Newark and the Imperative of Eliminating Environmental Racism

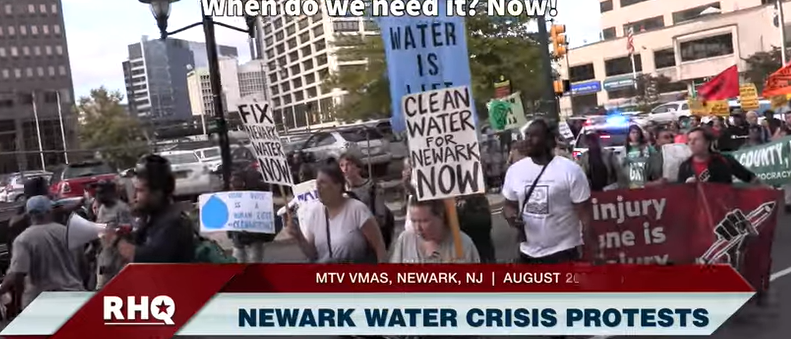

Of all the New Jersey political stories I have written about since I began my life as a political columnist in 2009, I find the Newark water crisis to be the most compelling. It is a mistake to view the Newark story in isolation from clean water environmental issues existing in other venues in America. Indeed, it is a national story of supreme importance in two significant respects.

First, as I have written, there is a need for over $500 billion nationally to finance necessary replacement of deteriorated water infrastructure, and the Newark situation is an archetypal example of this necessity. The Essex County bond package assistance to Newark announced on Monday could prove to be a national model for financing such infrastructure, at least until a national scale infrastructure financing plan is passed by Congress. As I said, however, in my previous Insider NJ column, “Newark and the Politics of Clean Water” (https://www.insidernj.com/newark-politics-clean-water/), it is most unlikely that that there will be public support for such a national water infrastructure funding plan, financed by a water usage tax until the clean water tragedies of Flint, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey spread to suburban white America.

The second matter is a broader environmental issue and in many ways one of historic significance. That issue consists of the twin components of environmental justice and environmental racism. White Americans are largely unaware of these issues. Yet there is no doubt that Newark historically has been a major victim of environmental racism. The lead service line crisis in Brick City is a clear manifestation of this.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the "fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies." Conversely, environmental injustice exists when one group of people is exploited to benefit another, leading to a lesser degree of environmental protection for the exploited.

The most frequently cited example of environmental racism and injustice is the fact that a higher percentage of hazardous waste dumps are located in or near lower-income or minority communities. Yet the condition of the lead service lines in Newark is no less an example of environmental racism than the siting of hazardous waste dumps.

This year is the 400th anniversary of the entry into America of African-Americans as slaves. I never forget that while my grandparents came here voluntarily from countries that were in reality lands of exile for the Jewish people from their ancestral homeland of the land of Israel, African-Americans were brought to America against their will in chains from their ancestral homeland and deprived of their heritage.

Once they arrived, African-Americans were first subjected to the extreme cruelty of slavery until the end of the Civil War in 1865. Margaret Mitchell’s book, Gone With the Wind and the movie version were despicable efforts to lull White America into the false belief that slavery was a benign institution. I urge my readers to read the 2019 Pulitzer Prize winning book, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by the eminent Yale professor David Blight to learn the full horrific nature of the Southern enslavement of African-Americans.

Since the end of Reconstruction, African-Americans throughout the nation have been subjected to a veritable plethora of different forms of racist injustice, including discrimination in housing, jobs, education, police brutality, and voting rights.

The impact of environmental racism is arguably, however, the most malignant and virulent. Due to environmental racism, African-Americans are far more subjected to the dangers of environmental hazards than their fellow white citizens, particularly with respect to lead. Once environmental racism has resulted in a negative health impact on an African-American, the damage, more often than not, can never be remedied. And when environmental racism results in damage from lead to an African-American child, the victim potentially will suffer from lifelong learning disabilities, destroying his or her economic prospects.

The new book, A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and Its Assault on the American Mind, written by the renowned Yale professor Dr. Harriet A. Washington, documents in powerful detail the disproportionate exposure of African-Americans to environmental hazards, ranging from lead poisoning to the devastating effects of atmospheric pollution, infectious disease, and industrial waste. Americans are, for the most part, only now beginning to grasp the horrors of environmental racism.

The current water crisis in Newark is a direct outcome of environmental racism, resulting from racism in housing and jobs. The great majority of Newark’s African-American population arrived in Brick City as part of the great 20th Century migrations from the South to northern urban America. There, these Americans of color fell victim to virulent discrimination in job opportunities, resulting in their impoverishment, and in housing availability. These two racist malignancies resulted in African-Americans being severely restricted to substandard housing, with lead service lines most likely to deteriorate and leach lead than newer dwellings from which they were barred.

Environmental injustice is more often than not an horrific outcome of past white exploitation of their fellow black citizens. In Newark and in Flint, Michigan, we are now seeing how horrific the damage from environmental racism can be.

A New Jersey not good for all of us is not good for any of us. The elimination of environmental injustice and racism is a New Jersey imperative. And Newark is the best place to start.

Alan J. Steinberg served as Regional Administrator of Region 2 EPA during the administration of former President George W. Bush and as Executive Director of the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission under former New Jersey Governor Christie Whitman.

Seems to me you are conveniently forgetting one person - Cory Booker was the failed mayor of Newark at the time Lead was found to be climbing in the water levels. Let me remind you - he's black. Second, rather than Newark fixing it's own infrastructure you are trying to pass it onto "suburban white America". That's a pretty damn racist comment if I ever heard one! Alan Steinberg, you should be ashamed of yourself! Will Newark step-up and pay for the roads outside my home to be repaved? I think not! How about putting the blame right where it needs to be - the people of Newark themselves! They keep electing democrats to run their city and what do they get - incompetence!

The City has been run by African-American mayors since 1970, who did nothing.