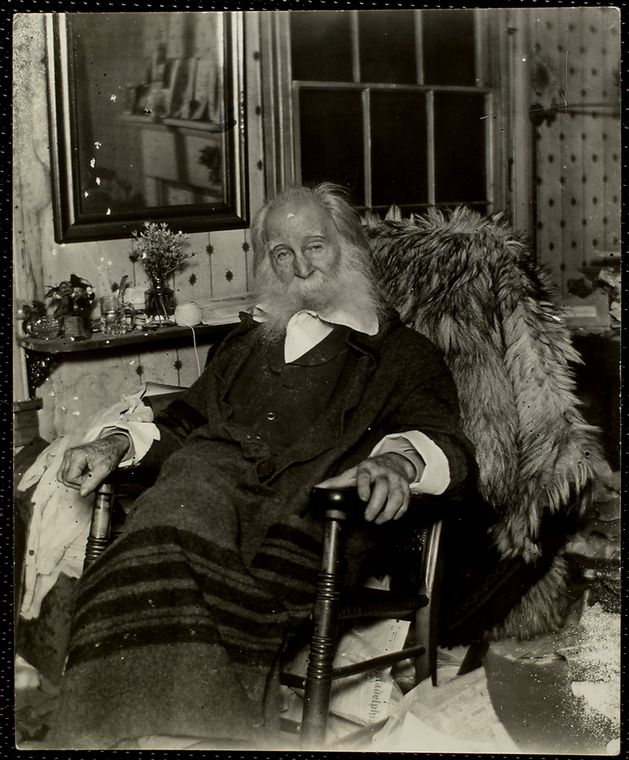

Walt Whitman’s Camden 2021

“I can conceive of not better service…than boldly exposing the weakness, liabilities and infinite corruptions of democracy,” wrote Walt Whitman, poet, journalist and one of the City of Camden’s most historically significant residents who died in 1892.

Whitman moved to Camden to his brother’s home after a debilitating stroke in 1873. Considered one of our nation’s most gifted writers, he was an ardent abolitionist and supporter of women’s rights. His optimism on the prospects for a more inclusive American democracy were at odds with his assertions about the superiority of the white race, which continue to spark controversy.

“The charge of racism was particularly fraught because it was levied against Walt Whitman, the poet who in Leaves of Grass sang of American democracy as a project of radical inclusion, the poet who wrote about tending to the runaway slave, the poet who looked upon the enslaved person on the auction block and saw in them their generations of descendants, the poet who declared that the enslaved were the equal of those who enslaved them,” writes Lavelle Porter, is his essay “Should Walt Whitman be Cancelled”.

Whatever Whitman’s views on race were, it’s worth reflecting on just how democracy has worked out 21 years into the 21st century for his adopted city. Since the 1890’s, Camden has become a majority minority city and consistently ranks as one of the poorest communities with some of the most glaring health disparities in the nation.

In 1950, Camden had a population of 124,555, ranking it as the U.S. 86th largest city. Today, it’s close to 74,000, making it the 487th largest. For decades, through our tax policy, the U.S. incentivized corporations to shift manufacturing overseas. No matter who controlled the White House or Congress, our elected leaders served the interests of the donor class and much of urban America was hallowed out in the process.

Today in Camden, according to the U.S. Census, just 5.8 percent of the population is white, 41.4 percent Black and 51 percent Hispanic or Latino. In over 45 percent of the households a language other than English and just 63.9 percent of the households have a broadband internet account.

Over 36 percent of the population lives below the poverty line, compared to 9.2 percent for New Jersey as a whole. But that’s only part of the story. According to the United Way’s ALICE project, which tracks families living above the official poverty rate, but unable to make ends meet, over three-quarters of the city is struggling economically.

According to the NYU School of Medicine’s Department of Medicine City Health Dashboard, which collects health data on 500 of the country’s largest cities, Camden City residents’ average life expectancy at 73, six years shorter than the other cities NYU tracked. In at least one zip code in Camden, the average life expectancy was more than decade shorter than the rest of the average in the surveyed cities.

According to the New Jersey Department of Health, Camden’s infant mortality rate is 7.3 per 1,000 live births, compared to 4.3 in the rest of the state. “The infant mortality rate in New Jersey has been generally decreasing since the early 1900s,” according to NJDOH. “However, the rate varies widely across the state and by several maternal and infant characteristics. The rate among Blacks is more than triple the rate among Whites and double the rate among Hispanics.”

