Independent Spending- What Goes Up Can Also Come Down

Independent, outside groups, often referred to as “Dark Money” groups, have been a very influential force in New Jersey elections in recent years.

But one development that could put the brakes on a two-decade-long trend toward increased independent group spending is a dwindling number of competitive congressional and legislative districts in the Garden State.

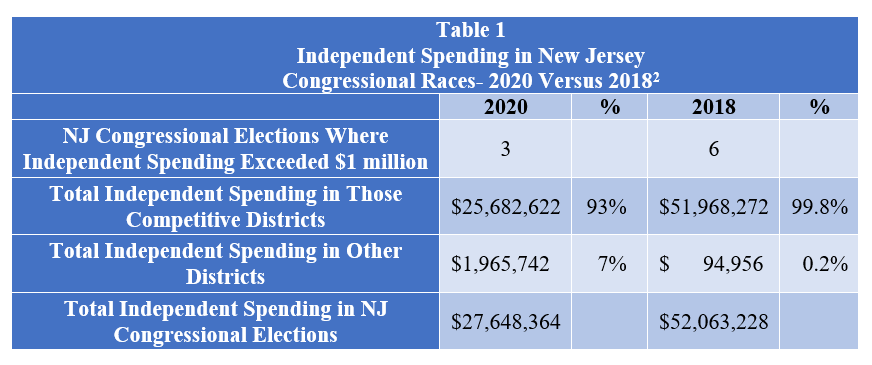

According to the Center for Responsive Politics, $27.6 million was spent by independent groups on New Jersey’s primary and general congressional races this year. This amount was $24 million less than the $52 million spent by these groups in 2018.

A very strong possibility exists that two years from now, independent spending will decline even more. All 12 New Jersey house members- ten Democrats and two Republicans- in 2022 will have been in office for at least two terms assuming they all decide to run for reelection. This will make them less vulnerable and their districts less competitive.

Michael Malbin, one of the nation’s top experts on campaign finance issues, has said one of the main goals of Super PACs and other independent spenders is to “win the close races.” Independent expenditure committees, he said, place “nearly exclusive focus on the most competitive races.”[1]

A comparison of 2020 and 2018 Congressional elections confirms that the trend toward less competitive districts in New Jersey- and a decline in independent spending- already seems to have begun.

In 2018, the US Senate race and five House district match-ups each drew more than $1 million in independent spending. At the top was the showdown between Senator Robert Menendez and Bob Hugin, which alone drew $21.6 million in outside spending. Menendez won reelection.

A total of $51.9 million- 99.8 percent of all the independent money spent in New Jersey in 2018- poured into those six campaigns.

[1] Malbin, Michael, “PACs in an Age of Super PACs,” March 6, 2013 presentation to National PAC conference. Malbin is executive director of the Campaign Finance Institute, which is now affiliated with the National Institute on Money in Politics. He also is a professor of political science at the University of Albany.

Seven other House races in 2018 drew less than $95,000 combined in outside spending. That signals they were relatively safe districts with bigger winning margins that would be hard for the opposing party to wrench loose even with outside spending.

In the 2020 elections, outside spending topped $1 million in just three districts.

The three districts alone attracted a total of $25.7 million- 93 percent of all independent spending. The second congressional district race where Rep. Jeff Van Drew won reelection was the biggest magnet, drawing about $13 million.

The other ten campaigns, including the US Senate race and contests for nine house seats, combined received just under $2 million in independent funds, or 7 percent.

