Theodora Lacey of Teaneck and the Ongoing Fight Against School Segregation

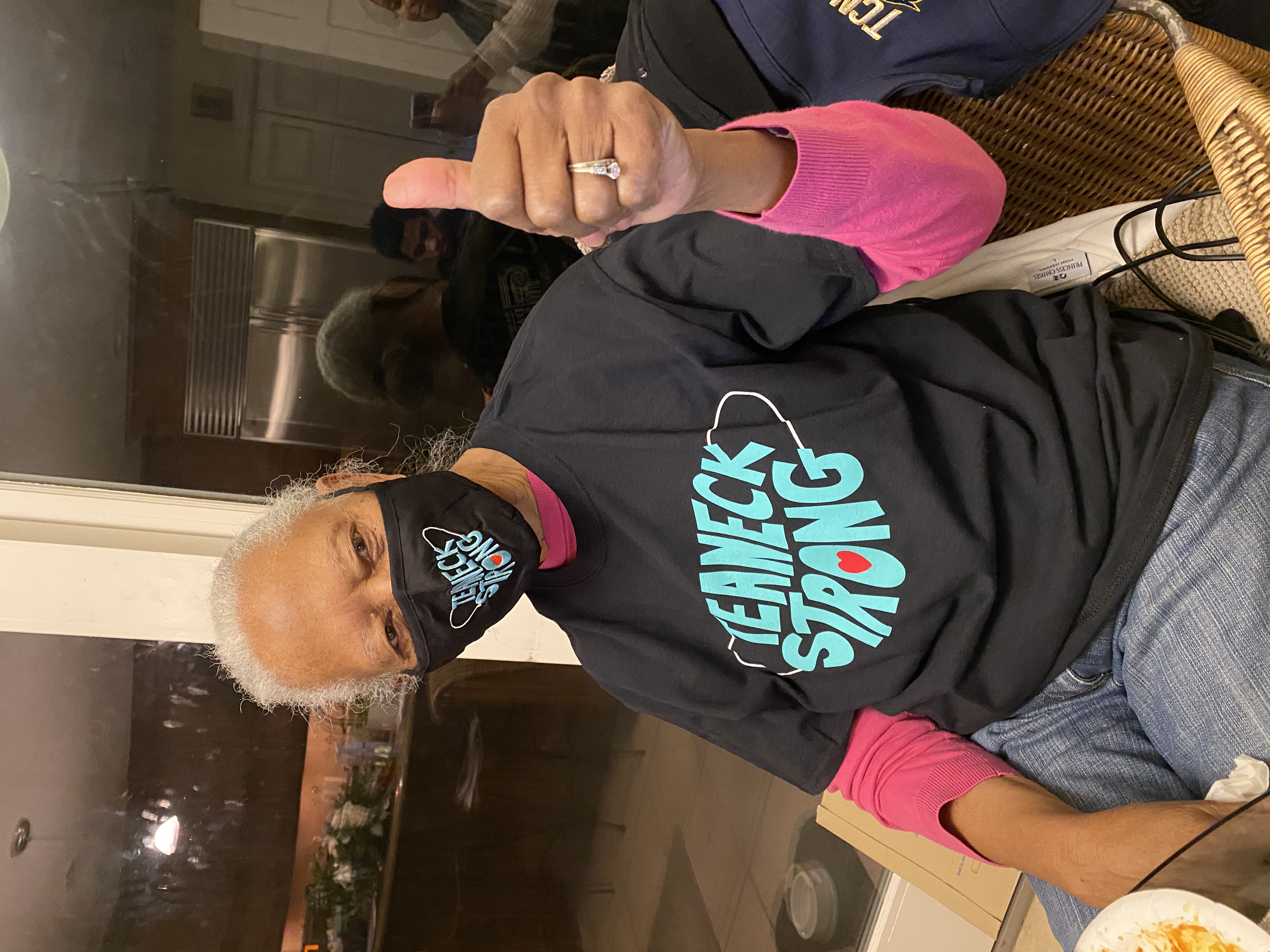

The Theodora Smiley Lacey School in Teaneck bears the name of the Civil Rights activist who has left an indelible mark on New Jersey. It’s the only school in the township that’s named after an African-American woman. The majority of educational facilities in this Bergen County community carry the name of white men.

