Hughes Center Report Shows U.S. District Court in N.J. Faces Huge Case Backlog

| Hughes Center Report Shows U.S. District Court in N.J. Faces Huge Case Backlog |

|

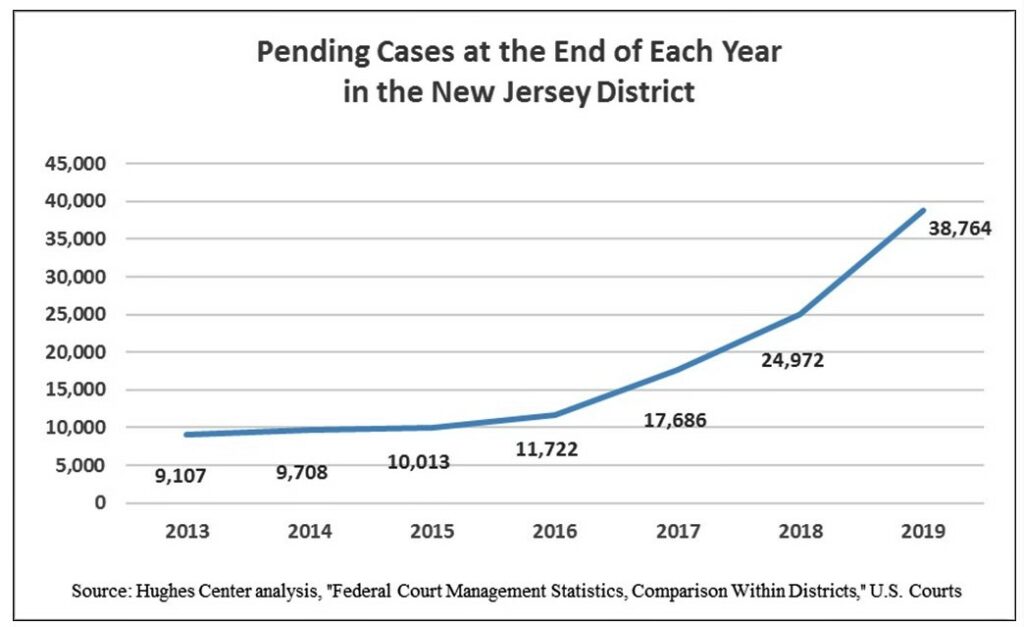

Galloway, N.J. – The U.S. District Court case backlog in New Jersey has grown by 230% since 2016 and now stands at almost 39,000 cases. The cause is a combination of unfilled vacancies on the federal bench combined with a surge in federal case filings, according to a student research paper published today by the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton University. New Jersey’s federal case backlog, known as pending cases per judgeship is larger than the backlog in Pennsylvania, which covers three district courts to New Jersey’s one, and edges out New York State, which encompasses four district courts. New Jersey has more pending cases per judgeship than the Southern District of New York, considered to be one of the busiest districts in the nation, according to research authored by Daniel Tidcombe, a Stockton University political science major who graduated in May. Tidcombe served as the Hughes Center’s research intern for the spring 2020 semester. The backlog of pending federal cases stood at nearly 39,000 at the end of 2019, the last quarter for which data are available. “Justice delayed means that thousands of parties to civil and criminal cases in New Jersey are left hanging with little hope of a speedy trial,” said John Froonjian, executive director of the Hughes Center. “The judicial vacancies and backlogs seriously affect the administration of justice, and it is hurting New Jersey more than other nearby states.” The research project was prompted by a Jan. 23 Hughes Center speaker event featuring former White House Counsel Don McGahn, at which he said vacancies and resulting backlogs exist on the New Jersey federal bench because of the U.S. Senate tradition of home-state senators being able to hold up judicial appointments by not signing off on them. Republican McGahn said Democratic Senators Robert Menendez and Cory Booker have not allowed Trump administration nominees to move forward by submitting “blue slips” that would indicate their approval. The Hughes Center asked representatives of Menendez and Booker multiple times for their response but did not receive a reply. Tidcombe’s analysis of federal court data showed six of 17 District Court judgeships in New Jersey are vacant. The vacancies, measured in the court reporting system as months per year a vacancy exists, is up from only two vacancies in 2018. A few judges in New Jersey have stayed on past retirement age to help handle cases, including two in the federal courthouse in Camden. But no new full-time judges have been appointed to fill those vacancies, even as the number of cases coming before the judges has swelled by 62% since 2017. The district court handles cases on constitutional issues, acts of Congress and maritime law, but also is assigned multi-district cases that can combine numerous individual cases, sometimes numbering in the hundreds. The number of cases related to the pharmaceutical industry has also risen, one judge told Tidcombe. “Recent years have seen an unprecedented and significant jump in total case filings in the New Jersey District Court. This jump has coincided with several vacancies opening up on the bench,” Tidcombe wrote in his report. “This in turn means that fewer judges are available to shoulder the increased burden, driving up the number of cases each judge must take on,” he said. Highlights of the analysis include:

As part of his research, Tidcombe interviewed Judge Joseph Rodriguez, a District Court judge who sits in Camden County. At age 89, he could have retired years ago but continues serving. As a senior judge, Rodriguez could request a caseload as low as 25 percent of a regular judge’s load. But he handles a full caseload because the other federal judges in Camden would have to pick up the slack. “They’re already drowning the way it is,” he said. Rodriguez noted that the workload is even greater than case numbers suggest because they don’t include hearings on trial motions and sentencings. “There obviously is a massive problem in the District of New Jersey,” Rodriguez said of the backlog. The judge, a Camden native who received his degree from Rutgers School of Law-Camden in 1958, said he refuses to cut corners to reduce backlog numbers. He said each case represents individuals seeking justice. “There are nights where you go to bed and you can’t sleep because you’re worried about a decision you have to make because you’re affecting people’s lives. You just (can’t say), ‘Ah, I got rid of the case.’ “I would hate to think that in order to improve your numbers, you’re injuring people and injuring their rights. I think you fail in your obligations as a judge if you put numbers ahead of the rights of a litigant,” he said. The full research report is online at www.stockton.edu/hughescenter. About the Hughes Center |