Happy Labor Day: Courts Back Casinos over Workers Hoping to Avoid Cancer

This Labor Day workers who hoped the state’s court system would end Trenton’s exemption for Atlantic City’s casinos from the state’s 2006 Smoke-Free Air Act that entitles workers to work in a smoke free environment were dealt a real disappointment by a judge who sided with the casino industry to keep the oppressively toxic exemption in place.

According to the U.S. Surgeon General, there is no safe level of second hand smoke which the American Cancer Society confirms contains at least 70 chemicals “known to cause cancer and trigger heart attacks, asthma attacks, and respiratory illness.”

The New York Times reported that in Judge Patrick J. Bartels ruling he asserted the state’s Smoke-Free Air Act did not “intrude upon a person’s right to pursue safety” under the state’s Constitution, because the exemption applied to only a “few industries.”

Bartels ruling is legal sophistry at its best serving the deep pocketed casino industry. Of course, the Casino Association of New Jersey praised the ruling that put the industry’s concern over their balance sheet over the well-being of the workers the industry relies on.

In New Jersey, history tells us, when it’s a close call it invariably goes to the same deep pocketed interests that rent the legislature and have an oversized influence on its courts as well as with our Governor.

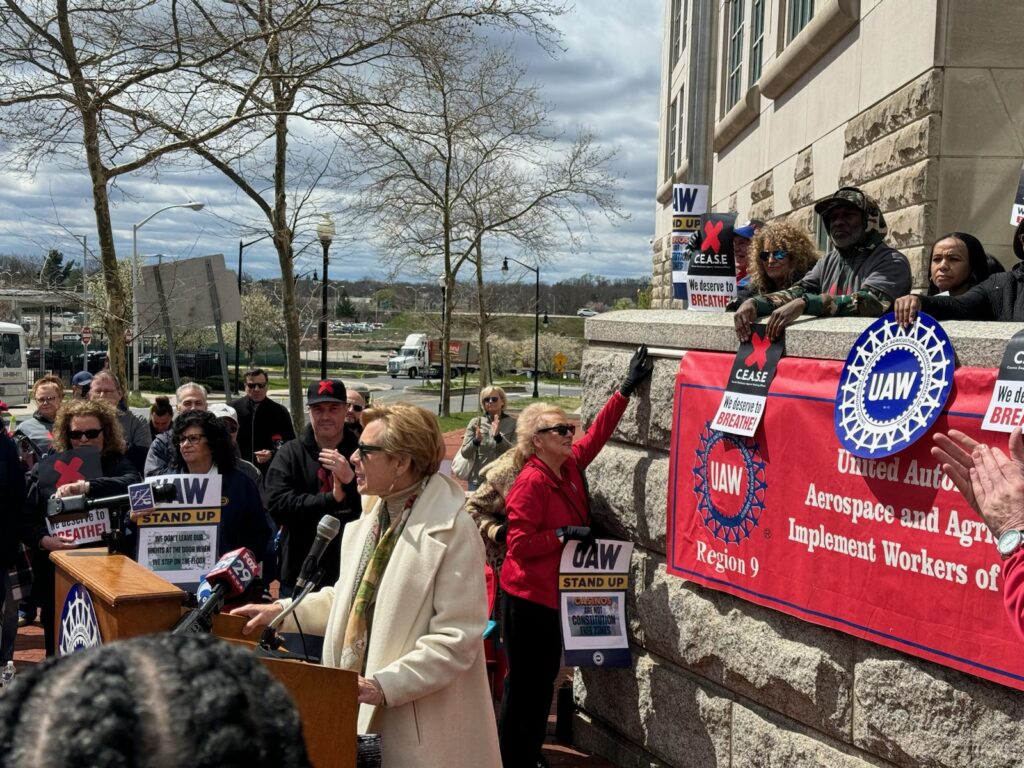

Back in April, scores of members of Region 9 of the United Auto Workers who work in the casinos and members of Casino Employees Against Smoking Effects, who work in non-union establishments, rallied outside a Trenton court on the occasion of their filing their law suit. On hand were some of the walking wounded who had contracted cancer from the casino second hand smoke.

Of course, missing were the casino workers whose exposure to workplace second hand smoke had already killed.

Nicole Vitola is a non-union dealer at Borgata and was one of the original members of CEASE that pressed for three years to try and get the legislature to lift the smoking exemption.

“With COVID, enough was enough — we had been suppressed for so long. I dealt with two pregnancies with smoke in my face — cigar smoke in the face,” said Vitola during an interview after the rally. “I was six months pregnant working with high-rollers and they allowed cigar smokers in the same small rooms with these high-rollers, and I still cry today when I think of how I put my kids in that situation because I needed benefits.”

Beverly Quinn, president of UAW Local 8888, is a blackjack dealer at the Tropicana. She told InsiderNJ at the rally that the COVID pandemic and Gov. Murphy’s temporality prohibiting smoking in the casinos was the turning point for casino workers.

“It brought awareness that people can stop and walk out to the boardwalk and smoke a cigarette and for two years we had no smoking in the casino and it really made us say we don’t have to put up with this,” Quinn said. “We have rights like every other person in New Jersey.”

“For casino executives, if you put on the uniform of a dealer, slot tech, bartender, server, maintenance person or housekeeper, the bosses are fine with you getting cancer and dying. It’s the cost of doing business,” said Daniel Vicente, Director of U.A.W Region 9, in a statement when the case was first filed. “The UAW will never be able to out-spend these executives, some making more than 10 million dollars a year. We can, however, take the fight for working people’s health and safety to a fairer playing field – one unbeholden to campaign donations or big money PACs.”

Nancy Erika Smith, counsel for the casino workers fighting the exemption, told the New York Times her clients would “appeal the ruling to the State Supreme Court on an expedited basis.”

