Redistricting Case Could Trigger Surge in Campaign Spending

The U.S. Supreme Court will take up a case in the fall that could change the way legislative districts are redrawn and potentially increase the amount of money spent on politics by making legislative elections more competitive.

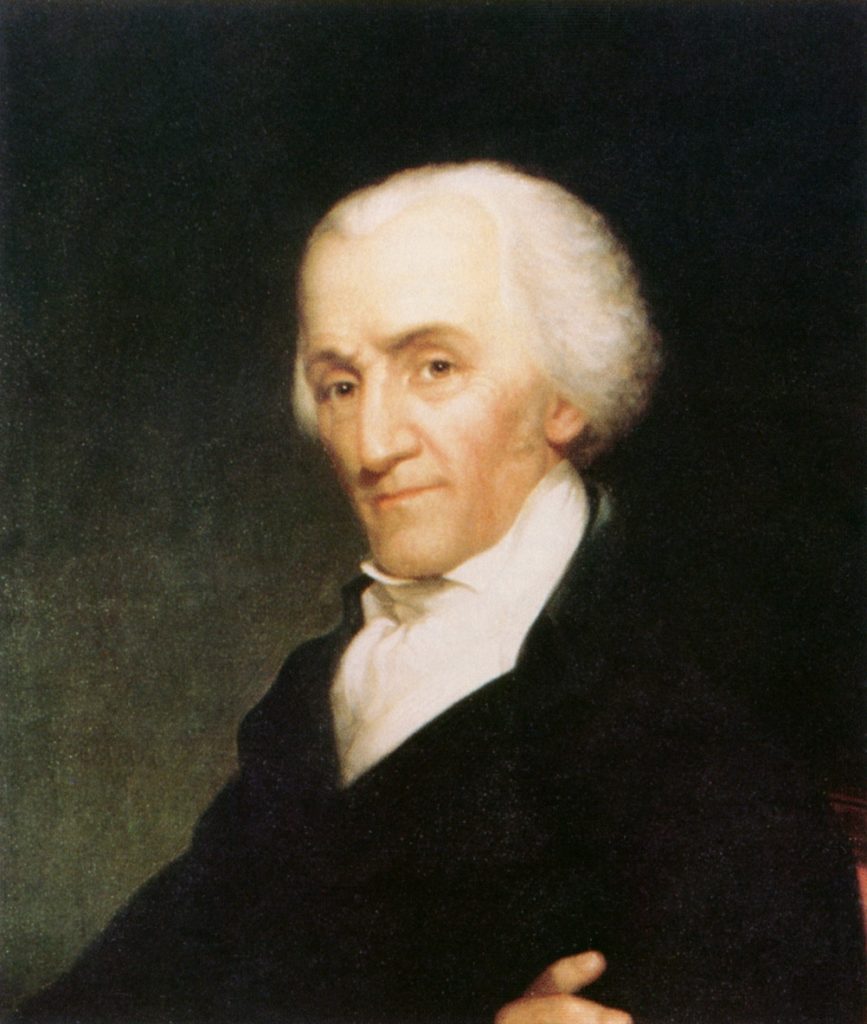

In Gill v. Whitford, the High Court will hear a challenge to partisan gerrymandering. Gerrymandering is an effort to redraw voting district lines to benefit one party over the other. The long-time practice is named after Massachusetts Governor Eldridge Gerry (pictured), who, in 1812, served while the Legislature created a salamander-shaped district.

A ruling by the District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin held that the statewide legislative district map configured in 2011 by the Republican-controlled Legislature violated the equal protection clause and First Amendment rights.

In other words, the District Court maintained that the partisan gerrymandered map was unconstitutional.

Alleged partisan gerrymandering by Maryland Democrats is also being challenged in federal district court, though that case may be put on hold pending the outcome of the Supreme Court case.

In Wisconsin, the District Court ordered the Legislature to put a new map in place by November, in time for the 2018 election.

The State of Wisconsin, in turn, appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, and requested a stay of the lower Court’s Order, which was granted January 19, 2017, with the Court setting argument for October 3, 2017.

If the U.S. Supreme Court finds gerrymandering for partisan reasons to be unconstitutional, it would be charting new territory.

For most of its history, the Court has been reluctant to enter into areas it deems a “political question,” with redistricting being one such question.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1960, some 172 years after the Constitution was ratified, that the Warren Court first took up a question of racial malapportionment.

Related to gerrymandering, malapportionment involves drawing district lines based on unequal representation for the purpose of benefiting one party over the other.

In Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960), a plan by the City of Tuskegee, Alabama that would have excluded African-American voters from the city limits was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Finally, in Baker v. Carr (1962), the High Court considered a case that would have ramifications for every voter throughout the nation. For the first time, the Court ruled that “reapportionment,” or redistricting based on population, was no longer off limits as a political question.

It wasn’t until a year later, though, in Gray v. Sanders (1963), that Justice William O. Douglas pronounced the principal of “one person, one vote.”

This decision set the stage for legislative districts to be drawn based on the doctrine of equal representation.

Since then the U.S. Supreme Court has been less reticent about ruling in cases involving redistricting.

While the Court has ruled in cases involving variations in population numbers between voting districts, the thrust recently has involved cases of racial gerrymandering.

In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the Court disallowed gerrymandering based on race unless the government could demonstrate that it has a compelling reason to create minority—majority congressional districts.

If demonstrated that establishing Black or Hispanic districts would increase minority representation in Congress, they would be permitted. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court in Hunt v. Cromartie (2001) upheld racial gerrymandering in North Carolina’s twelfth congressional district.

Though as often happens in human affairs, a good idea is carried too far, thereby abused. This explains why federal courts are now dealing with a handful of cases, from North Carolina to Texas, that involve over-populating certain districts with minorities in order to create an increase in districts favorable to the party in power.

While the courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have not hesitated to rule on cases involving racial gerrymandering, they have been more reluctant to engage challenges to partisan gerrymandering.

This is why Gill v. Whitford is viewed as potentially precedent-setting.

It is the first case since Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004) that the U.S. Supreme Court will adjudicate the issue of partisan gerrymandering. In the 2004 case, the Court could not agree on a test to determine when partisan gerrymandering becomes unconstitutional.

In Gill v. Whitford, Justice Anthony Kennedy will again likely be the deciding vote. While the judges in the 2004 case ultimately could not settle on a standard for deciding when partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, Justice Kennedy was the deciding vote in the majority that agreed the matter was within the court’s jurisdiction.

If the U.S. Supreme Court does conclude that Wisconsin’s legislative district map is unconstitutional, it will have ramifications not only in terms of how redistricting is done but in terms of campaign finance.

Minimizing partisan gerrymandering would make legislative elections more competitive, thereby increasing participation and interest in the outcome of those contests. This interest and increased competitiveness would add another dimension to the field of campaign finance.

Not only will candidates and political parties be driven to raise and spend mounting dollars, but special interests will be squeezed even more with pressure to give to both sides in this more competitive atmosphere.

Further, independent groups will continue to grow, increasing their already formidable clout. And with more competitive elections, creative ways of raising and spending campaign related dollars are sure to emerge.

In deciding Gill v. Whitford, the U.S. Supreme Court could make the redistricting process the domain of the judiciary rather than state legislatures. This could impact overall on the electoral system, including, but not limited to, campaign finance.

Because of the significance of this issue, the October 3, 2017 hearing is worth everyone’s attention.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.