Of Cookies and Cars: Running the Border Squeeze Play

It’s a tough fact of life but ignoring it won’t change it whereas confronting head on just might. Unions continue to be at a distinct disadvantage in a system where corporations use the legal system and their vast wealth to violate labor law with impunity.

And if you have a problem with that, they can threaten to just leave town. Take the exit of Nabisco, aka Mondelēz International, from Fair Lawn.

Understandably, Fair Lawn’s municipal officials are now doing their best to put the best spin on the demolition of the iconic Nabisco plant in Fair Lawn which for over half a century provided several hundred good paying and family building union jobs.

Back in 2021, Nabisco’s multinational parent Mondelēz sold the property on Route 208 to a CLPF Greek Fair Lawn LLC, a development and construction company, for $146.5 million. Over the previous summer the global snack company shut down its cookie production operation despite the strenuous union and local political opposition.

“We’re really excited," Mayor Kurt Peluso told NorthJersey.com . "I think that it shows a lot about the community of Fair Lawn that we had such a large company leave and the property never went dormant.”

Municipal officials noted it had avoided the burden of a new residential complex at the site and that Mondelēz was still paying it’s $1 million in property taxes even after production had gone dormant. “Not a dime was lost,” Peluso told the newspaper.

JUST DESERTS

But what hasn’t been widely reported was the way that before the global snack giant shut down the Fair Lawn plant, it illegally terminated veteran leaders of Local 719 of the Confectionery, Tobacco Workers & Grain Millers International Union by falsely accusing them of stealing time from the company.

Ultimately, the company had to pay $2.3 million to three of the former Nabisco employees who “were unlawfully suspended and terminated in retaliation for their Union support or otherwise engaging in protected concerted activities,” according to the NRLB 2020 decision. “The three employees in this case were icing mixers and floor helpers at the plant and were active in the Union for many years prior to their unlawful discharges.”

The multi-billion-dollar company only relented after a unanimous three-judge panel of the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Mondelēz actions “was sufficient evidence of anti-union animus that violated the National Labor Relations Act,” Reuters reported. The court also upheld the NRLB’s finding that the company made “unlawful unilateral changes to working conditions after a collective bargaining agreement expired.”

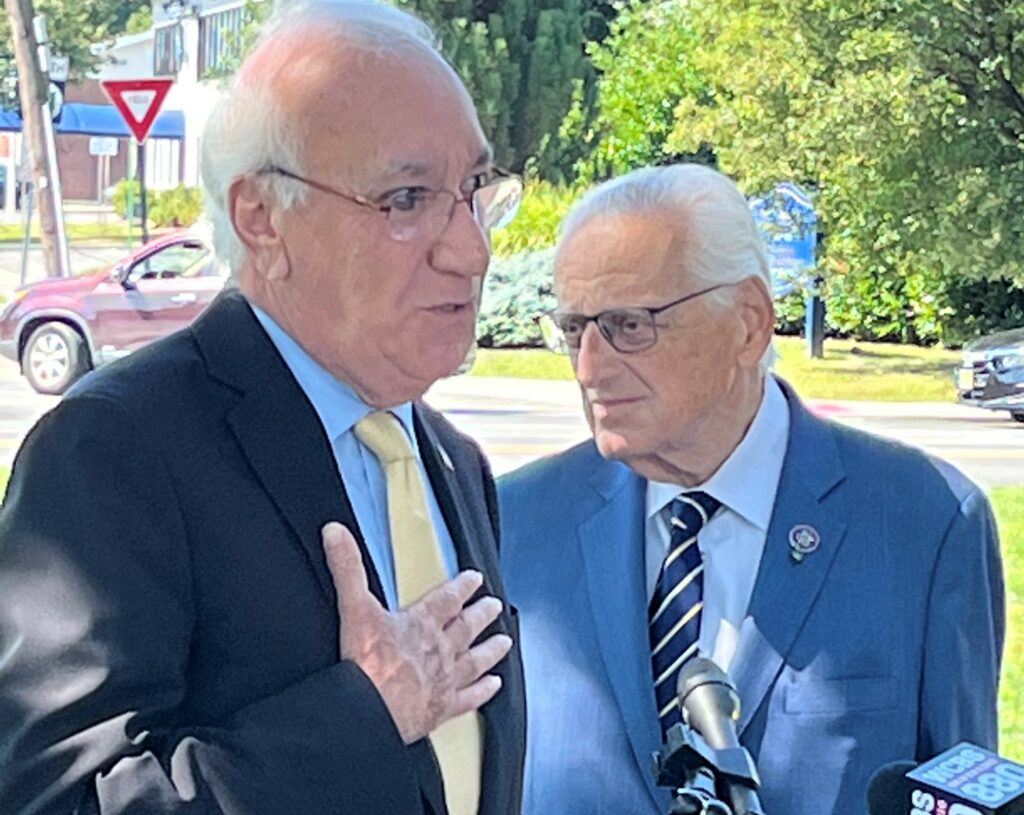

Back in 2021, Rep. Bill Pascrell (D-NJ-09), wrote a letter to Dirk Van de Put, CEO of Mondelez demanding information on the company’s closing of its Fair Lawn plant and the company’s outsourcing of American jobs.

“Eliminating good paying union jobs here in the United States while creating low-wage jobs abroad may benefit your corporate bottom line, but it drives race-to-the-bottom conditions,” Pascrell wrote. “These practices have devastating impacts to workers, their families, and communities across our country as this nation struggles through the pandemic. We seek further details concerning Mondelēz’s policy of paying workers in Mexico low wages and how it may relate to the elimination of United States jobs. Reports that the company has been demanding cuts to wages and benefits in factories across the United States appear related to decisions to invest in and move operations to Mexico.”

