An InsiderNJ History of the 2018 Elections with Two Weeks and Change to Go

President Donald J. Trump overshadowed the cycle, according to New Jersey Democrats, even as they did their best to create enough drama away from that dominant and - they insisted - nefarious spectacle.

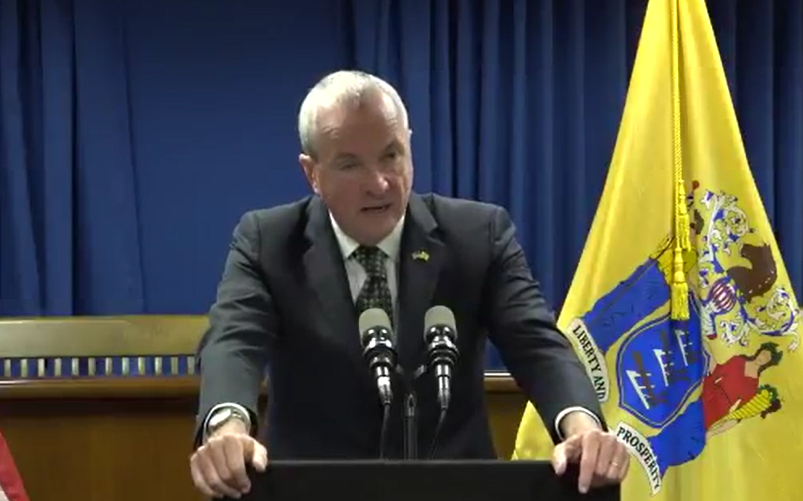

The congressional battlegrounds faded within the din of more persistent parochial drum beats, as Senate President Steve Sweeney (D-3) appeared, over the course of the last week, to have the momentum in his bid to weaken Governor Phil Murphy and turn a guy who on paper is the most powerful governor in the country into the governor in the country who wields the least power.

Sweeney looked pumped at Essex County Executive Joe DiVincenzo's party last Thursday night. He's

always thrived on herding cats, playing the role of the big working class guy in suspenders who thrives on a hundred simultaneous conversations. Like a foreman besieged in the bar after work hours, Sweeney stood in the Halloween glare of a roaring fire in McLoone's balancing the influx of Essex rank and file party members, almost as if he were playing a part bigger than senate president - like governor.

After the party, InsiderNJ spoke to an insider who had observed Sweeney regaling Joe D's guests.

"Doesn't Steve realize that if the governor's office opens up, George [Norcross] is just going to put his brother in there?" said the reveler.

It was his own opinion evidently, but he spoke it within the bigger framework of a bitter rivalry.

In self-preservation mode and eager to quash the potential for a meaningful primary, the Democratic Party establishment got behind Murphy in 2017 but remained leery of him, partly because his name wasn't Governor Chris Christie, but also because the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) later ran the most expense legislative race of all time against Sweeney and failed to budge him. There's a rumor in Trenton that Sweeney dropped out of the 2017 gubernatorial contest in exchange for Murphy agreeing not to run a senate president candidate against him. Then the NJEA ran against him. If it's true, it was like that scene in Scarface where Tony Montana tells Frank Lopez, "I'm not going to kill you, he's going to kill you," or least that's the way Sweeney's allies felt.

Not to mention Sweeney.

Having survived the NJEA, the senate president looked like the risen dead when he got back to Trenton.

More alive than ever.

But sore as hell.

That was the beginning of an ongoing war between Sweeney and Murphy, and it was a mismatch from the beginning.

A skillful leader of the senate schooled during the Christie years, Sweeney commanded a highly disciplined veteran SWAT Team-style staff on the inside, and relied on the political muscle of George Norcross III on the outside. The last budget season tested Sweeney's power. In a crisis, he had the ability to build a majority in his caucus, and the ready willingness of likeable Speaker Craig Coughlin (D-19) in the Assembly. Whenever Coughlin disagreed, he simply didn't attend Sweeney's press conferences and didn't protest - or wasn't around - when the senate president assured reporters, "Craig agrees with me on this."