Theodora Smiley Lacey is a retired Teaneck science teacher, who’s devoted decades of her life to fighting racial and social injustice. She and her late husband, Archie, are responsible for spearheading a 1960s movement that led to Teaneck’s school board voting to make Teaneck the first town in the United States to integrate its schools.

Most agree, a school should have been named after Mrs. Lacey much sooner than September of 2020. Still, the 89-year-old New Jersey resident remains humble and grateful.

“Completely overwhelmed because I never dreamed that I would be so honored,” Mrs. Lacey told me in a phone interview. “It’s quite an honor to be the first woman and African-American to have a school named after her.”

Mrs. Lacey’s contributions changed the lives of many Black and white children in Teaneck. The mother of four continues to share her wisdom with the nation, because frankly, it’s desperately needed during these divisive times.

Far From Over

New Jersey and many other states continue to grapple with systemic racism that’s unfairly affecting Black students. Nearly 67 years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case, New Jersey and four other blue states have gained the unfortunate distinction of having the most segregated school districts in the nation.

Teaneck’s schools have become more segregated over the years, mainly because white families are sending their children to private schools for religious reasons.

In addition, the far right and Republican lawmakers have seized an opportunity to take a concept called “critical race theory” and turn it into a blanket term to represent any kind of equity program that teaches students about racism and LGBTQ-inclusivity. Most school districts insist they don’t teach “critical race theory” but that hasn’t stopped conservative television networks from using the phrase to create more division in the country.

Those who know Mrs. Lacey say she’s a person who leads with love and compassion. Throughout her life, she’s fought school segregation, housing discrimination and voting rights violations. The Alabama native, though, found her calling and life’s mission fixing inequities in the educational system. Along the way, she’d meet Lawmakers like Democratic State Senator Loretta Weinberg in town, back then a young community activist determined to send her children to an integrated school.

“We were friends - till this day we still are,” Mrs. Lacey says of Senator Weinberg. “She was always actively involved. My favorite memory is her sitting in my kitchen and she would come and we would just talk, especially with my husband, who was very active in town. We would talk for hours about the conditions in the town. She (Senator Weinberg) was extremely active, and very positive, young and feisty.”

“Theodora Lacey and her husband are both icons here in Teaneck,” the 86-year-old Senator told me in a Zoom interview. “I met the Laceys through somebody who eventually became the mayor of Teaneck, Frank Hall — sitting around at this kitchen table at the Halls house is where we planned how we were going to win these fights.”

The two friends continue to tackle segregation in schools. In recent months, they held a Zoom meeting with Senator Weinberg’s granddaughter’s classmates in California to talk about their experiences. It’s why we thought looking back on how Teaneck voluntarily got its school district to integrate might shed some light on how educators today can combat school segregation.

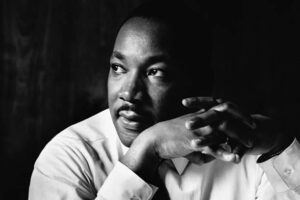

But to understand what Mrs. Lacey was able to accomplish in Teaneck, you have to look back on her life in the Deep South and her strong connections to Civil Rights Leader, The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King.

Meeting Dr. King

Mrs. Lacey grew up in the segregated South in Montgomery, Alabama. The southern city would become the center of the Civil Rights movement in the United States. Mrs. Lacey’s father served as the President of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church’s Board of Directors when it chose Dr. Martin Luther King as its new pastor.

“My father was instrumental in having Dr. King come to the church so I knew him as a family friend, he’d come to dinner and we would visit his home,” Mrs. Lacey recalls.

Senator Weinberg says she and other Teaneck activists were drawn to the Laceys not only because of their clear message and calm demeanors but also because of “this connection to the people we idolized.”

