When Sandman and Maraziti Fought Rodino over Impeachment

Impeachments of a president are momentous occasions in United States history, political upheavals which challenge the very core precepts of democracy and freely elected government. Accusing a President chosen by the people of criminal conduct sufficiently serious that removal from office in defiance of the popular will is the sole remedy is an act that severely tests the consciences and principles of those who bear the responsibility and the burden of forcing the chief executive of the nation and the leader of the free world to step down.

It is not a constitutional prerogative exercised lightly or frequently. There have only been three in the 243 years since the nation was founded while we currently stand on the cusp of a fourth. They attract outsized media attention, mesmerize the nation and, in the communications revolution buffeting daily life today, produce analyses, predictions and commentary --- insightful or ill-informed --- that achieve global knowledge in minutes.

History’s first occurred in 1868 with the attempted removal from office of President Andrew Johnson, the country’s 17th chief executive.

One hundred six years elapsed and 20 presidents had served until the second when charges of obstruction of justice and abuse of power were brought against Richard Nixon in 1974 but never voted on in the House.

24 years and six presidents later, Bill Clinton faced impeachment in 1998 on charges of obstruction of justice and falsely testifying to a grand jury.

Should the House approve articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump, only 21 years and three presidents later will have elapsed since then.

Johnson and Clinton were acquitted in Senate trials while Nixon resigned the office when it became clear that his support in the Senate had crumbled and he would be convicted.

While the outcomes are all duly recorded by history, the central role played by members of

Congress from New Jersey in the Nixon impeachment often receives only a passing mention or is overlooked altogether.

Granted, the process occurred 45 years ago, long before the internet and social media defined and controlled the political narrative. The dusts of time and the coming of age of a new generation not yet born have obscured all but the most vivid recollections, leaving only the end result --- criminal charges against the president--- lodged in the public consciousness.

The House Judiciary Committee which debated and considered the articles of impeachment against Nixon was chaired by U. S. Rep. Peter Rodino of Newark, while two of the president’s most vocal defenders on the committee were Republican Reps. Charles Sandman of Cape May County and Joseph Maraziti of Morris County.

There was a significant degree of consternation expressed over Rodino’s leadership role by some Democrats who felt he was inadequate to take on the historic task of what is arguably Congress’ most compelling exercise of its Constitutional authority.

Rodino was, they believed, the epitome of an urban machine pol, occupying a secure seat in Congress and immune from any serious political challenge as long as he remained faithful to the machine leadership.

They feared he would wither under the relentless glare of media scrutiny and intense political pressures.

He had not particularly distinguished himself during his years in the House, often joking that his most significant accomplishment was enactment of his legislation to designate Columbus Day a national holiday.

He rose to the committee leader post only because he was second in seniority when the incumbent chairman was defeated in a primary challenge.

In his 1976 book “How The Good Guys Finally Won,” Pulitzer Prize winning reporter and author Jimmy Breslin wrote that Rodino himself confessed some inner doubts, musing: “If fate had been looking for one of the powerhouses of Congress, it wouldn’t have picked me.”

Breslin wrote also that House Speaker Tip O’Neill quickly doused any effort to replace Rodino, telling his colleagues: “When the rest of us are all forgotten, Pete is the guy who is going to be in history.”

Upon learning that Rodino would lead the committee deliberations, Nixon, who frequently vented his

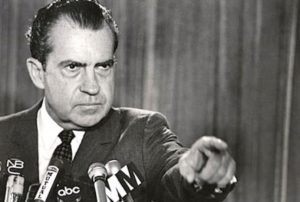

[caption id="attachment_17294" align="alignleft" width="300"] Nixon[/caption]

Nixon[/caption]

anger and contempt in deeply ugly bigoted terms did so once more and was captured on his own office taping system: “The Italians are not like us…they smell different…they look different…they act different. The trouble is you can’t find one that is honest.”

Rodino not only rose to the occasion, he responded brilliantly to the challenge as the committee approved three articles of impeachment. The diminutive machine pol from Newark had brought about the beginning of the end for Nixon, masterfully leading a committee whose work was so thorough, so convincing, so unassailable that Republican Senators who may have been disposed toward Nixon concluded that further resistance was futile.

While Maraziti and Sandman were in the committee minority, they mounted a ringing defense of the president.

According to news accounts, Maraziti warned committee Democrats: “You have weakened the hand of the President and the 220 million people he represents.”

Sandman strove unsuccessfully to amend the impeachment articles to soften their impact and persuade his colleagues and wavering Senators that the offenses alleged were not sufficiently egregious as to warrant Nixon’s removal. He abandoned the effort when it became clear the committee majority was united in its opposition.

There is a personal connection between me and the three New Jersey Congressmen who played such prominent roles in the Nixon impeachment drama.

I met Rodino in 1966 when I joined the staff of Rep. Peter H. B. Frelinghuysen, a Republican who represented Morris and Somerset counties.

Rodino and his Essex County colleague, Rep. Joseph Minish, often took morning coffee at a table in the cafeteria of the Rayburn House Office Building and one morning Rodino invited me to join them, the start of something not quite a ritual, but a fairly frequent and thoroughly enjoyable start to the day.

Rodino recounted tales of Essex County politics, commenting on the colorful personalities involved and recalling the innovative and amusing methods employed to punish wrongdoers, reward the faithful, and assure a smoothly functioning organization.

It was an education in practical politics not attainable elsewhere.

Prior to joining Frelinghuysen’s Washington, D.C., staff, I was a reporter assigned to the Northwest New Jersey bureau of the Newark News headquartered in Morristown. I met and covered Maraziti, then a member of the New Jersey Senate and when Sandman, also a State Senator, ran for governor in 1965, I covered his campaign swings through the Morris County region and came to know him rather well.

Both were gregarious, enjoyable individuals with whom to share time and company and both relished the tumult and turmoil of New Jersey politics.

Sandman and Maraziti were defeated in their re-election bids in 1974, attributable in large measure to the Watergate scandal while Rodino closed a 40-year career in Congress when he retired in 1989.

By the time of the Nixon impeachment, I had left Capitol Hill and returned to New Jersey to pursue a different career path, although one still involving politics.

As the current inquiry into whether Trump has committed impeachable offenses proceeds, I am struck by the differences in tone and context between it and the Nixon hearings.

While the partisan overtones were certainly in force in 1974, there existed a civility and respect lacking in today’s environment. As committee chairman Rodino was scrupulously even-handed. Committee Republicans were accorded the same rights of questioning witnesses and entering materials into the record as the Democratic majority members.

Rancor, bitterness and personal animosity seemingly rule in the poisonous atmosphere of today. Destruction rather than accepting the solemnity of constitutional obligations has become an end in itself.

Forty-five years ago, the Democratic machine pol from Newark, and the Republican representatives from suburbia and South Jersey proved the system --- while adversarial --- could work as the founders intended without dividing the nation and creating a polarization that will not soon be healed.

Carl Golden is a senior contributing analyst with the William J. Hughes Center for Public Policy at Stockton University.