The budget was a cruel testing ground. But South Jersey and their allies had wrested the speakership from Vincent Prieto when they wanted it and possessed the strength to check Murphy on the budget.

It was annoying to Murphy.

He had to compromise to suit the South. Had to monkey with the numbers on that millionaire's tax he wanted - just to suit Sweeney and GN3. The press handed Sweeney the budget game ball.

Oh, well.

Murphy still had a big, juicy target in Trump, who remained unpopular in New Jersey.

The Brett Kavanaugh hearings supplied the progressive governor with an excellent outrage amplification opportunity. When a woman stepped forward and charged Trump's pick for the Supreme Court with having sexually assaulted her in high school, Murphy led the charge here in New Jersey to condemn him.

"Kavanaugh ought to just pack up and leave town," the Governor told NJ.com.

Already feeling irrelevant, their best considered opinions on politics nullified by Trump's twitter feed, Republicans looked positively grim. And even though South Jersey-affiliated Democrats refused to attend the NJ Democratic State Committee bash thrown by Murphy and Democratic State Party Chairman John Currie (and featuring 2020 Presidential hopeful U.S. Senator Cory Booker), Murphy rode a 54-34% approval rating as he declared his hunger for Democrats to win not one or two more but all of the congressional seats in New Jersey.

Then a woman in the Murphy Administration publicly charged a fellow Murphy Administration official named Al Alvarez with raping her on the 2017 campaign trail, and said no one - including Murphy and his wife Tammy - did anything to help her, prior to Alvarez landing a $140K gig as chief of staff to the Schools Development Authority.

Then a woman in the Murphy Administration publicly charged a fellow Murphy Administration official named Al Alvarez with raping her on the 2017 campaign trail, and said no one - including Murphy and his wife Tammy - did anything to help her, prior to Alvarez landing a $140K gig as chief of staff to the Schools Development Authority.

The story sprawled Murphy.

If Alvarez had that kind of history on the campaign trail, and it was known, why had he received the state-level job?

If it wasn't true - and there were murmurs from one injured corner of what had been a fractured Murphy Campaign for Governor - why did Alvarez resign just prior to the Wall Street Journal story?

Murphy departed for a scheduled nine-day trip to Germany and Israel, leaving behind seemingly considerably fractured administration.

Chief of Staff Peter Cammarano and former Campaign Manager Brendan Gill didn't get along. Whatever goodwill Cammarano and Murphy Chief Counsel Matt Platkin had at the outset eroded fast, to the point where insiders said Murphy's inner circle contained a Cammarano faction and a Platkin faction. In the wake of the Brennan-Alvarez story, Cammarano and Platkin jousted behind the scenes as insiders laid odds on who between the two would survive.

A subsequent NorthJersey.com story about Derrick Greene getting $2 million during the Murphy Campaign for Governor sparked more questions.

It didn't help that Murphy - a big vision leader to this point with little demonstrable hands-on staff management skills - took the same advice he had for Kavanaugh and skipped town.

Facing the prospect of a suddenly roused Republican Party, nursing an already irritably anti-Murphy party establishment, and spurred by the obvious question of why Alvarez ended up in the administration with Brennan's charge hanging over him, Sweeney put together a select committee consisting of Senators Loretta Weinberg, Sandy Cunningham and M. Teresa Ruiz. On Friday, Speaker Craig Coughlin added Assemblywoman Eliana Pintor Marin to chair the assembly contingent of the committee.

As Democrats nationally fought to regain control of the U.S. House of Representatives from Trump, making those individual battleground congressional contests in CD2, CD3, Cd4, CD7, and CD11 especially urgent, and Menendez (saddled by his own almost unforgiving storyline but afloat, according to the polls) tried to withstand multi-million dollar Republican challenger Bob Hugin, Sweeney v. Murphy reclaimed the mantle of dominant New Jersey rivalry.

Trump was doing a fundraiser for Assemblyman Jay Webber (R-11) in that North Jersey battleground, which Democratic candidate Mikie Sherrill said would be close, no matter what the polls said. "They must see something in there in the 11th," on source told InsiderNJ. "Isn't that [New Jersey GOP operative-turned White House political adviser Bill] Stepien?"