Mrs. Lacey’s push to integrate Teaneck’s school district, and later, to fight housing discrimination, wasn’t just shaped by her connection to Civil Rights icons but also by the way she was treated as a child and young adult in the segregated South.

“It was a constant, daily reminder that you were inferior,” Mrs. Lacey tells me. “I’ll tell you, it was because of our strong family and community relations that you were able to, I guess, swallow the indignities.

“Sometimes, I’d try to ride the bus and would be asked to put my money in the front of the bus, get off and go to the side, and sometimes the bus would leave before I could get to the side,” Mrs. Lacey remembers. “That happened to African-Americans all the time. Elderly people would sometimes have their arms caught in the bus and you would have to yell and scream for the bus driver to stop the bus from dragging the people. It was just cruel.

“There were drive-by shootings, people would drive in their trucks and throw Molotov cocktails into the homes of Black people, and there was violence at the churches so it was dangerous, as well.

“The text books (in Black schools) were books that were discarded from the white schools so that everything was inferior. Not only were the stores segregated, some stores you couldn’t try on clothes. I was pushed and just unable to try on clothes in department stores, all of those things, to make one feel inferior. It was just daily things that you couldn’t drink from the water fountain.

“I attempted to vote and I had to go back four times to register to vote and it was just my luck that the clerk accepted it. Prior to that, I would fill out the information and the clerk would take the sheets of information and dump it in the garbage can right in front of my face, not even looking at it.”

Mrs. Lacey says her parents constantly reminded her that racist laws couldn’t last forever and that the only way she could rise above the indignities was to get a solid education. She graduated from Alabama State College and got a job as a teacher in a local school.

“If you were not a professional, a teacher or a nurse or a physician in the African-American community, you did domestic work because you couldn’t work in the department stores, in the Capital buildings or hold any jobs outside of the African-American community,” Mrs. Lacey added.

Mrs. Lacey became involved in the Civil Rights movement when her mom’s close friend, Rosa Parks, got arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white person on a Montgomery bus.

“People had been arrested many times for sitting in the section where they weren’t supposed to sit, and asked to move,” Mrs. Lacey pointed out. “Mrs. Parks wasn’t the first so there had been many attempts. There was always ongoing efforts to get something done so when Mrs. Parks was arrested, it really ignited the community to take action. She was well-known and well-respected.”

Mrs. Parks’ arrest triggered the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Dr. King led the boycott and along with other civil rights activists urged African-Americans to stop riding buses until they were desegregated.

“When the boycott began, I was very much in attendance every night, strategizing to get things done,” Mrs. Lacey said.

Many of the activists involved with the Montgomery Bus Boycott were women, including Jo Ann Robinson.

“She was a college professor and president of a women’s political group,“ Mrs. Lacey explained. “We were very close friends so Montgomery is a relatively small town so it was easy to be involved in things.”

Hundreds of Blacks stopped riding Montgomery buses, starting in December of 1955. They needed rides to and from work. Mrs. Lacey knew she could help.

“I was able to get up in the morning and drive people to work and go to work,” She said, “and then in the evenings, come back sometimes and pick up people and attend the Martin Luther King Improvement Association Committee. It was busy, busy times.”

Mrs. Lacey’s writing skills also helped spread the word about the boycott. While she chuckles and likes to describe herself as a “gofer” during those early days, she was more like a press information officer.

“I was young at the time, I was able to type and I did a lot of the typing of the news releases and letters to the press concerning the boycott, and I was able to follow Dr. King as he traveled,” Mrs. Lacey recalls.

“We’re talking 1950s so there were no cell phones so we had to travel behind Dr. King to make sure he had reached his destination, and let his family know he was fine because he was often harassed.”

Mrs. Lacey’s courtship with her late husband began during the bus boycott. She says one of the more poignant and emotional moments for both of them was when Dr. King’s home was firebombed.

“I happened to have been in a meeting with Dr. King, again working, trying to keep the people off the buses and making sure we had cars and fuel to run the cars to pick up the people and take them back-and -forth,” Mrs. Lacey said.

