation Act which decreed that any female American citizen who married a non-citizen lost their citizenship.

As a consequence, in 1920, thousands of American women, filled with the hope of finally getting a chance to exercise the franchise they had been so unjustly denied, found out that not only could they not vote but that they were no longer citizens.

And in this epic battle for women’s rights we hear the echoes of the very arguments advanced in our own time when the specter of ‘voter fraud and an immigrant invasion’ are used as a pretense for restricting ballot access through identification requirements and frequent purges of the voting rolls by usually white male incumbent elected officials looking to bullet proof their hold on their office.

No, this can be a stingy nation, where without the vigilance of the polity, our rights and privileges can be rescinded. Past freedoms are no guarantee of future liberty.