The Moveable Feast of David Friedland

The author Ernest Hemingway described his years as an ex-pat in Paris in the 1920’s as “a moveable feast,” a life teeming with fascinating personalities and experiences that left an indelible imprint on the human memory.

For those who’ve spent significant parts of their lives as a participant in or an observer of New Jersey politics, Hemingway’s characterization holds resonance.

It is a permanent reservation for a seat on the aisle to witness or even influence events while exposed daily to individuals of dazzling intellect as well as those of lesser abilities, to view drama as well as farce, and to become entranced to the point of addiction.

In the twenty-five years I spent on the Legislature’s staff as well as the governor’s office, no one I encountered embodied the qualities of which legends are forged--- for good or ill --- more than David Friedland who represented a Hudson County district in the Legislature from 1966 to 1980.

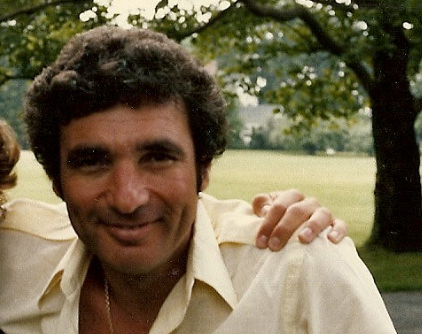

In a county and a state with colorful and rich histories of scoundrels and rogues who populated the political universe exploiting their public positions for private gain, Friedland achieved notoriety, cutting a dashing figure attired in custom tailored suits strolling the corridors of the State House.

David died this past week at age 84, mostly forgotten by today’s political cognoscenti unaware of the larger than life dominance he exerted in the 70’s and 80’s from his central role in changing New Jersey’s political landscape forever and for the better to his association with the dark side of organized crime and corruption to his James Bond-like adventure to escape Federal incarceration.

Prison will do that, scrubbing history clean and transforming vivid memories into foggy and quickly dismissed mental images.

I met David in 1971 when I joined the Assembly Republican staff after a four-year stint in a congressional office in Washington, D.C.

He was a force of nature, articulate leader of the Democratic minority who achieved a reputation as someone who could change votes with the force and persuasion of his arguments.

His serious side was balanced by the impish, though. He once demanded the Federal government place the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor on a swivel because her rear end pointed at Jersey City, a situation he found an affront to his constituents in particular and the state in general.

In one particularly contentious debate on the Assembly floor, he lambasted the bill under consideration with pointed insightful criticisms, pausing only when an aide whispered there was an urgent telephone call for him.

Upon his return some 15 minutes later, he took the floor again and announced: “Now that I’ve given you all the reasons to vote against this bill, let me give you all the reasons to vote for it.”

The telephone call it turned out was from the Hudson County political leadership who reminded him they supported the bill.

It was Friedland, though, who changed the state’s political landscape forever when, in 1964, he mounted a successful court challenge to the New Jersey’s legislative representation system, arguing that providing each county one Senator violated the “one man, one vote” provision of the U. S. Constitution which required legislative districts of approximately equal population.

Cape May County, for instance, with a population a fraction of that of counties such as Essex, Hudson, Bergen, et. al., would no longer possess equal weight in legislative representation.

In 1967, the election was conducted in newly drawn Constitutional districts, bringing balance and fairness to a system which up to that time had neither.

He is best remembered, though, for breaking a partisan deadlock in the Assembly following the 1971 election which resulted in 40 Democrats, 39 Republicans and one independent taking office, denying both parties the 41 votes necessary for control.

Friedland recruited three Democratic colleagues to join him in crossing over party lines and delivered four votes in support of Essex County Republican Tom Kean for Assembly Speaker.

The ensuing partisan and media outrage that erupted positioned Friedland where he most enjoyed it --- the center of controversy and attention. He defended his defection as in the best interests of Hudson County which he argued had been ignored by Democrats for years.

The uproar quieted, Kean went on to become a highly effective Speaker, Friedland reveled in his role as kingmaker, and I spent two years as press secretary for the Assembly leadership.

His fall from grace began in 1979 when he and his father, also an attorney, were indicted by a Federal grand jury. Both were convicted in 1980 of bribery for their role in securing a loan from a Teamsters union pension fund as well as income tax evasion and obstruction of justice. Friedland, who’d been elected to the Senate in 1977, resigned.

In 1982, in return for avoiding prison he agreed to cooperate with Federal authorities to provide information which led to indictments and convictions.

In 1985, while awaiting sentencing, Friedland engineered the most audacious escapade of his career, faking a drowning at sea while scuba diving off the Grand Bahamas.

It was a scheme worthy of an Ian Fleming novel and it succeeded for two years before Friedland was discovered operating a scuba diving business in the Maldives, an island nation in the Indian Ocean, where he’d been hiding out.

It was later revealed that while in the Maldives, Friedland had been in touch with Libya’s dictator Muammar al-Ghaddafi, seeking asylum.

Those who knew him in New Jersey chuckled and shrugged their shoulders at the revelation: Hey, it was David Friedland. Who else do you know who’d negotiate his freedom with a despot and dictator?

The myth grew even after his incarceration when he made a deal with the Drug Enforcement Agency to provide information on drug trafficking, information which eventually led to the recovery of Stinger missiles in Afghanistan.

Again, to his acquaintances in New Jersey, it all made sense --- Friedland, drug deals, Stinger missiles, Afghanistan. It was, after all, David Friedland.

He was released to a halfway house in Florida in 1997 after serving eight years in prison.

People like Friedland are often referred to as unscrupulous, immoral individuals who use their public positions for private enrichment, reinforcing the image of politicians as greedy, grasping individuals without conscience.

They are also lamented as people who, had they turned their energies, ingenuity and intellect toward honorable pursuits, could have made a considerable difference.

They fell victim to hubris, a belief they were superior to others and could avoid consequences for their actions. They could fly too close to the sun with impunity.

Friedland was not victimized by hubris, though. For him, flying too close to the sun was a challenge that he believed he could overcome.

There was always a deal to be made; an accommodation to be reached; favors to exchange; promises to be offered; compromises to be struck all to avoid the sun’s heat.

He damn near got away with it and secured his place in Hemingway’s moveable feast.

Carl Golden is a senior contributing analyst with the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton University.

I’m writing his book and screen play. David was a close friend and he shared a lot of his life with me over the past 20 years. I’d love to get more information.

I was his case manager at the Federal work release and i could definitely add to this story.