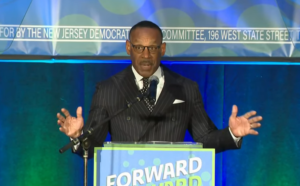

Speaker Coughlin, His Agenda, and the New Trenton Triumvirate

Speaker Craig Coughlin (above left) was never a conundrum. He was with Steve Sweeney, and then he was with Phil Murphy, without ever breaking a sweat or changing expression. In the name of a never wavering devotion to the Middlesex County Democratic Organization (MCDO), he stayed in place, affixed as needed to either the party machine-domineering senate president from South Jersey, or the neophyte middleclass-on-a-good-day governor from Wall Street: the personification of a painting of a personage at the Statehouse, which might reside closer to another portrait one moment, and then become repositioned with greater proximity to another portrait the next.

Thus, he suction cupped himself to Sweeney in the early days of the Murphy administration, then did not appear with Sweeney, while never objecting to Sweeney's public declaration's in opposition to Murphy that "Coughlin feels the same way," then gradually surfaced with a greater degree of comfort at the side of Murphy, sturdily present while Sweeney sheepishly finally backed Murphy's millionaire's tax, for example, shortly before the voters of South Jersey made Sweeney vanish from the halls of Trenton, leaving Coughlin snugger than ever at the governor's side.

It all happened emotionlessly and undramatically, with the speaker reserving his only demonstration of

"outrage" - his word of choice - for Republican lawmakers attempting a lifeless mini-reenactment of the Jan. 6th insurrection. In accord with the directives of the MCDO, which at that time still fashioned itself a pretty solid ally of the Camden Democratic Organization, he sedately backed LeRoy Jones for the position of Democratic State Party Chairman, then remained sedately in support of Jones even after Camden - infuriated by Jones cutting the deal for party leadership without first conferring with them - decided it no longer liked Jones. Jones was fine with MCDO Chairman Kevin McCabe, so Coughlin was fine with Jones. The uncoupling from Sweeney occurred in quiet concert with the clerical reality of Coughlin and his other caucus members occupying the party line under Murphy, who was also running for reelection.

Coughlin was on the line with Murphy, not Sweeney, so - like the organization that spirited his political fortunes - he was closer to Murphy.

The question now, with Sweeney gone and a new senate president in place who depended on the MCDO

to attain the throne, is what will Coughlin do amid an uptick of whisperings about Middlesex's intention to plant him on the gubernatorial throne when Murphy leaves? Will he simply continue to stay in place, occasionally creaking like a weather vane in a spaghetti western while the organization relentlessly asserts itself underground? Will Murphy's increasing forays outside of New Jersey as he attempts to do better than Bradley-Christie-Booker as a Garden State presidential candidate, require Coughlin to assert himself in a way he hasn't before? Will an increasingly nationally distracted Murphy put Coughlin in the position of mustering a firmer grip on the reins of state government? Sweeney had an agenda. He even went so far as to drive around the state to deliver it firsthand to voters. Will Coughlin do the same? Will Coughlin attempt to be closer to Sweeney politically, that is to say, pragmatic, as Murphy attempts to expand to greater ranges of progressivism in his quest to become a legitimate national brand? Sweeney once delighted in playing the role of chastising adult to Murphy's childlike liberal, with Coughlin content to fulfill the part of unflappable older brother. In light of Democrats' measly three percentage point gubernatorial victory and Assembly Democrats in the Murphy-Sweeney-Coughlin era sliding from 54 members to 52 to 46, will Coughlin don a more Sweeney-like budget time game face in an effort to corral independent voters and stem the red wave that doomed the senate president?

Republicans over the course of the past two years have strengthened their position in the southern part of the state, gaining LD1, welcoming U.S. Rep. Jeff Van Drew’s party affiliation change from Democrat to Republican, and this year adding seats with sweeps in LD2, LD8, and, of course, LD3. “I do think it is a new day in South Jersey," state-Senator Edward Durr (D-3), who defeated Sweeney, told InsiderNJ. “As Senator [Mike] Testa said, ‘We have built a red wall in 1, 2 and 3 and in the 8th. We are going to keep moving until we are able to turn New Jersey around. We’re a team here in South Jersey, and we’re going to work the Republican base. People say New Jersey is a blue state. I don’t think it ever was. I think stronger pockets of blue came out, and now we’re seeing stronger pockets of red coming out. We just took out the senate president. Maybe we can take out the speaker next time.”

Maybe we can take out the speaker next time.

To Durr's point, South Jersey overall went for Republican challenger Jack Ciattarelli over Coughlin's fellow Democrat Murphy: 428,171 to 359,403 votes.

Did Coughlin hear that and see it did it deepen his sense of concern?

His own election, a 26,529 vote win over nearest Republican challenger (19,337) represented his closest call ever (18,412 to 9,215 in 2019; 25,708 to 10,709 in 2017; 15,880 to 6,597 in 2015; 22,393 to 13,406 in 2013; 17,492 to 9,008 in 2011 and 22,226 to 17,555 in 2009).