“I remember the night Dr. King’s house was bombed and when word came to him that his house had been bombed, we jumped up to go to see what had happened to his wife and his daughter. He cautioned us to sit down, and he said no matter what has happened, the boycott will continue and it will continue peacefully.

“We finally got to his house, and of course, we see the neighbors, the people and the devastation of the bombing of his house. They had guns and bats, and all sorts of things ready to retaliate, and after checking on his wife, Dr. King said to the crowd, ‘put away your weapons, this is a non-violent movement.’”

The Montgomery Bus Boycott was hugely successful. It led to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that declared Montgomery's and Alabama's bus segregation laws were unconstitutional.

What Mrs. Lacey says she learned during those days was to set aside her anger and diligently fight for racial justice through non-violent means. Now, decades later, she’s having a difficult time watching the racism that continues to permeate the nation.

“I often ask what would Dr. King think of the situation that we’re in today?” Mrs. Lacey asks. “Someone had asked my late husband that question, and he said perhaps the better question would be, ‘what if Dr. King had not lived?’ So, I kind of lean on what I learned (from the) experience with Dr. King to help me through these times.”

The Centralized Sixth Grade Plan

The Laceys got married in 1957 and traveled through Alabama, focusing on voter registration, documenting violations. When Mr. Lacey was offered a job as a professor at Hunter College, the couple and their children moved to New York. They kept in touch with Dr. King, and Mrs. Lacey fondly recalls one of her last meetings up North with the Civil Rights leader.

“We talked about the South and we assured him there were plenty of things that needed to be done in the North, and we laughed about it, and he agreed,” Mrs. Lacey remembered. “He was very close to us and to our family.”

While living in New York, the Laceys visited a friend across the river in Teaneck and fell in love with the township. They bought a home in Teaneck and moved into it back in 1961.

“When we moved to Teaneck, we were very pleased to come to a town that was known as an outstanding educational center with the opportunity for children to develop and grow, and it had one of the best school systems in the state so we were very pleased,” Mrs. Lacey said. “But we knew there were problems up North. Because of redlining, because of discrimination, all of the Northeast section of Teaneck was only for Blacks to buy homes.”

The Laceys neighbors, though, were white. Several moved out of the neighborhood when they moved in, and a male neighbor who stayed, terrorized them.

“It was an elderly couple next door to us on the corner,” Mrs. Lacey said. “When our children would go outside with their tricycles, he would come and sit on his stoop with his shotgun. He did stop because my husband made it clear he would not tolerate that. There was some senility involved but it was frightening.”

Despite the scare, Theodora and Archie didn’t waste any time getting involved in their kids’ education.

“We knew the history of schools in the North and when they became increasingly Black, something happened, the schools began to deteriorate,” she pointed out. “Teachers left and resources seemed to disappear. After being here in Teaneck about three years, we began to notice the local neighborhood school was becoming increasingly African-American.

“We wanted our children to learn to live with people who are different (from) them. We wanted them to be in an integrated setting and so I was very active in the PTA.”

The Laceys set up a meeting with then Schools Superintendent Harvey Scribner. They would discover quickly the Superintendent, originally from Vermont, would become a staunch ally.

“We shared with the superintendent and the board our concern about the white flight that was developing in this area as Blacks moved in,” Mrs. Lacey said, “whites were leaving.”

In 1962, the Laceys helped start the “Volunteer Program” in the Teaneck school district. It was an innovative proposal at the time.

“You could volunteer your children out of your community to any other school in the district,” Mrs. Lacey said. “But that wasn’t successful because while we were able to get 13 families in the African-American community to send their kids to other schools throughout the town, only one white family registered.”

For the Laceys, though, failure was not an option. They helped spearhead another campaign, dubbed the “Centralized Sixth Grade Plan.” Under the proposal, all sixth graders in the district would be bused to the Bryant School, which was in their neighborhood. The move would not place the onus on Black children to be bused to the school. Instead, students living in mostly white areas would come to Bryant.