Trump and his allies had battled with U.S. Rep. Leonard Lance (R-7), who bucked and infuriated the president when he didn't ultimately vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The White House at the time even invited a potential Lance challenger in the GOP Primary, Craig Heard, down to D.C. for talks. Heard didn't end up running, but Trump had made the point.

Trump and his allies had battled with U.S. Rep. Leonard Lance (R-7), who bucked and infuriated the president when he didn't ultimately vote to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The White House at the time even invited a potential Lance challenger in the GOP Primary, Craig Heard, down to D.C. for talks. Heard didn't end up running, but Trump had made the point.

Anyway, Lance was running away from Trump.

Or at least trying to have it both ways.

Let him, and his Millicent Fenwick-shaped allies - the former Governor Christie Todd Whitman's and state Senator Kip Bateman's of the world, both of whom had backed Ohio Governor John Kasich once Christie exited the 2016 presidential race - twist.

Let Lance fend for himself against Democratic challenger Tom Malinowski, who appeared to be running a strong ground game in the closing days of the campaign season. If Menendez was supposed to slow Malinowski in the 7th, the candidate appeared not to be allowing outside interference to inhibit his progress against the incumbent. He had visible operations where Democrats ordinarily didn't look strong, in places like New Providence, Westfield, Mountainside, Hillsborough, Bridgewater, and Montgomery. And he had money.

Unlike his more cautious CD-7 Republican counterpart, Webber was stout in his comments about the president, welcoming his support when Trump first tweeted his commitment to the CD-11 Republican.

As for CD-3, GOP-dominant Ocean looked secure in its Trump love. And Burlington County Democratic Committee Chairman Joe Andl had kneecapped his party when he selected a countywide candidate - George Youngkin - who turned out to have been named in a string of harassment cases.

If the president was going to swoop in make a statement in New Jersey, it was going to be CD-11.

Plus, Webber needed the money. Self-funder U.S. Rep. Tom MacArthur (R-3) didn't.

The polls showed a close contest, but MacArthur, the White House must have calculated, could take care of challenger Andy Kim.

Post election, Democrats would handle Andl.

They were good at that, New Jersey Democrats, the White House had to conclude, dividing and conquering themselves when it counted. It showed in the confusion caused by Menendez at the top of the ticket in some of those key congressional battleground districts. It was the ages old party anathema that progressives had for machine politicians.

Menendez was the ultimate machine guy.

The newcomers to the battlegrounds weren't.

The machines, such as they were in CD-7, for example, had in fact mostly gone in another direction from Malinowski during the primary.

It didn't seem to bother him.

He and Menendez were different.

Just as Sweeney had crafted his political career in the party machine, and Murphy hadn't.

As for CD2, that was already over.

State Senator Jeff Van Drew (D-1) was going to beat Republican attorney Seth Grossman.

No need to get mired there, the GOP had to figure.

South Jersey Democrats' play for a congressional seat was secure.

Except for Camden, the Republican-leaning counties down south wouldn't go for Menendez, a source noted.

So - with Van Drew in cruise control in a district currently occupied by U.S. Rep. Frank LoBiondo (R-2) - the South's campaigns and elections work was essentially done.

Thus, with Sweeney and Murphy newly embroiled, Hugin doing enough to appear competitive against Menendez without wanting to impair himself statewide with the president's presence, and those other congressional battlegrounds accounted for, Trump jumped into the bloody trench of CD-11 with Webber, who persistently complained about Sherrill sharing the same party affiliation as Menendez, hitting her in that easy-to-fracture area with time running down.

Everyone had their preferred rivalries, or found themselves stuck to them despite their best efforts to escape them.

Insulated by nearly a million more registered Dem voters than Republicans on their side, NJ Democrats would always have themselves to kick around.

So Webber jabbed at Menendez-Sherrill, Sherrill-Menendez, and - in the face of what Democrats said was a coming wave of voters who didn't finally care about those insider egos and their nursed hurts - rolled the dice in a Republican district by bearhugging Trump.