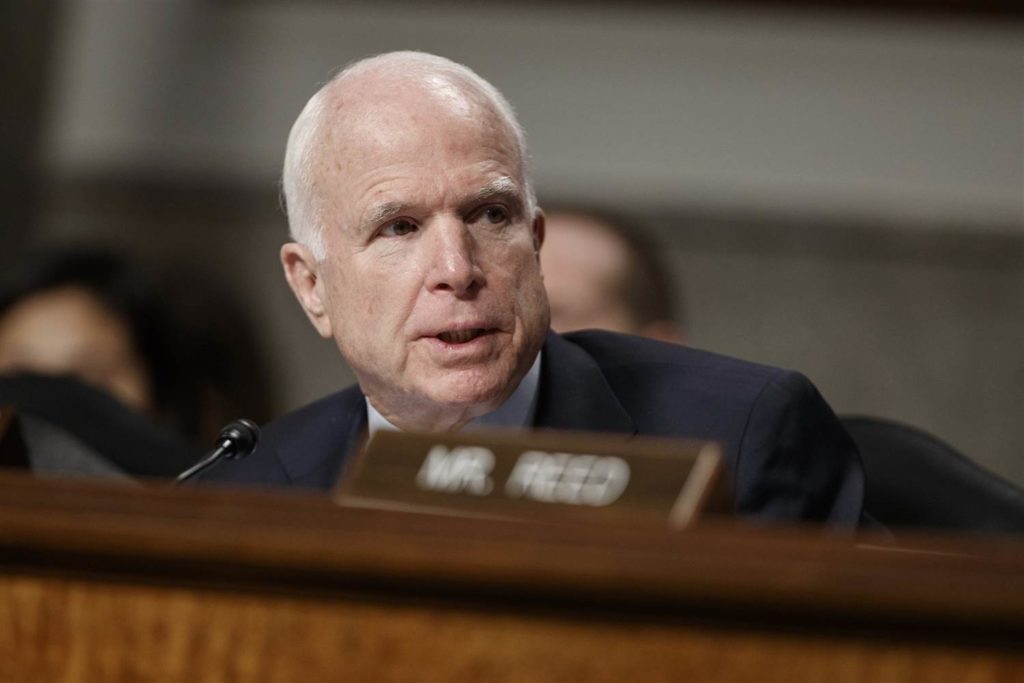

Sixteen Years Later, the McCain Feingold Law of 2002 Appears More Boomerang than Reform

Sometimes well-intentioned reforms have unintended consequences.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), often referred to as McCain/Feingold, was enacted in 2002. Though well meaning, McCain/Feingold sparked the rise in dark money spending and a spate of legal action.

Among the provisions of the Act was a ban on “soft” money contributions to national party committees. In other words, donors could no longer contribute unlimited amounts to the Republican and Democratic national committees.

Contributions to the national committees became subject to tight contribution limits, replacing “soft” money with “hard” money.

McCain/Feingold also prohibited issue and express advocacy advertising within 30-days of a primary and 60-days of a general election.

As predicted at the time by me and others, the ban prompted a stampede of donors away from the national parties and toward independent, outside special interest groups that were far less accountable and transparent.

Just between the enactment of BCRA and 2008, there was more than a 1,000 percent growth in independent group spending at the national level. This spending ultimately filtered down to the states, including New Jersey.

Immediately upon enactment of BCRA, a lawsuit challenged its constitutionality. Senator Mitch McConnell and a variety of interest groups targeted the soft money ban and the advertising blackout periods before elections.

A ruling by the D.C. District Court upheld most of BCRA but struck down the soft money ban. The U.S. Supreme Court took up the case, rendering an opinion on December 10, 2003.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court upheld as constitutional most of BCRA, including the soft money ban, the 30- and 60-day blackout periods, and the ban on corporate and union independent expenditures.

What came next, however, demonstrated that despite the McConnell decision, BCRA was far from settled law.

In Federal Election Commission (FEC) v. Wisconsin Right to Life (WRTL), the non-profit group maintained that its advertisements were issue ads and as such should be allowed to be aired during the blackout periods. The ads encouraged U.S. Senators to oppose filibusters of judicial nominees.

By virtue of a 5-4 decision on June 25, 2007, the Supreme Court began the process of chipping away at the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act. It ruled that pure issue ads were not subject to the ban imposed on express advocacy during the periods prior to primary and general elections.

The Court, in WRTL, came down on the side of “speech, not censorship” and established the functional equivalent of express advocacy test. The test held that an ad is subject to the restrictions under BCRA “only if the ad is susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an appeal to vote for or against a specific candidate.”

Other rulings further chipped away at BCRA, such as Davis v. FEC (2008). In this case, BCRA’s millionaire’s amendment allowing congressional candidates opposed by self-financed candidates to triple their contribution limits was struck down by the high court,

The situation truly reached critical mass in the Court’s Citizens United v. FEC ruling on January 10, 2010.

The 5-4 majority overturned as unconstitutional Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990), which had banned corporate and union independent expenditures. Austin was a departure from the landmark Buckley v. Valeo (1976) decision.

In Citizens United, the Court determined that the 30-day and 60-day blackout periods on express advocacy were unconstitutional hinderances to free speech.

Thus, the Supreme Court in Citizens United all but eviscerated McCain/Feingold. It did sustain the ban on direct contributions to candidates and political parties by corporations and unions, and strongly endorsed the disclosure of campaign advertisements even if they went beyond the functional equivalent of express advocacy.

The unintended consequence of McCain/Feingold was to light the match that sparked the growth of independent spending often was done with no donor disclosure. Citizens United further fueled this raging forest fire of “dark money” spending. After the 2010 ruling, independent group spending took off exponentially in federal, state and even local elections.

Other decisions would follow that would further the growing influence of independent, dark money groups, such as SpeechNow (2010), which said independent expenditure-only committees could accept unlimited contributions, and Carey v. FEC (2011), which further clarified that corporations and unions could make unlimited contributions to 527 political organizations.

In the end, a 2002 law intended to reign in election spending backfired by triggering an era of court-ordered deregulation that led to massive new spending.

Throughout the modern era, it has become abundantly apparent that changes in campaign finance law, as well as court decisions, determined the flow of money within the political system. Though it may be desirable on the part of some to stem the flow of money in politics, history has shown it is not going to happen.

Money always finds its way into elections.

In New Jersey, it would be best to remember that adage and enact laws that will redirect the flow of contributions back to more accountable, transparent political parties and the candidates themselves.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.