New Jersey State Senator Loretta Weinberg worked as a volunteer activist during that campaign. The Senator and her husband had just moved to Teaneck with their children.

“I was really proud at the time, although I played a secondary role,” Senator Weinberg said. “The Central Sixth took place right after we moved here. So, that was my first campaign. You know, I crawled up and down stairs and did door hangers.

The Senator’s daughter, Francine Weinberg Graff says “it was boots on the ground activism.”

The campaign was a huge success, and in 1964, the Teaneck School Board voted to adopt the “Central Sixth Grade Plan” and in doing so became the first town in the U.S. to voluntarily integrate its school system.

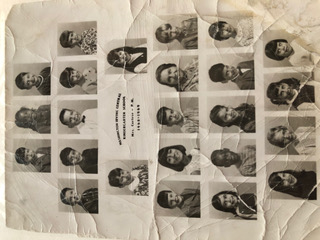

But the Laceys, Weinberg and others involved in the Teaneck school integration movement wanted more and persistence paid off. In 1965, the school board approved district-wide integration. Mrs. Lacey says the centralized sixth grade school flourished and in 1968 a centralized kindergarten school completed the mission.

“By Central Kindergarten, I was more of an organizer and I met the Laceys and other leaders and it was all about having the right school board members,” the Senator said. “To me, the real noted history of Teaneck ... we elected people who realized it was not appropriate to just put the responsibility of busing on a particular group of children, and out of that we created the Central Kindergarten so that all kids were bused.”

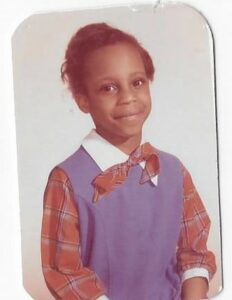

The Senator’s daughter, Francine, and twins Lisa Robinson and Lori Williams were part of the 1968 integrated kindergarten school. Francine Weinberg Graff rode the bus to school on her first day of kindergarten.

“When Kamala Harris took on Biden in that original primary debate when she explained, ‘I was the little girl at the bus stop,’ I wrote an op-ed piece that Francine Weinberg was also a little girl at that bus stop,” Senator Weinberg added.

Francine Weinberg’s friends and classmates, though, twins Lisa Robinson and Lori Williams, walked to school on their first day of kindergarten.

“I just remember my mother holding our hands, you know, one on each side, and crossing the street, always reminding us to keep our heads up, be proud you’re Black,” said Robinson, now an associate church minister with a Ed.D in social justice. “

Both Lisa and her sister remember their first day of kindergarten feeling uneventful. There were no protestors, police escorts or major TV cameras. They say it just felt normal. As Senator Weinberg puts it, “We just had Mr. Anderson, the crossing guard.”

“As far as being in class, we had people from all kinds of different backgrounds,” said Lori Williams, now an attorney working abroad. “We learned to be around people who didn’t look like us. As I get older, I could move around in different circles. Everybody has their biases, and I don’t start in a place that ‘I don’t like you automatically just because of the color of your skin.’ I really give people the opportunity to show me who they are without judgement right off the bat.”

“As far as being in class, we had people from all kinds of different backgrounds,” said Lori Williams, now an attorney working abroad. “We learned to be around people who didn’t look like us. As I get older, I could move around in different circles. Everybody has their biases, and I don’t start in a place that ‘I don’t like you automatically just because of the color of your skin.’ I really give people the opportunity to show me who they are without judgement right off the bat.”

Both sisters say they have both faced discrimination outside of Teaneck but attribute their strength in dealing with injustice to their days growing up in the township. They say it wasn’t always easy in Teaneck, either.

“Where Lori and I lived, we went up the street past the kindergarten school to the high school, and you made a turn and went through the door — that’s where a lot of African-Americans entered because we lived on that side of the school,” Robinson said.

school to the high school, and you made a turn and went through the door — that’s where a lot of African-Americans entered because we lived on that side of the school,” Robinson said.