In the lead-up to the 2021 election, NJ Building Trades President William “Bill” Mullen cautioned members about losing a sense of a core labor priority. “All we do is build,” Mullen said at the organization's annual convention in Atlantic City. “That’s it, fellas. We must not get involved in special interest campaigns or causes. That does not help our members and their families. That will only confuse our true purpose and dilute our influence. It is always about putting our members to work.

“We have worked with our legislative friends,” Mullen added. “Under the leadership of Steve Sweeney,

we have made New Jersey the leader in pro building trades laws. No one has what we have. We don’t need anymore legislation. Fellas, what we need is strong enforcement of our existing labor laws.”

Sweeney lost, a casualty, his allies insist, of a Democratic Party agenda that moved too far into those same special interest causes of the left decried by Mullen and championed by Murphy and North Jersey.

Middlesex now claims the most senior Building Trades representative in the Legislature: Assemblyman Joe Egan of New Brunswick; and of course, it claims the speaker.

An ally of Coughlin's likewise identified what he sees as the problem for Democrats in the aftermath of the 2021 election, when Ciattarelli - far exceeeding expectations in a state with one million more registered Democrats than Republicans - ran on a message of lowering property taxes by shifting extraordinary special education costs, restoring state aid to struggling suburban, shore area and rural schools, and redefining "local fair share” so no community funds less than 25 percent of its school operating budget or construction costs.

"We don't win these races by thousands of votes," said the Democratic Party source, speaking on condition of anonymity, referring to battleground legislative contests. "We win by hundreds of votes. There's a feeling out there that they [Democrats in the Legislature] went too far left. At the the end of the day, we lost six seats: 11, 2, and 3; and along the way picked one up in 16. If we had not gone so far to the left, the majority might be stronger. It's now now up to the speaker and incumbents to drive a middle of the road message. Coughlin can do it. The caucus is solidly behind him, which speaks well for his ability."

Perhaps, but with South Jersey's politically moderate voice stymied by Sweeney's loss and Murphy jockeying to get his name considered as a national progressive, and Sweeney's replacement, Senate President Nick Scutari (D-22) hailing from Democratic Party-friendly North Jersey, no less the state's chief purveyor of legalized pot - will Coughlin get lost in a northward-tilting whirlwind? Consider the fact that Coughlin and the MCDO have taken pains to foster a strong political relationship with Essex County (home to Chairman Jones), where Murphy - who ran for reelection joined by socialist Bernie Sanders in the closing days of the season - put up his best countywide numbers and won far more comfortably than he did in Middlesex: 132,520 to 45,542 - (For the record, Coughlin's home county put up 116,352 votes in the 2021 election for Murphy compared to 90,297 for Ciattarelli).

Will Coughlin attempt to appease the Building Trades as the organization searches for a new legislative home with Sweeney gone? Will he establish the builders' goal as a central organizing principle for his party, or fail to negotiate the political challenge of the party's fortunes hinging on Northern intention?

In a reply this week to some of those questions, Coughlin hit squarely the buzzword of affordability, perhaps signaling his preference to stay clear of those so-called special interest campaigns and causes identified by labor leader Mullen as a danger-zone in a state where the average New Jersey homeowner last year paid nearly $9,300 last year in property taxes.

“Since the beginning of my Speakership, the Assembly has always worked to advance an agenda that

supports our shared democratic priorities," Coughlin said. "Going into the new session, we will continue to make a difference across the many number of policy areas where we’ve already made tangible progress for New Jersey communities.

“Making our state more affordable for our over nine million residents and creating opportunities for our working, middle class families will be our top priority. Providing food and housing security, mental health, childcare, and small business resilience are cornerstone priorities for this session to help us achieve this goal.

“In this moment, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create transformative, lasting change," the speaker added. "As a leader I have always believed in letting the policy and its positive impact on communities speak for itself, always maintaining strong working relationships with my partners in state leadership and our colleagues across the aisle to create consensus around opportunities for legislative action.”

In a display of what that looks like - at least part of it - Coughlin last week put forward a 10-bill legislative effort expanding the State’s free breakfast and lunch meal program and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. The package, he noted, is the fourth set of measures sponsored by members of the General Assembly focused on strengthening food security.

“We’re in an ongoing fight against hunger in New Jersey,” the speaker said. “These bills mark the next step in the Assembly’s efforts to put food on the table of every New Jersey resident who needs the support, to ensure that no one goes hungry. They will help us to chart the course for a more affordable New Jersey. Our efforts will prove meaningful for our communities both now and into the future.”

The Assembly Agriculture and Food Security Committee will consider the bills on Monday.

But will Coughlin go farther in framing the issues that dog all New Jerseyans: high gas prices and food costs and a lack of job opportunities - in a coherent way, that the Democratic Party doesn't inevitably simultaneously undermine with its penchant for spending and dirty deals?

"From my perspective, the speaker is in an extraordinary position as a veteran principal in the legislature, with the ability to bridge gaps," said a source close to the Statehouse. "He has a good working relationship with Scutari and with Murphy. The speaker has a unique advantage. The senate president likes him. The governor likes him. He's in a unique position to drive the agenda."

