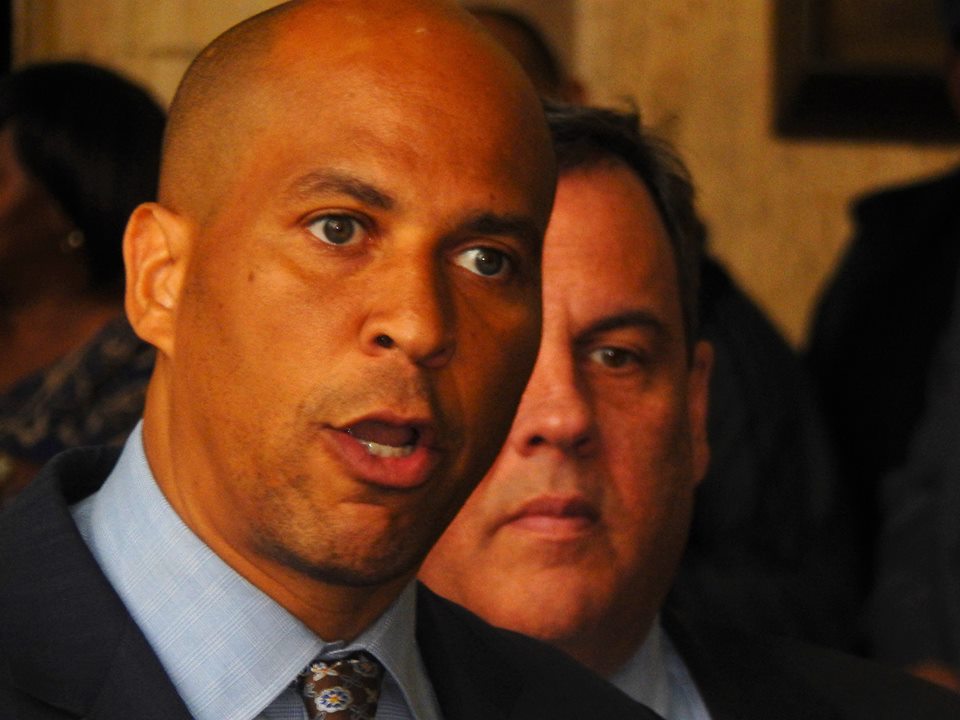

How NJ's Cory Booker and Chris Christie Take Two Fundamentally Different Strategies for Presidential Campaigns

Listen to audio version of this article

Here we are, New Jersey, confronted with the ash heap of our common, bumper-to-bumper quality of life while yet another politician stands atop the ruins proclaiming his absolute conviction that the country should pay attention. In 2016 it was Republican former Governor Chris Christie who made the case for himself to take the reins of the American buckboard, and yesterday, with his sights on 2020, U.S. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) formally entered the contest.

A Romulus and Remus story for a state that never quite reached the ankles of ancient Rome, Booker and Christie enjoyed common political antecedents, including a donor pool of many of the same entities and powerful individuals, some of them tied to the charter school movement. There's also this. But they also have a fundamentally different starting point with which to engage the voting public.

Whatever the overlapping New Jersey narratives of their twin political destinies, each worshiped and worships fundamentally at a different altar.

Family-centered in his public narrations, Christie, for his part, more than toyed with the concept of respect, while Booker, intent on making Martin Luther King, Jr. inspiration the focal point of his kickoff speech at Military Park in Newark yesterday, relentlessly underscored love.

They're different.

How Chris Christie Focused on Respect

As a public man, Christie tip-toed around love, ever cautious about letting his guard down long enough to transmit a sense that any kind of affection might be heretically misconstrued as, not only namaste or "bowing to the divine in you," but something else.

Unless he was discussing the strictest definition of family, Christie squirmed with the very concept.

That said, love was not completely out of the question.

It was buried, but left visible.

Running for president, the former two-term Republican governor exhaustively footnoted his late mother when describing his preferred approach. "She said, 'if people respect you, love will come,'" Christie intoned.

He wasn't interested in building the foundation of his campaign on love. He would craft it out of respect, and if he won people over that way, as a tough-talking, frank and quick-to-anger individual, maybe he would break them down piece by piece until they eventually felt like curling up with him beside the roaring fire of life.

Then he could tell them, "f-k" you.

Booker doesn't approach public life that way.

Cory Booker's Message Centers on Love

He starts by claiming to love the other, appearing not to care if people disrespect him or ridicule his effort to appeal to the human family.