In New Jersey, perhaps no other city offers such a clear illustration of how systemic racism, massive wealth inequality, and poor health outcomes all intersect. Consider NJ Spotlight’s May 28 report that only 31 percent of Camden has gotten their COVID vaccination, while 80 percent of the eligible residents of neighboring Haddonfield have gotten their shot.

The Democratic Party and its county organization has dominated Camden’s politics for decades. In 1860, Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican to be elected president, lost Camden County and the popular vote in New Jersey. (Lincoln, did manage, however, to win 4 out of New Jersey’s 7 electors.)

Not surprisingly, with one party rule so concretely established, the city has suffered from multiple corruption scandals going back decades. Looking at election results going back twenty years, it’s not uncommon in a primary election, which in a mono-party city is the election, for less than ten percent of the eligible voters to turn out.

“The ills of this desperate city deepened today with the indictment of its mayor, Milton Milan, on 19 charges of corruption, ranging from laundering drug money and taking bribes from organized crime leaders to stealing his own computer, collecting the insurance and then selling it to a naive office volunteer for three times its worth,” reported the New York Times in 2000. “Mr. Milan, who was elected in 1997, is the third Camden mayor to be indicted in the last 20 years.”

Arnold B. Webster, Milan’s predecessor pled guilty to federal wire fraud charges in 1998. Back in 1981, Mayor Angelo J. Errichetti, was convicted on corruption charges and went to federal prison in 1981.

In 2006, a Camden City Councilman Ali Sloan El, resigned his office before he pled guilty to federal corruption charges. In 2008, former State Senator Wayne Bryant, the former chair of the Senate Budget Committee was convicted on corruption charges.

For a generation Camden politics, indeed South Jersey entire Democratic Party’s landscape has been dominated by George Norcross III, South Jersey’s unelected Democratic boss and his family.

Norcross sits atop a sprawling nexus of insurance, health care and philanthropic enterprises and historically has been one of those wealthy Democratic National Committee members who, despite some progressive rule changes post 2016, gets to have an oversized role in picking his party’s presidential nominee.

He has taken a leading role in the revitalization for all things in the Camden, taking aim at reforming public education and public safety. While his civic engagement has burnished a national reputation as a philanthropist, WNYC and ProPublica reported that of the $1.6 billion in controversial New Jersey Economic Development grants given out to Camden, Norcross and businesses connected with his family were beneficiaries of $1.1 billion of that state stimulus.

His boss-like hold on political power ties back to his family, his material means, decades of philanthropy, and a track record for making investments in Camden that have produced some results in terms of improved school performance and crime reduction while maintaining a near feudal control over local politics even though he doesn’t hold elected public office himself.

In July, WNYC reported the Murphy administration had “put a freeze on $578 million worth of tax breaks” to a dozen companies including to Norcross linked firms that had been awarded the grants from the New Jersey Economic Development Authority under Christie.

According to the public radio station “of the 12 companies, five are connected to Norcross and represent the vast majority of the dollars — $540 million of the $578 million total — that have been frozen by the EDA.”

WNYC quoted Jim Walden, lead investigator for the Governor’s Task Force on EDA Tax Incentives, that there had been criminal referrals of several companies to law enforcement but “he didn’t specify which ones or what possible charges the companies may face. He said the investigations are still active.”

The freeze came after the Murphy administration followed up on a NJ State Comptroller’s audit of the EDA’s tax incentive programs that “revealed startling deficiencies in monitoring and oversight,” according to a 2019 press release put out by the Governor’s office. “The audit released earlier this month unfortunately validated my long-standing concerns that New Jersey’s tax incentive programs gave out billions of dollars in tax breaks but failed to deliver the promised economic benefits,” Murphy said in the statement at the time.

For Vida Neil, a long time Camden City resident, political activist, and former municipal employee, the NJ EDA scandal is just the latest in a long saga of a self-dealing political power structure in the form of a Democratic Party machine dominated by outside interests that appear to get wealthier as her city struggles for the basics. “Our streets are still atrocious,” Neil said. “We still got all this blight, homelessness, and all that Camden still is.

“Murphy had the lawyers on it, and we had the EDA hearings and then Murphy realized he needed Norcross and all of the sudden it stopped,” she said. “It’s hard to beat the big money. The only way you can do that is if all the citizens come together.”

Wonder what Walt Whitman would say?

Leave a Reply