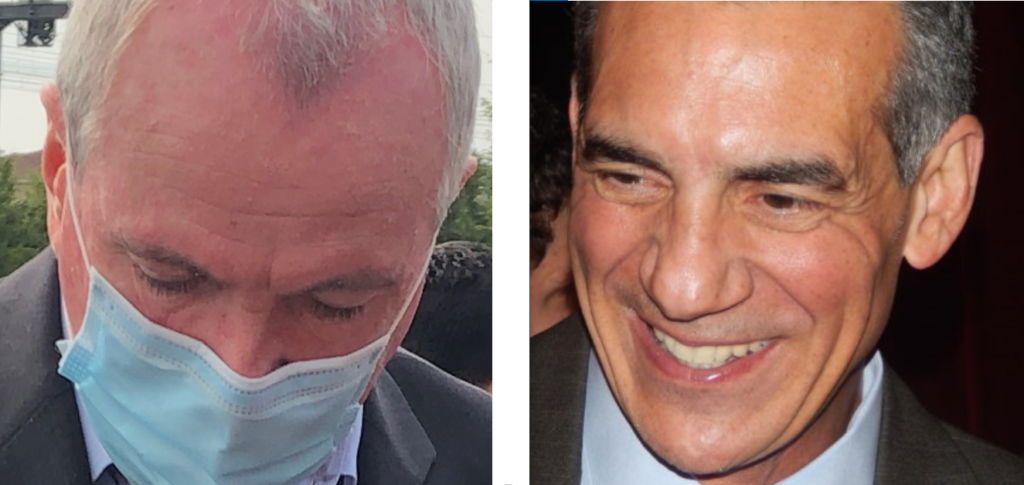

The State of Murphy v. Ciattarelli: Refighting Old Battles in front of an Exhausted Public

When Governor Phil Murphy spoke at the two-hour Asbury Park poolside speech-fest for the installation of the new Democratic State Chairman, LeRoy Jones, he said that he was going to run his campaign as though he was ten points behind until the polls closed on election day.

A Monmouth poll in May said that the Governor had a 57% approval rating with 35% disapproving, a fall of 14% from 2020 when the pandemic began. The pandemic, too, may well be the key to the entire gubernatorial election.

With businesses struggling to survive during lockdowns, failures on the state level to get money to those who needed it, whether as small business loans, unemployment funds, and other state services put New Jerseyans in a hard place. Many businesses, especially those in the dining and hospitality industries, simply could not survive. A haphazard and confusing application process often eluded the small businesses in need who were too busy trying to get by week to week than to untangle Trenton’s cumbersome machinery. All the while, infection rates soared, parents had to adjust to virtual learning for their children, and refrigerator trucks appeared in funeral home parking lots. Resistance to mask mandates and misinformation, propaganda, and politicization of vaccinations set New Jersey’s recovery process back, and the long hot summer of 2020, marked by protests for racial justice and gym guys kicking down doors to reopen their businesses, Murphy be damned, left a torrent of uncertainty and turmoil.

What Governor Murphy had going for him in 2020, politically, was that he was free of an election year and able to govern as he saw necessary and fit. This earned him the nickname “King Phil” from his detractors, mostly Republicans but certainly plenty of Democrats, who objected to his extension of emergency powers and endless issuance of executive orders.

It is not the place here to assess the full political impact of 2020, but as numbers began to decline, as vaccination efforts were generally successful, Governor Murphy was able to fight back against what Ciattarelli and Republicans had been picking at: interfering in business, interfering in schools, mandating masks, etc. With the approach of summer in 2021, it became a priority to get New Jersey open and back to business. The 2020 shore season was lost and another year might well seal the fates of those hardy seasonal businesses that did manage to survive. Fortunately for the governor, infection rates began declining and things rapidly began to reopen. The emergency was ended, the executive orders stopped, people could take off their masks if they got their shots. Those who didn’t get their shots and would likely never get vaccinated were no longer visually identifiable as non-compliant. New Jerseyans could breathe a sigh of relief and the Murphy-Ciattarelli race would start to take on more traditional forms once again.

That is, of course, until the Delta variant began to rear its ugly microscopic head.

With the COVID infection rates appearing on the Department of Health’s blue curve starting to show signs of a fourth wave, particularly among the unvaccinated, the pandemic will, once again, take center stage in the weeks and months to come leading up to Election Day.

Governor Murphy has been making his rounds and enjoys the advantage of the incumbency and a record to stand on. Historically, Democratic governors have not been re-elected since Governor Brendan Byrne 44 years ago. Republicans can and have made gains in a heavily Democratic state, but the nationalization of party politics in the Trump and post-Trump era has created an ideological minefield for both parties to contend with, but none more so than the GOP.

With former State Democratic Chairman John Currie, Phil Murphy had an unshakable ally. It remains to be seen the extent to which the Essex-county power base, embodied by the new Chairman LeRoy Jones, will play ball with the governor, but leading up to election day, the party leadership has rallied the rank and file behind the incumbent. Few Democrats see a Murphy alignment as a liability in the state, but the Republicans have stormier seas to navigate, and Jack Ciattarelli is faced with charting a navigable course to a safe port as well as captaining a crew which is far from wholly united.

Ciattarelli has put out the message that Murphy will be “one and done in Twenty-One” but has yet to communicate a clear and resonating message with the voters as to why he would be a better choice than Murphy. Simply not-being-the-other-guy may have been enough for many voters to cast their ballots for Joe Biden, but in New Jersey messaging is critical.