He appears to heavily borrow from Jesus, insisting, if he's slapped, on turning the other cheek.

Family for Christie means the other people you see when you lock and bolt the door.

Booker believes that, too, but he also appears intent on recognizing the inter-connection of people as a form of family.

And they're there to be loved, not given the middle finger at the first opportunity.

If a feeling of being unloved in return becomes too irritating, he can always have "some kid" who runs twitter quietly remove a nettlesome critic, or gently complain to the media about an unfavorable story, or have a subordinate pick up the phone and do it for him.

But in the main, love is the John Lennon-like bird seed he wants the American public to nibble out of his hand.

Now, as he embarks on a presidential run over the vanquished remains of his New Jersey predecessor, the question is whether President Donald J. Trump better understands what Stokley Carmichael vainly tried to tell Martin Luther King, Jr: namely that politics is simply power; while (Christie might say) Booker has little to work with by tapping MLK's higher order of thinking when his audience is akin to a World Wrestling Federation (WWF) event.

Christie's philosophical foundation didn't lose 2016.

Christie's Approach Worked

It won, in fact.

It won big, bigger than Christie could embody, as Trump molded his own mystique built on the same principle of punching the weakest man onstage if it meant an easy applause line.

It's elemental.

Men in this culture fear losing respect.

In their bones, they tremble with a sense of the loss of that huge leg up they once received as a birthright of gender. At their worst, Christie's seemingly endless collisions with other people transmit less a sense of modern day Caesar on horseback and more the image of a man unsteady and out of control, a majestic sense of self under siege and threatened by the world around him. That encounter on the boardwalk where he attempted to walk down a supposed-schlemiel with an ice cream cone in his hand underscored the absurdity of modern man's effort to impose his most inflated Napoleonic sense of self on his surroundings. The crude impulse that convinces us of having to express dominance through violence, our eagerness to threaten violence, or flare anger, merely advertises our dislocation from the world. Our own unsettled inner lives makes it easier to lash out sooner than restore those insecurities.

They show weakness in the real world; but in the subtly uncivilized world of politics, they offer the thin possibility of an advantage in a theater of sameness and colorlessness supplied by too much restraint.

In his lead up to his presidential announcement amid ongoing criticisms of Barack Obama as too zen-like to understand the angst of every man, Christie spoke of his sense out there in society of real anxiety. Obama's apparent decision to evolve out of visible anger always put him at risk politically of appearing emotionally disengaged, giving Christie and Trump a chance to ratchet the anger and anxiety that usually results in someone kicking over a television set. The fading male attempts to soothe his fellows with a sense that the siren song of violence is so intense, his ignorance of being able to differentiate agape from philia, so complete, that it is perhaps best (or only) fortified by his deepened sense of philatuia, or self love as an organizing principle for facing a devitalized world.

Booker is gambling.

Booker is Taking a Riskier Approach

Most males detest the concept of public love (check out liberal prez candidate Eugene McCarthy in 1968, mortified about the pain of having to express his feelings in public) because viscerally it challenges their self-imposed structure of power. Why evolve if the power structure as it exists sustains males as they have existed?

If Christie felt the male angst sufficiently to risk appearing out of control, and Obama felt it sufficiently to remain unmoved, for risk of looking like a fool, Booker - faced with a blown-up Christie-like incumbent president tapping into the male fear of love - risks the ultimate challenging organizing foundation for his campaign for half the voting population. It may be too challenging a concept for those who believe the only way to defeat the Three stooges-production president is to beat him on his own terms in a Ringling Brothers-like clown crack-up.

Booker and Christie for the most part had a symbiotic political relationship in New Jersey. But if Booker zigzags through the crowded field into contention with Trump, it will be the New Jersey governor's contest that never happened, with Trump, admittedly even more theatrical than the always excitable Christie but at his core philosophically consistent, subbing for the former New Jersey governor on a presidential stage.

All of it is far from Crystal City, where former U.S. Senator Bill Bradley (D-NJ), a Booker mentor, kicked off his own doomed candidacy for the presidency in 2000, talking about firing a .22 rifle down by the river, listening to a family member confessing to never foreclosing on a single home during the Great Depression, and speaking not of love or respect but "shared sacrifice" as the organizing principle he learned as a basketball player salvaged for his campaign. "Giving up something small for yourself in order to gain something large for everybody," said Bradley, far from New Jersey, in the former politician's home state of Missouri, and from the present day.

Spartacus is a big YAWN. Nothing to see here. Keep moving. Hypocritical phony!