Steps to Strengthen Political Parties Remain Necessary Despite Deep-seated Distrust

When a major campaign finance bill was introduced during the previous legislative session in 2019, it contained provisions that would have financially strengthened party organizations in New Jersey.

The bill’s main purpose was to require independent spending committees that often operate with little or no disclosure- so-called “dark money” groups”- to abide by the same disclosure standards as candidates, parties and traditional political action committees.

The bill also contained a big boost for political party committees. It would have let them accept larger checks from political donors. Another section would have given county parties more influence over primary elections by freeing them to make unlimited transfers between their committees.

Both changes were dropped from the bill, which became law but was struck down by a federal judge because of other provisions he deemed unconstitutional.

ELEC continues to believe that disclosure by dark money groups and stronger political parties remain urgent priorities to help correct a major imbalance in the financing of New Jersey elections.

Party contribution limits have not been raised since 2005.

County-to-county transfers during primaries were banned as part of a 2004 reform package entitled “Restoring the Public Trust.”

Termed “wheeling,” transfers of money between county parties were viewed more as a way for wealthy donors to bypass contribution and spread their money around. It also was designed to limit the influence of county bosses over primaries.

During the past 15 years, however, party committees have become weaker because of these and other restrictions. At the same time, many special interest groups have opted to give less money to parties and instead spend more of their money independently on elections.

In 2005, the two state parties, four legislative leadership committees and 42 county parties together spent $38.7 million compared to just over $411,224 spent by independent groups. By 2017, independent group spending in New Jersey elections had increased 12,495 percent to $52.4 million.

During the same period, the collective spending of the “Big Six” and counties dropped 29 percent to $27.5 million.

As a result, independent groups in 2017 spent nearly twice as much as the 48 state and county party committees in New Jersey combined.

Spending on Gubernatorial and Legislative Elections

| Year | 2005 | 2017 | Change-% |

| Big Six | $19,667,905 | $13,348,131 | -32% |

| Counties | $19,009,467 | $14,114,921 | -26% |

| Total Party Committees | $38,677,372 | $27,463,052 | -29% |

| Independent Spending by Special Interests | $ 411,224 | $51,794,326 | 12,495% |

Additional data shows “dark money” also is growing in New Jersey federal elections. In the 2018 congressional election, independent groups spent 600 percent more than the parties, $50 million to $8.1 million, respectively.

While legitimate concerns about past abuses involving party bossism and corruption spurred efforts to rein in party officials, the fact remains that political parties are more transparent and accountable than many of the independent groups that are flourishing in recent elections.

Letting these increasingly powerful and often secretive entities dominate elections may create even more potential for corruption.

Just ask citizens of Ohio.

A scandal involving $60 million in dark money erupted in Ohio over a year ago with a major federal indictment. So far, it has led to the indictment and ouster of the state’s House Speaker (though he insists he is not guilty), a utility paying $230 million in fines, guilty pleas by two individuals involved in the alleged conspiracy, an 162-count complaint filed by the state’s campaign finance agency, and multiple reform bills.

New Jersey shouldn’t wait for such a scandal to enact its own reforms.

Unfortunately, distrust of political parties is deeply ingrained and dates back hundreds of years.

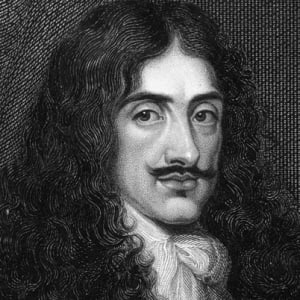

This skepticism toward political parties can perhaps be traced to 17th century England and the reign of King Charles II (pictured).

As was characteristic of the Stuart Era in England (1603-1689), a dispute emerged regarding the Anglican faith as the official religion of England.

Thomas Osborne, principal minister to King Charles II and Earl of Derby, identified the King as favoring the Anglican cause. Osborne and his followers were opposed by Anthony Ashley Cooper, the First Earl of Shaftesbury. As a versatile politician, the Earl of Shaftesbury cooperated with the effort to restore the monarchy, but at the same time favored religious toleration.

Stuart Era historians point to the factions that emerged over this religious divide- the (royal) “court” and the “country” – as the first modern examples of political parties.

Despite the emergence of party loyalty, individuals belonging to each faction refused to call themselves a party because they feared it might foster disunity. Thus skepticism toward political parties began soon after their birth.

These factional differences became all the more apparent during the reign of Queen Anne (1702-1714). Though Anne attempted to remain above party strife, Peter Ackroyd, author of ‘Revolution’ quotes her saying “if I should be so unfortunate as to fall into the hands of either (Tory on Whig parties), I shall look upon myself . . . to be in reality their slave.”

Ackroyd, referring to Queen Anne, comments: “She disliked and distrusted the violent partisans on both sides.”

A few years later, this distrust of parties was advanced by satirist Jonathan Swift in Gullivers Travels, published in 1726. Swift wrote: “They (Tory and Whig) will neither eat nor drink, nor talk with each other.”

This early reluctance about party, as with many traditions and customs, was adopted by Americans.

President George Washington in his farewell address to the nation in 1796 said “the common and continual mischief of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of wise people to discourage and restrain it.”

Upon writing to Thomas Jefferson he said: “I was no party man myself, and the first wish of my heart was, if parties did exist, to reconcile them.”

In 1838, at the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln said “party passion has helped us; but can do no more, it will in the future be our enemy.”

During the Progressive Era, reforms were enacted to blunt the influence of corrupt party machines. These reforms included government regulation of elections, voter registration, civil service, as well as constitutional amendments that gave women the vote and established direct election of U.S. Senators. Interestingly, the constitutional amendments had the support of the political parties of the day.

These reforms, while diminishing political parties, nevertheless were necessary at the time because they made parties more accountable and subject to statutory law. They did, however, help further instill skepticism toward parties in the public mind.

Further diminishment of political parties is no longer necessary and, in fact, may be counter-productive because of the emerging dominance of less accountable, less transparent “dark money” groups over the electoral process.

Political parties represent a broad coalition of people, organize government, and in this social media age of information overload they provide a guide to the individual voter who can look to the party label for help in understanding where candidates stand on the issues. On the other hand, independent groups provide no link to the candidates and therefore only contribute to overall confusion and lack of information on the part of voters.

Further, political parties disclose their financial activities, help to organize majorities in government and through so doing can bring compromise to an often polarized governmental process.

There are numerous other reasons why modern day political parties are good for government, not the least of which is that they get voters to the polls, something needed as voter turnout trends downward.

The Election Law Enforcement Commission has put forth the proposals for strengthening political parties and bringing transparency to independent groups involved in electioneering activity. It is hoped that the Legislature will consider the need to strengthen the parties as a way to further good government in New Jersey.

The recommendations include: remove parties from pay-to-play, include PACs under pay-to-play, disclosure by independent groups of contributions and expenditures in the context of electioneering, allow parties to participate in gubernatorial elections, increase contribution limits to parties, allow county to county transfers.

Jeff Brindle is the Executive Director of the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission.

The opinions presented here are his own and not necessarily those of the Commission.

“If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.” –Thomas Jefferson to Francis Hopkinson, 1789

George Washington said that political parties were incapable of providing good government. Read his Farewell Address