When InsiderNJ spoke to state-senate hopeful Dan Cruz, a Latino Republican running against Senator Oroho, he said he respected Ciattarelli but, at the time, was backing the more Trumpian Hirsh Singh. One of his key criticisms? He said that he did not see the GOP making efforts in the urban areas and that Democrats were winning the numbers game. Ciattarelli did make a recent stop in Elizabeth, knocking on doors and talking about Republican-safe issues like property taxes, but a city like Elizabeth remains solidly blue, even if residents complain about the status quo. In this case, Ciattarelli demonstrated he was willing to do what men like Cruz said the GOP would not, but the effect was, for insiders, fundamentally optical. The GOP doesn’t make strong GOTV efforts in urban areas because they need to focus their resources where it can be viable.

Ciattarelli continues to lack name recognition statewide, which will be problematic for the 37% of New Jersey voters who are unaffiliated. The Democrats have 38% of the voters while just over one-fifth of New Jerseyans are registered Republicans.

Singh had encouraged people in his mailers to “join the Republican Civil War”—obviously putting himself forward as the most Trump-like candidate while casting Ciattarelli as an “establishment” type. In other words, Ciattarelli actually held office and served the public in the Assembly, whereas Singh, who has never won office, would bring a fresh, outsider perspective.

Trump did not win New Jersey and Singh did not win the GOP primary, this much is evident. But it puts Ciattarelli in the unenviable position of trying to formulate a winning message and he is staring at a Gordian Knot. Unlike Alexander, Ciattarelli has no way of effectually and literally cutting through it (be it huge sums of campaign money, or more importantly, huge numbers of registered Republicans) and powering along to Election Day. Without a clear and easily communicated message, Ciattarelli’s campaign lacks the ability to focus on being much more than the Not Murphy. Moderate Republicans and conservative Democrats have respected the former Assemblyman as a public servant and also for being a voice of reason and civility in a time of shrill, incoherent chest thumping, tribalism, finger pointing, and name-calling that spread from DC to state capitals to town halls.

The likes of Phil Rizzo (styled “Jersey” Rizzo, to avoid association with the governor) and Hirsh Singh made no secret in exploiting Ciattarelli’s past criticisms of then-candidate Donald Trump. Ciattarelli himself rarely mentions the former president, which, to be fair, he should not have to, but this demonstrates the influence the former president has over the party, even in New Jersey. Attempting to win the base means shifting to the right, but Ciattarelli and the State GOP know the base isn’t enough. By asking for “wiggle room” from the base so that he can attempt to gain some of the crucial independent voters, Ciattarelli had to admit to abdicating some autonomy in his own campaign’s direction. To the outsider, then, Ciattarelli appears to be a reluctant right-winger.

It is a telling sign of the troubled times for the Republican Party when former Governor Christine Todd Whitman, the first female governor of New Jersey, endorsed Joe Biden and said the current GOP would be unrecognizable to her parents--she said it had become a cult of personality and lost sight of its core values. Former Lieutenant Governor Kim Guadagno joined the ranks of the unaffiliated voters as a result of political struggles closer to home in Monmouth county. She is also known to be less than a fan of Ciattarelli who ran against her in the 2017 primary.

With respect to the lieutenant governorship, Phil Murphy has Sheila Oliver, the second person to occupy that post, the second woman to do so, and the first African-American. As of this writing, Ciattarelli has yet to announce who would be his lieutenant governor candidate, a decision which has been put off for weeks. It is likely that whoever Ciattarelli picks would be female (and consequently continuing a New Jersey tradition of having women as lieutenant governors and lieutenant governor candidates) but speculation still swirls. Additionally, whoever Ciattarelli picks is unlikely to bring much star power if simply by virtue of how long it has been taking to choose a running mate.

Recent remarks by Ciattarelli about LGBTQ curricula being purged from schools, and that sixth graders would not be taught “sodomy,” was red meat for the Murphy campaign. They were quick to sink their teeth into the Republican while progressive groups like Garden State Equality lost no time in condemning Ciattarelli as dangerous and bigoted. But the move would score points with the Republican base and, perhaps, warm up some apathetic Trumpists who wished someone like Singh or Pastor Phil had won the nomination back in June.

So, where does this leave Ciattarelli? The best thing that can happen to his campaign would also be a catastrophic reversal for the health of New Jersey, and it seems that the course of events might be turning in that direction.

With the rising number of Delta-variant cases and the reduced efficacy of the vaccines against this particular strain, it is likely that further restrictions will need to be re-imposed to “crush the curve” as the governor said repeatedly. Masks are now being recommended for both vaccinated and unvaccinated people in indoor settings where there is a potential for high transmission. This is admittedly vague, and also an inevitable consequence of policy trying to catch up to data. During the height of the pandemic, the Republicans could make the case that individuals should choose how to handle their health, and that the government did not have the right to impose mask mandates on schools and businesses. Instead, the average person should be free to decide. When the governor rolled back most restrictions in the Spring, Murphy effectively took away the most coherent cudgel Ciattarelli had to swing with. With rising case numbers, especially among the unvaccinated who tend to be, although are not by any means universally, right-leaning, Ciattarelli could be given that weapon back once more.

Particularly dire for Murphy is that the will to return to the lockdowns is low among the business community. With the food industry especially suffering—one is hard-pressed to pass a diner, restaurant, or pizzeria without a Help Wanted sign in the window—to step back to 2020 could mean an inescapable fate. The Murphy campaign knows this, and the Ciattarelli campaign knows this as well.

As both the incumbent and the challenger spar over topics that would be conventionally safe for political debate, such as taxation, perhaps to the relief of both, the exceptionally non-partisan coronavirus will force the campaigns to realign and possibly refight old battles. In such an instance, Ciattarelli has the best chance to make his case and take some of the wind out of the governor’s sails. Depending on how the summer unfolds and the economic effects thereafter will determine whether or not Governor Murphy will be compelled to return to 2020 tactics in a 2021 battlefield. This time, however, without the shielding of a non-election year.