“The workers exposed to toxic secondhand smoke every day are extremely disappointed in the judge’s decision siding with Governor Murphy, who chooses to endanger the health of casino employees in deference to the casino industry,” Smith told the newspaper.

Trenton has a long history of putting its thumb on the scale for mercantile concerns over public interest including its ever so slow ratification of the 13th amendment outlawing slavery until after the end of Civil War and after President Lincoln’s murder.

In their banter New Jersey’s great white men of the 19th century period expressed real concern for the slave owners bottom line. Our ruling elites were also keen to support creditors enforcing their terms with the full force of the law including jailing debtors no matter how small the debt.

As historian Peter J. Coleman notes in “Debtors and Creditors in America” the state saw itself as the essential enforcer for all creditors.

“By 1829 one New Jersey prison held five times as many debtors as criminals, and of the 117 prisoners in the Belvidere and Flemington prisons, about a quarter owed less than five dollars and more than half had been in custody for over thirty days,” Coleman writes.

“According to the Boston Prison Discipline Society, the incidence of imprisonment for debt was higher in New Jersey than in any other state, and prisoners were commonly held in ‘filthy and neglected conditions’ for the most trifling of debts.”

Into the 20th century, the State of New Jersey’s deep supplication to corporations caused Lincoln Steffens, one of the original muckrakers, to call us “the traitor state”.

While other states attempted to push back on the corrupting influence of big money that defined the Gilded Age and made anti-labor abuses of the Robber Barons possible, it was New Jersey that granted them legal safe harbor to avoid accountability through the proliferation of trusts much as we saw Judge Bartels deliver for the casinos.

“EVERY loyal citizen of the United States owes New Jersey a grudge,” wrote Stephens in McClure Magazine in 1905. “The state is corrupt; so are certain other states….But this state doubly betrays us…. Jersey has been bought and sold both at home and abroad; the state is owned and governed today by a syndicate representing capitalists of Newark, Philadelphia, New York, London, and Amsterdam.”

On the bright side, New Jersey is one of just 23 states that saw the percentage of employees in a union go up in 2023. According to the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Statistics, our state went from 16.1 in percent in 2022 to 17.3 percent of the workforce being in a union in 2023. While it’s not quite the robust spike we saw in Hawaii where union density went from 23.4 percent to 25.6 percent last year.

While there’s been a significant increase in union organizing activity it has yet to translate into an uptick in union density.

“In 2022, the share of workers who were unionized was 10.1 percent,” according to data reported by the Congressional Research Service. “This was a 23.4 percentage point decline from its post-World War II peak of 33.5 percent in 1954.”

Earlier this year, he U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) announced the cohort of workers represented by unions was 11.2 percent last year, down from 11.3 percent in 2022. As it turns out, there are real world consequences for this slippage over the decades.

“The decline of the American labor movement since the 1970s has been a major cause of stagnating wages and rising income inequality, and contributes to U.S. workers facing more dangerous working conditions than their counterparts in other wealthy countries,” according to the Economic Policy Institute. “ With the 2024 presidential election approaching, however, it is crucial to look beyond these economic consequences—as important as they are—and to recognize that the decline of American labor unions also leaves American democracy vulnerable.”

Casino operators argue that they provide a safe working environment and comply with health regulations.

Bud--are you aware that there is a bill to outlaw smoking in casinos SPONSORED BY DEMOCRATS? It's not them that is at fault. The casino lobby needs to be shut down.

I heard mar a Lago was pretty corrupted right after Bedminster?

Yes NJ is the most corrupt state and we keep voting in the same Democratic Party legislators every year. Term limits for all could help. Maybe try a republican led state government and see how long before they turn corrupt. And oh by the way Philadelphia is the most corrupt city in the nation followed by Chicago,San Francisco and of course D C

1965 - The Public Health Service established the National Clearinghouse for Smoking and Health which was later succeeded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Office on Smoking and Health. 1965 - The Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965 (79 Stat. 282*) required that the warning “Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health” be placed in small print on one of the side panels of each cigarette package. 1968 - The Office of the Surgeon General was abolished and the position became an advisor to the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. 1969 - Congress passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969 (84 Stat. 87) which imposed a ban on cigarette advertising on television and radio after September 30, 1970. 1973 - Arizona passed the first state law designating separate smoking areas in public places. 1986 - The Comprehensive Smokeless Tobacco and Health Education Act of 1986 (100 Stat. 30*) was passed to inform the public of any dangers to health resulting from the use of smokeless tobacco products. 1987 - The Office of the Surgeon General was reestablished. 1987 - An amendment to the Department of Transportation Appropriations Bill led to a smoking ban in 1988 on all domestic flights less than 2 hours, was extended to flights less than 6 hours in 1990, and to all domestic and international flights in 2000. 1992 - As mandated by the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act of 1969, the report "Smoking and Health in the Americas" was prepared to explore the historical, social, economic, and regulatory aspects of smoking in the Western Hemisphere. 1992 - EPA placed passive smoke on its list of major carcinogens. 2000 - California became the first state to ban smoking in restaurants and bars. 2019 - The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act was amended raising the federal minimum age for the sale of tobacco products from 18 to 21 years.

THIS IS THE REASON WHY I READ INSIDERNJ COLUMNS……To read columns like this! No, not because the columnists are handsome or beautiful. Perhaps sadly, at my age, I really don’t care. I read your column today, Bob Hennelly, because I know when I finish reading, I will be more knowledgeable. More importantly, I will, also, be more compassionate, more understanding, more enlightened. I waited in anticipation of your Labor Day Column You NEVER, NEVER disappoint. A sincere thank you for the labor you put into your Labor Day Column.