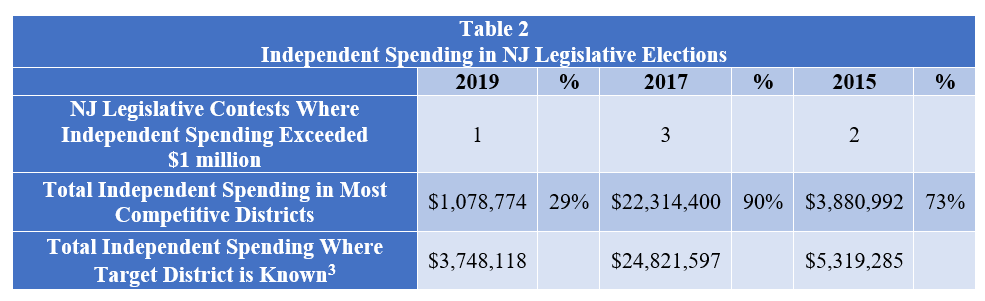

A similar pattern holds for recent legislative races. The slowing of outside group spending was seen in the Assembly election of 2019, when outside groups spent just $5.9 million compared with the $11.8 million spent by them in the Assembly election of 2015.

[1] Source: Center for Responsive Politics

The two most competitive districts in 2015 received a total of $3.9 million of independent spending- 73 percent of spending targeted by district.

In 2017, the third district state Senate race set a national record when nearly $19.8 million in independent spending poured into in to defend and attack Senate President Stephen Sweeney, who, in the end, won handily. Along with the two other top competitive districts, total spending was $22.3 million- 90 percent of known targeted spending.

In 2019, the most competitive legislative district received just $1.1 million.

No statistic better illustrates the two-decades-long growth in outside group spending better than the 11,458 percent spike in independent spending in New Jersey that took place between 2005-2017.

That suddenly changed in 2019, when independent spending on legislative races fell from an all-time peak of $27.3 million to $5.9 million- a drop of 78 percent.

Some of this can be explained by the fact that both houses were running in 2017 and it featured the most expensive state legislative race in US history.

But even if you just compare 2019 to 2015 since both were years when the only house up for reelection was the Assembly, spending was nearly half.

[1] Unlike Congressional races, not all independent spending in legislative races is broken out by district. Full independent spending totals by year were $5,856,004 in 2019, $27,290,174 in 2017 and $11,836,544 in 2015.

It could be that other races in the future could set new records for independent spending; perhaps a gubernatorial race in the future when no incumbent is running for reelection. Governor Phil Murphy already has set his re-election campaign in motion for next year.

When the governor first ran in 2017, it was a free-for-all that led to $24.5 million in independent spending- a record for a gubernatorial election. There were 16 candidates in the primary and general elections.

Again, competition increased outside spending.

The history of campaign financing has shown that patterns of spending and thereby changes to the electoral landscape often derived from changes to campaign finance law. However, this potential slowing of independent group activity may defy this historical tendency and derive instead from developments other than statutory reforms; in this case the disincentive for these groups to spend heavily in New Jersey due to the configuration of congressional and legislative districts that have become less competitive.

This does not mean independent groups, while exercising their right to participate under First Amendment speech and assembly provisions, should not be subject to regulation as are political parties. Nor does it mean that the party system in New Jersey should not be strengthened. It should.

As noted in previous columns, political parties are an integral part of the electoral and governmental systems. They make significant contributions to government, among them bringing compromise to the process, organizing government, and serving as a link between the citizens and their government.

Moreover, political parties are highly regulated under New Jersey laws, subject to disclosure, contribution limits, restrictions on their participation in gubernatorial elections, and guidelines in terms of how they should be organized.

Independent groups, under New Jersey statutes, are not subject to regulatory policy that even approximates that of political parties, though they similarly participate in electoral politics.

Only if they specifically support or oppose candidates, using magic words like “vote for” or “vote against,” are they required to disclose expenditures. They are not required to disclose contributions, which they can collect in unlimited amounts.

This column has prognosticated that independent group activity may be slowing down due to lack of competitiveness in congressional and legislative district races. Nevertheless, when engaging in election related activity independent groups should be subject to regulation similar to political parties. Moreover, political parties should be strengthened to bring balance to New Jersey’s electoral system.

This balance should not be left to natural causes. Instead, well thought out policies that strengthen parties along with requiring independent groups engaged in elections to disclose their activities will bring accountability and transparency to the process.

It will also engender greater trust on the part of the public in the state’s electoral process.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.