In September 2021, Nabisco workers at five locations in Oregon, Colorado, Virginia, Illinois and Georgia went out for strike for a week after the company pressed for significant concessions despite a 12 percent spike in annual revenue for the multi-billion-dollar Chicago based multination.

GLOBAL SQUEEZE PLAY

As in the case of the former Ford Motor Company plant in Mahwah on Route 17, which closed down production in 1980 and was leveled in 1984, the history of the Fair Lawn cookie plant reveals a lot about how globally scaled capitalism uses its leverage to squeeze the labor movement. In the process, this works to create an economy that only works for the wealthy.

Publicly traded multinationals cover their anti-labor tracks with phony corporate codes of conduct proclaiming their environmental sustainability and community engagement.

It’s no accident that as union density declined here in the U.S. wealth concentration and income disparity exploded as did the amount of money that flooded into our politics to continue to grease the skids.

In 2020, Forbes reported the Federal Reserve found that the top one percent of Americans had a combined net worth of $34.2 trillion in wealth, or 30.4 percent of all U.S. household wealth, while the bottom 50 percent of the population held just $2.1 trillion, or 1.9 percent of all wealth.

And while last year’s successful David versus Goliath win by the independent Amazon Labor Union winning its election at Amazon’s largest Staten Island distribution center made headlines, the global giant continues to successfully resist with a scorched earth legal strategy eight months later despite the certification of the union victory this month.

Sure, nationwide there’s been a 53 percent jump in petitions to the National Labor Relations Board for union recognition with FY 2022 seeing 2,510 such applications, up from 1,638 in the previous fiscal year. Meanwhile, unfair labor practice charges filed with the have spiked 19 percent to 17,988 from 15,082 over the same period.

ONE IN TEN

But the reality is that in our 21st century America, despite all of these on the ground organizing efforts, the nation’s union density, the percentage of Americans in a union, declined last year to the lowest on record, from 10.3 percent to 10.1 percent, according to the U.S. Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics. “In 1983, the first year where comparable union data are available, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent and there were 17.7 million union workers,” the BLS reported.

There’s a considerable gap between the states when it comes to union density with so-called ‘right-to-work’ states below the Mason Dixon line like South Carolina, with just a 1.7 percent union membership rate as contrasted with Hawaii at 21.9 percent, New York with 20.7 percent and New Jersey hovering just over 16 percent.

What hasn’t changed is that union members out earn non-union workers on average $1,216 to $1,029 a week. And based on recent research it appears that union workers and the people they served in education and congregant care facilities fared better health wise during the pandemic.

While only 17 percent of the U.S. nursing homes are unionized, the Washington Post reported that had “the entire U.S. nursing home industry had been unionized, it could have prevented 25,000 workers from being infected and saved 8,000 nursing home residents from dying during the 10 months from June 2020 and March 2021.”

This shrinking of the union movement got traction after President Reagan’s mass firing of the nation’s air traffic controllers in the early 1980s and continued to accelerate with President Clinton’s North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s.

This sad saga played out up in northwest Bergen County in Mahwah, where in 1950 the Ford Motor Company built its then state of the art vehicle assembly plant, which at the time was the largest such plant in the country. It was so productive it required around the clock freight rail service on the Erie Lackawanna.

CASHING OUT US WORKERS

Of course, Ford, like all the other U.S. originated multinationals, exploited U.S. tax policy that incentivized abandoning Main Street for anywhere else on the planet where wages were lower and environmental regulations non-existent or lax. This has been a bi-partisan accomplishment with both Democratic and Republicans doing their largest donors bidding by fashioning a tax code that promotes the amassing of great wealth by taxing our labor at a much higher rate than capital.

While the water tower with the Ford logo disappeared the toxic paint sludge from the plant dumped by organized crime in the abandoned iron mines in the Ramapo Mountains endures. On the site where there had once been 5,000 United Auto Worker union jobs, no doubt local officials cheered when Sheraton committed to build a hotel on the site.

In that 172-acre Mahwah site we have the entire arc of America’s shift from a high wage manufacturing powerhouse to a low-wage service economy. By 2008, Reuters reported UAW membership had dropped below 500,000 “its lowest level since World War Two in a downturn that reflects the wrenching restructuring by U.S. automakers.”

In just one year, the rolls one of America’s most significant unions plummeted by 14 percent from 464,910 in 2007, as compared to its peak year in 1979 when it was approaching 1.5 million. Then Ford pulled up stakes and shifted production to Mexico for import into the U.S., a strategy that was put on steroids economy wide after NAFTA was enacted.

This globalization was financed on a wave of ever larger junk bond deals that over leveraged what was left of America’s productive economy, a trend that was also aided and abetted by the U.S. tax code.

And while Wall Street reaped the from the LBO windfalls, where borrowed money was used to buy up one company after another, it was American workers and their families caught in the squeeze play. Profits were not invested in the workforce or in research and development but to pay off corporate debt and obscene CEO bonuses.

BOWLING ALLEY BLUES

Consider the 1988 eyepopping $25 billion purchase by Kohlberg, Kravis, and Roberts of RJR Nabisco which owned the Fair Lawn plant. It got the ball rolling.

I was working at the Ridgewood News back then. When the deal was announced, I headed over to the Brunswick Fair Lawn Bowling Lanes where I knew the Nabisco workers bowled. They were worried their bakery would be closed and their jobs sent south.

“It’s all greed,” one union worker told me. “What happened? They are going to put a $25 billion mortgage on Nabisco, that’s what happened. They’ll make it up by closing plants and hacking up the company and the government just stands by.”

Indeed.

Liberal nonsense. Did it ever cross the reporter's mind that NABISCO, like many other companies Does Not Want To Do Business in NJ? What does a 1988 business deal have to do with company relocation in 2023??

Excellent reporting and insight.