“And this infamous ‘Black door’ and ‘white door,’ and the fact the school didn’t even acknowledge it,” Francine Weinberg Graff added.

Like her sister, Robinson has traveled around the world for work and studied how people of different backgrounds interact. The Reverend says integrating school children at a young age is the key to fighting racism. Now living in Charleston and having a daughter of her own, she believes conversations are the key to bringing people together.

“Even as I went through my doctoral program of social justice training, you get a group of people in a room, and get them to speak honestly, and you hear the conversation, and see their brains working and wanting change,” Robinson added. “When you don’t have that dialogue … you can’t talk about these things but we need to … in churches, classes and at community groups.”

What if there were programs within all districts that would allow students to travel outside their towns and have conversations with other students? As Robinson points out, solutions are complicated.

“I think what’s going on now when people are segregated, they don’t get that foundation,” Robinson said. “My friends are white, Black, Latino and Asian.

“I look at Teaneck and the schools being predominantly African-American, which is a huge difference from when we were there, and even some of the students saying they feel it when they walk around town so you can’t separate the school system from the town because that’s where the experiences are really felt.

“When you see what we have all of these schools that were integrated starting to be segregated again, it’s just different levels of racism and separation and discrimination and I think one of the things that was said, we can’t always legislate peoples’ hearts so it has to change from the inside for people to want to change.”

'The Problems are Still the Same'

Mrs. Lacey and Senator Weinberg both agree legislating school integration doesn’t always work. Mrs. Lacey says creating stand out schools in Teaneck or other New Jersey towns may be the answer to bringing children of all backgrounds together.

“What if tomorrow, Teaneck High would become the best science technology or computer school in the district and you’d have a flood of white people coming back into the district?” Mrs. Lacey said. “Education seems to generate a lot of attitudes and behaviors, and so people run, and they fear things because they just don’t know. It’s out of ignorance but if someone can identify Teaneck as the best school in the district or the best journalism or the best science and technology school, then people wouldn’t run from that.”

Specialty schools like that exist in Hudson and Union Counties but they’re not free. Mrs. Lacey says New Jersey, which bases public school funding on property taxes, needs more of these technical educational facilities across all school districts.

“It kind of boils down to economics,” Mrs. Lacey added. “When we begin to get more equity in those areas then we can begin to solve our problems but we’re not because you don’t have an equal number of African- Americans in executive positions and economically able to afford housing in certain areas,” she said.

“I had a lot of friends in middle school, who moved out way into the suburbs,” Francine Weinberg Graff recalls of her school days in Teaneck. “Some are still angry at their parents for doing it.”

Senator Loretta Weinberg is retiring in January and says she’s been thinking about the state of school affairs in New Jersey a lot these days.

“Isn’t this where I walked in and now I am walking out, at least retiring from elected life, and the problems are still the same,” the Senator told me, nodding her head in dismay as we spoke during our Zoom meeting. “We’ve certainly made progress but even in Teaneck we haven’t, not because of ill-will on anybody’s part but because of the changing demographics here as you’re finding a more conservative, religious community who are finding the infrastructure they need in terms of synagogues and restaurants.

“There are obviously younger families moving in from that demographic and they don’t send their children to public school. I wouldn’t want to pass any rules or laws or regulations, but at the same level, I feel like I am walking out at the same level I came in in terms of this issue.”

Both Senator Weinberg and Mrs. Lacey say they plan on working together to continue to share their experiences.

“It’s the economy, it’s the educational opportunity, it’s teaching people to learn for themselves,” Mrs. Lacey said, “but I do have hope … young people are not growing up with the same kinds of inhibitions that were imposed upon older people so I think that they will be coming from a different point of view and I am hopeful that they are going to help save us.”

Two graduate students at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison are trying to do just that. Through research, they’re trying to figure out the deep causes of school segregation in the modern era. The Latino Action Network’s also filed a lawsuit against the state of New Jersey. The organization says New Jersey schools are segregated, and that the Garden state provides separate and unequal schools to minority students and that is a violation of their Constitutional rights. All of those topics, the subject of our next story.