What agenda?

Wreaking havoc on the residents of New Jersey while putting forward bills designed to look helpful, caring and substantial?

Veteran progressive activist and organizer Dr. Patricia Campos-Medina played a significant role in moving Coughlin to affirm drivers' licenses for non-citizens in New Jersey. She appreciates the pathway to a $15 minimum wage secured by the Murphy-Sweeney-Coughlin triumvirate during the governor's first term. But in the grand scheme of things, she hardly see the close-knit ties of the Trenton establishment as a virtue. She is also alert to the fact that the MCDO eliminated the state's lone Latina Mayor, Wilda Diaz of Perth Amboy, and that it was originally Coughlin, after all, in 2009, who defeated Diaz's assembly candidate to reassert the dominance of Woodbridge's party machinery.

"Murphy has a rhetoric of being progressive, which I would describe more as an anti-Christie agenda, using the energy of the left to ensure the old Christie forces don't become too strong," she told InsiderNJ. "The Democrats now - or many of them - in New Jersey are looking at the results of the 2021 elections and saying 'We need to go to the middle.' But if you look at the results for Murphy in a place like Hudson County, the Democratic base was not energized, because they did not believe Murphy had anything new to offer."

Murphy was progressive and anti-South Jersey bossism until he needed the organization lines in the party in time for reelection, then he made nice.

"You see it happening again with Democrats and the midterm elections," Campos-Medina said. "They are trying not to lose the midterms by being moderate, instead of fighting for what people need. You look at those votes in the Hudson neighborhoods, where Democrats, instead of talking about Donald Trump, should be getting healthcare done and family leave. In Murphy's case, he was saying 'I'm not Trump, and I did great in COVID.' But regular people are saying you didn’t do so great because a lot of people are still not working.

"There was nothing transformational," she added.

"In Coughlin's case, I think it would be refreshing for him to have his own economic agenda of working class issues," Campos-Medina said. "Sweeney came up his own policy issues. Coughlin, I think, has an opportunity to drive an economic policy agenda and to drive real policies on healthcare."

Perhaps state Senator Testa would like to see Coughlin undertake such an ambitious move, hampered as the speaker might find himself by the alliances in his own party that would doom his work by dragging it toward those causes Mullen condemned.

“Facebook messenger shows me people have reached an all-time level of frustration,” Testa told

InsiderNJ. He points out that he routinely, vociferously takes his case to Murphy, but “They tell me, ‘you’re not doing enough.’ People are messaging me, telling me all I’m doing is a floor speech or sending another letter.” Voters sent a message last year by nearly turning Murphy out of office. He won by the skin of his teeth, with the backing of northern counties like Essex and Hudson, even as the once-powerful Sweeney got the heave-ho down south, where Testa resides.

“I’m not so sure Democrats in North Jersey heard it or understood it,” the Vineland-based Republican said of Murphy’s three-percent squeak-out win.

Again, with Murphy looking to the White House and Scutari occupying a strongly Democratic district (or at least stronger than Coughlin's; Scutari beat his Republican challenger by 12,000 votes), does Coughlin have the adequate force of personality and the ability to project to define himself? New Jersey still has, on paper, regardless of the occupant, the strongest governorship; and the senate president, even a new one, has more governmental and political tools at his disposal than the speaker, including the powers of senatorial courtesy.

Sources look with interest at the ongoing legislative redistricting process, noting again the political power proximity of Middlesex and Essex, seeing the possibility of one of the two of them losing a senator and eating a loss that drops one lower than the other, finally pitting one county against the other. Middlesex and McCabe supposedly want Coughlin to be the next governor, while Jones favors U.S. Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D-11) from his home county. Can McCabe and Jones resolve that potential collision peacefully and avoid a fractured alliance that might resurrect the South (one county gets the governorship in 2025 and the other gets senate president, for example)? A Trenton source noted the apparent disconnect of Scutari and Coughlin from Jones' dumping of Sweeney from the commission, suggesting the key decisions won't come from the statehouse from the perimeter operators. "I found it incredible," said the source, "that both presiding officers were not in the loop." With moderates in his party running scared, but the power lords of Essex and Middlesex intractable and interconnected, can Coughlin gain

traction to meaningfully penetrate? As Murphy dims in New Jersey, will Middlesex - plotting its next statewide course - pivot to other counties for fear of getting dragged in too strongly an Essex direction, and will the machine be sufficient to carry Coughlin, who in the end may not require too great or deep or dramatic a voice anyway, as the disciplined creation of a growing Democratic county whose organization gained ground in 2021 while others lost, some catastrophically?

Both the right - Durr and Testa - and the left - Campos-Medina - caution about the hazards of his party's trajectory to date, as the political eyes of New Jersey turn to Coughlin and wonder, given the speaker's mild-mannered, gently vectoring past, if he can break out in a galvanizing, gambling direction, if the party will allow it or abide something more than merely the cannibalizing rituals of Sweeney versus Murphy spawned.