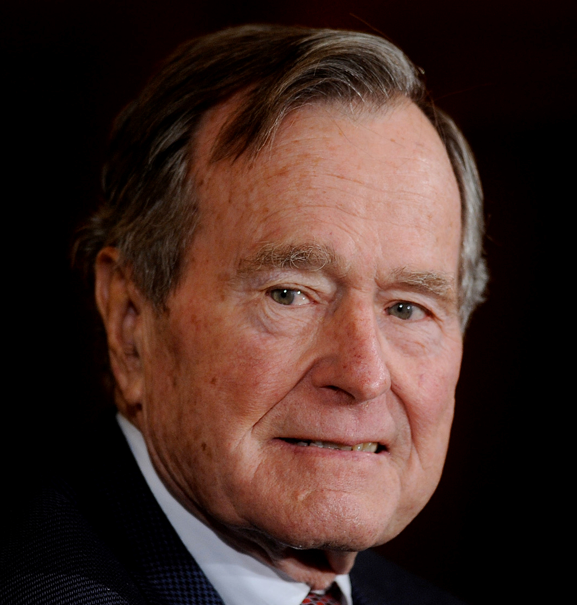

THE PASSING OF PRESIDENT BUSH SERVES AS A REMINDER ABOUT THE NEED FOR CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM IN NEW JERSEY

The death of President George H.W. Bush, who served the nation with grace and humility, rekindled many memories. One was how dramatically political fundraising has changed since 1988, the year of his election.

Back then, national political parties could accept unlimited, sometimes very large contributions for “voluntary purposes.” These informally were called “soft” money contributions. The term was used to contrast them with “hard” money contributions, which are subject to tight limits.

Unregulated soft money to political parties was eliminated in 2002 with the enactment of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), otherwise known as McCain/Feingold.

What followed was a decline in party fundraising and influence even after soft money had helped restore state and local party committees. The ban also led to an explosion of independent spending by special interest groups uncontrolled by parties or candidates and less transparent to voters.

According to the late Herbert E. Alexander, Director, Citizens’ Research Foundation, University of Southern California, one of the purposes of soft money was “to allow state and local party committees to undertake such activities as registration and get-out-the-vote drives, phone banks and the like—activities directed at stimulating citizen participation.”

Alexander, a campaign finance expert who served as Executive Director of President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on Campaign Costs and a one-time consultant to ELEC, noted that soft money could also be used for party generic advertising.

He added “soft money was not devised to be a loophole; rather it was a conscious effort by Congress to empower state and local party committees in federal campaigns.”

The use of soft money by national parties came about as the result of amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) in 1979.

David E. Price, a state party chairman and college professor, wrote “assuming that some loopholes for party initiatives are desirable, the 1979 provisions seem, on balance, to be well conceived. They open up the possibility of a significant campaign role for state and local organizations.”

Alexander and Price agreed that unregulated party money not only enhanced parties at the state and local levels but encouraged citizen participation.

Soft money, which was transferred into state and local federal accounts, was not directly responsible for the resurgence of the party system in New Jersey in the 1990s.

But it helped.

What soft money did was keep parties alive during the 1980’s when New Jersey’s party system became moribund, in part because of suburbanization, an open primary law, and the introduction of gubernatorial public financing.

In terms of the impact of soft money on state and local party committees, Indiana University Political Scientist Marjorie Random Hershey wrote: “State and local parties, energized by money received from the national parties . . . became more involved in campaigns. Some put major effort into the labor-intensive grassroots work that was the staple of party organizations in an earlier era.”

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, by eliminating soft money, had a negative impact on grassroots efforts by parties at the state and local level. Moreover, an unintended consequence of BCRA was that it ushered in the era of independent groups and Super PACs.

Beginning at the federal level, wherein independent spending grew by over 1000 percent between 2002 and 2008, two years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United (2010) would further facilitate this growth, this outside group spending would come to dominate even state and local elections.

In New Jersey, independent group spending has recently eclipsed spending by political parties. Though responsibility for this development cannot be solely placed at the doorstep of soft money’s elimination, BCRA’s end to soft money was the first shot across the bow.

Beginning in the gubernatorial elections of 2009, and culminating in expenditures reaching almost $50 million in this year’s Congressional elections, independent groups are now drastically over-shadowing political parties on New Jersey’s electoral landscape. Parties again are becoming largely irrelevant as they were in the 1980s.

This is why there is an urgent need for legislation that would offset the growing influence of independent groups and strengthen parties.

Legislation introduced by Senator Troy Singleton and Assemblyman Andrew Zwicker (S1500/A-1524 and S1479/A-3462) would together require disclosure by independent groups and strengthen political parties in New Jersey.

Other provisions in the package of bills, which incorporate bipartisan recommendations made by the Election Law Enforcement Commission, would serve to bring back balance in the electoral system between accountable parties and often times anonymous independent groups.

Passage of this legislation would be in the broad interest of the public and the integrity of the state’s electoral system.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission